It had taken the better part of a decade, but Reed Hastings was finally ready to unveil the device he thought would upend the entertainment industry. The gadget looked as unassuming as the original iPod—a sleek black box, about the size of a paperback novel, with a few jacks in back—and Hastings, CEO of Netflix, believed its impact would be just as massive. Called the Netflix Player, it would allow most of his company's regular DVD-by-mail subscribers to stream unlimited movies and TV shows from Netflix's library directly to their television—at no extra charge.

The potential was enormous: Although Netflix initially could offer only about 10,000 titles, Hastings planned to one day deliver the entire recorded output of Hollywood, instantly and in high definition, to any screen, anywhere. Like many tech romantics, he had harbored visions of using the Internet to rout around cable companies and network programmers for years. Even back when he formed Netflix in 1997, Hastings predicted a day when he would deliver video over the Net rather than through the mail. (There was a reason he called the company Netflix and not, say, DVDs by Mail.) Now, in mid-December 2007, the launch of the player was just weeks away. Promotional ads were being shot, and internal beta testers were thrilled.

But Hastings wasn't celebrating. Instead, he felt queasy. For weeks, he had tried to ignore the nagging doubts he had about the Netflix Player. Consumers' living rooms were already full of gadgets—from DVD players to set-top boxes. Was a dedicated Netflix device really the best way to bring about his video-on-demand revolution? So on a Friday morning, he asked the six members of his senior management team to meet him in the amphitheater in Netflix's Los Gatos offices, near San Jose. He leaned up against the stage and asked the unthinkable: Should he kill the player?

Three days later, at an all-company meeting in the same amphitheater, Hastings announced that there would be no Netflix Player. Instead, he would spin off the device, letting developer Anthony Wood take the technology and his 19-person team to a small company Wood had founded years earlier called Roku. But Netflix, which had already begun streaming movies to users' PCs, was hardly giving up on the idea of streaming them to televisions as well. Instead, the company would take a more stealthy—and potentially even more ambitious—approach. Rather than design its own product, it would embed its streaming-video service into existing devices: TVs, DVD players, game consoles, laptops, even smartphones. Netflix wouldn't be a hardware company; it would be a services firm. The crowd was stunned. In half an hour, Hastings had completely reinvented Netflix's strategy.

Today, nearly 3 million users access Netflix's instant streaming service, watching an estimated 5 million movies and TV shows every week on their PCs or living room sets. They get it through Roku's player, which was successfully launched in May 2008. (The Roku now also offers more than 45,000 movies and TV shows on demand through Amazon.com and, since August, live and archived Major League Baseball games.) They get it through their Xbox 360s—Microsoft added Netflix to its Xbox Live service last fall. They get it through LG and Samsung Blu-ray players. They get it through their TiVos and new flatscreen TVs. By the end of 2009, nearly 10 million Netflix-equipped gadgets will be hanging on walls and sitting in entertainment centers. And Hastings says this is just the beginning: "It's possible that within a few years, nearly all Internet-connected consumer electronics devices will include Netflix."

And the devices won't just be streaming remaindered basic-cable or art-house fare: Already, Netflix customers can call up just about any episode of SpongeBob SquarePants, The IT Crowd, or Lost whenever they like. They can watch recent releases like WALL-E and Pineapple Express. In other words, they can get unlimited access to the kinds of programming that previously required a cable subscription. (One visitor to the Netflix blog was particularly pleased to see that they could stream old episodes of Dora the Explorer: "We couldn't cancel cable until more kids' shows were available to watch instantly. Thanks for saving us another $400/year.") Netflix has taken the boldest step yet toward a world in which consumers, not programmers, determine not only what they watch but when, where, and how. The dream of routing around cable companies just may be in sight.

You'll never hear Hastings point that out, however. Unlike many in the tech world, he's a quiet disrupter, sabotaging business models silently and irretrievably. His first hit was to the DVD business. Netflix, which lets subscribers hold on to movies for as long as they like, was cheaper, easier, and more convenient for consumers than building film libraries; DVD sales have plummeted as Netflix has grown. And while his streaming service would seem to present a similar threat to cable companies, Hastings argues that their real challenge comes from the Internet in general, not just Netflix. "I mean, will people disconnect their cable over time?" He shrugs. "Potentially." Hastings may undersell the impact of his service, but some of his partners don't share his gift for diplomacy. "Our goal is to have everyone cancel their cable subscription," Roku's Wood says.

Whether Hastings cops to it or not, that day could be coming soon. That's why, for Hastings to fully accomplish his vision, he'll have to go up against some of the most powerful incumbents in media: the cable companies and content providers that have successfully stymied or co-opted all previous entrepreneurial efforts. So far, Hastings has avoided the wrath of the giants by building his Netflix service surreptitiously, slowly amassing his library of streaming content and giving viewers new ways to access it. And now, even if the cable and content companies do take him on, it may be too late. Hastings' Trojan horse—Netflix's software, embedded on myriad consumer devices—is already in place.

It is odd, in an era when the Internet seems able to worm its way into every part of life, that nearly all of us still watch television the old-fashioned way, piped over cable or beamed in by satellite and available only in bloated packages of channels programmed by network executives. Breaking out of this system requires more patience, money, and technical expertise than the average couch potato is willing or able to expend: Plunk an expensive streaming device or PC tower in the living room, wire up a connection to the TV, and install the Boxee app or program a BitTorrent RSS feed to get the content. Watching live shows in real time requires an even more elaborate work-around. Cable companies have made some feints toward giving subscribers more control over what they watch, but most of their efforts have been lackluster. Verizon's FiOS TV offers access to a few user-generated Web sites; Comcast and Time Warner Cable are rolling out services that let subscribers stream cable channels to their PCs.

The set-top box has proven to be a closed and well-guarded fortress against a world of clouds and openness. The cable and satellite industries, and their partners in Hollywood, work strenuously to keep it that way. It's easy to see why: Those little boxes bankroll their business. While the cable companies offer telephone and broadband, TV subscriptions still account for about 60 percent of their revenue. About a third of those fees get funneled to cable networks like Disney and Discovery, where they account for at least half of their revenue. Another chunk of subscription revenue goes to movie studios, which make more than $1 billion a year charging premium channels like HBO for the right to air their films. Even broadcast networks like ABC and NBC, which don't make any money from cable bills, would still prefer that the content they make available online not be viewed on a TV set, because they can't sell as many ads for their Web versions. Fox crams 18 commercials into every Sunday night airing of The Simpsons, earning 54 cents per viewer. But, according to research firm Sanford C. Bernstein, Fox airs just three commercials for the same show on Hulu—a site it co-owns with NBC Universal and Disney—earning a measly 18 cents per viewer.

Netflix CEO Reed Hastings.

Photo: Robert Maxwell

The man who would overturn this decades-old system is an unlikely revolutionary. Hastings carries himself with a laconic modesty that contradicts an ambitious and restless mind. He has the deep tan of a dedicated snowboarder and a salt-and-pepper goatee that gives him a casual, approachable air. A quiet, hands-off leader, he sets the tone and objectives and lets his employees figure out how to execute them. His main directive is that everyone act like an adult: Netflix has no vacation policy (take as much as you need, when you need it), pay is flexible (stock or cash, your choice), and though firings are unusually common, severance checks are unusually generous. Hastings is comfortable creating his own rules for how to run a business; you don't see any management tomes in his office. In fact, he doesn't even have an office. The CEO prefers to stroll around, a ThinkPad in hand, pitching camp in an empty conference room or huddling in an engineer's cubicle to whiteboard some formula.

One recent morning, Hastings gathered a group of seven newly hired Netflixers in a sunny conference room on the roof of the company's headquarters. He does this once a month and, as always, kicks off the discussion by asking everyone to talk about the best movie they've seen in the past few weeks. He picks Jimmy Carter Man From Plains: "Five minutes in, I was hooked. The filmmaker did a good job making him not boring." The talk flows easily, but the goal is bigger than making everyone comfortable; he's reinforcing the idea that Netflix culture revolves around serving up content.

Since starting the company in 1997, Hastings' goal has always been the same: to deliver the right content in the fastest and most economical way. Obsessed with designing the perfect algorithm for helping viewers discover new movies, he has packed the place with mathematicians and engineers. They test everything, from the recommendations engine to the Web site's design. But if Hastings uses geeky number-crunching to help customers find their movies, his process of delivering them has been decidedly low tech: sending DVDs in red envelopes via the US Postal Service, which costs him roughly a quarter of his $1.4 billion in annual revenue.

Hastings has wanted to move beyond the silver discs for years, but his early attempts to deliver movies over the Net were slow and kludgy. In 2000, his engineers came up with a service that took 16 hours to download a two-hour movie. Hastings killed the project and disbanded the team. In 2003, a new group of engineers built a small, TV-connected Linux PC that could pull in movies. It cost $300 and took two hours to download a film. Again he wielded his ax. Hastings' decisions may have seemed coldhearted, but ultimately they were proven correct. Other competitors like Akimbo brought similar boxes to market—and failed.

It wasn't until 2006 that he tried again. By this time, the long-download problem had been solved by widespread adoption of broadband among consumers. Meanwhile, the spread of YouTube had gotten users used to the idea of streaming content rather than downloading and saving it. So Hastings put together another team of engineers, who developed a way to navigate unreliable home networks, allowing bitrates to shift midstream to maintain the best picture quality with the least amount of buffering.

But the technology was the easy part. Once Hastings decided not to release his own player, he encountered a different challenge: finding devices beyond Roku that would agree to host Netflix's streaming service. One of the first companies he turned to was Microsoft. Practically since releasing its Xbox in 2001, the company had dreamed of making the console into more than just a gaming machine for teenage boys. It offered more than 17,000 movies and TV shows over Xbox Live, but consumers mostly ignored them; apparently they still saw the console as a Halo delivery device. Providing unlimited access to Netflix's streaming library could change that. Microsoft executives were won over, but even they were surprised at the service's success: Within three months of the late 2008 launch, more than 1 million people had signed on, a huge percentage of whom had never touched an Xbox before. "There's a whole demographic—women—that we now pick up," says Robbie Bach, president of Microsoft's entertainment and devices division. "They always thought of Xbox as a hardcore gaming machine. It belonged in the kid's bedroom or the den or some place where 'my husband cocooned when he wanted to play games.' Now its front and center in the house because everyone wants to stream a movie."

Since then, a full Netflix pandemic has broken out. Microsoft incorporated the service into its Windows Media Center software, meaning anyone with Vista can stream Netflix to their TV. Hastings inked deals with Sony and Samsung to put the service into Bravia TVs and Blu-ray players, respectively. The service started showing up in TVs made by Vizio, the largest seller of LCD televisions in the country. And Broadcom began baking the software into some of its flatscreen chips, making it easy for any TV maker to offer sets pre-loaded with Netflix. (As an extra incentive, Netflix pays manufacturers a bounty for any new subscribers that sign up via their products.) Investment bank Piper Jaffray estimates that 25 percent of Netflix's 2.4 million new subscribers this year will come through one of the streaming devices.

With the device makers on board, Hastings had an even tougher task. He needed more and better content. The interface could be the slickest around, but nobody would tune to Netflix's service if it only had back-catalog flicks and old TV shows. In other words, Netflix needed Hollywood.

Despite having run a movie-distribution company, Hastings was far from a Hollywood insider. Netflix simply bought DVDs like any other customer (albeit one with a major movie jones), occasionally striking special revenue-sharing deals for certain titles. The studios couldn't do much: A section of the US copyright law known as the First Sale Doctrine states that, as long as you own it, you can basically do whatever you want with a physical disc. As one studio exec says, "We don't have a choice. We were backed into the business model."

But with online streaming, Netflix has no such advantage. The First Sale Doctrine gives Netflix the right to do what it wants with the disc, not the movie. Netflix suddenly needed to craft more-complicated licensing deals. Push too hard or offer the wrong incentives and the studios could block Netflix from getting good content; acquiesce too easily and Hollywood would happily impose intolerable rules regulating when a movie could be shown, on what platform, and for what price. Part of Netflix's promise is that it offers, like cable and broadcast TV, all-you-can-eat content. If the company bargained away that feature, its service would become just another pay-per-view platform.

To woo Hollywood, Hastings turned to Ted Sarandos, who oversees a staff of 75 at Netflix's Beverly Hills beachhead. Sarandos, a former executive at a video distribution company, serves as translator between the geeks and the studio executives. "There's a lot about the entertainment industry that drives Silicon Valley insane," Sarandos says. "Just the way things work, the politics of it, the pace of it."

Sarandos asked his team to use their data-mining skills to help him find deals. While other video providers might ask studios for a sack full of sure things—new releases by big-name stars—Netflix's engineers could dig through their queue and review databases to find sleeper hits that its users actually wanted to watch but that studios might be willing to license for a pittance. Earlier this year, for instance, Netflix jumped at the chance to stream a French film called Tell No One. The movie pulled in just $6 million at the US box office, but enough subscribers added it to their rental queues that Netflix was able to calculate an estimate of how popular the film would be. Almost immediately after Netflix started streaming it, Tell No One became the fourth-most-watched piece of content. "We have the rental history and the queue insight that enables us to go after things that other people may not be really even hunting," Sarandos says.

Unearthing overlooked gems is great, but Netflix's service will never take off until it can offer up its share of blockbusters. To get those titles, the company needed some way to hack the so-called windowing system, the complicated schedule that governs which distributors can show what films and in what format. First, national and international theatrical distributors pay to show a film in their theaters. Next, there's the DVD and pay-per-view windows. Then there's the combined $1.7 billion a year that channels like HBO, Starz, and Showtime spend to secure the exclusive rights to show movies to subscribers. (Each studio usually signs with just one pay channel; all Warner Bros. movies appear only on HBO, while Sony's go to Starz.) After a few months, the pay-TV networks hand off their rights to broadcasters and ad-supported cable stations. A few years later, the premium channels get the films back, giving them exclusive rights to air them. The windowing system can keep films locked up for years; Disney's National Treasure: Book of Secrets came out in 2007 and is spoken for until 2016. Unless Hastings and Sarandos could find a way around the windowing system, it would be a challenge to show any major movies that had been released in the recent past.

Then they discovered a loophole: Why couldn't Starz sell Netflix the right to air its movies, just as it did with Comcast? Starz had the pay-TV rights to newer titles, exactly what Netflix lacked. Netflix had nearly 9 million (now almost 11 million) subscribers; if it were a cable company, it would be number three, bigger than Cablevision and Charter combined. "We looked at our contract rights and saw that they were an aggregator of content just like the other distributors," says Starz CEO Robert Clasen.

Anthony Wood created the Roku media streamer while working at Netflix.

Photo: Robert Maxwell

In October 2008, the two companies announced a deal that would add 2,500 fresh titles to Netflix's service. The studios were stunned. "This is the last thing you want," moaned one studio executive. "More eyeballs with no incremental revenue."

Hastings' window probably won't stay open forever. Unhappy studios or cable companies could easily renegotiate their contract with Starz to discourage it from working with Netflix. Still, the deal kicked off what Hastings hopes will be an unstoppable virtuous cycle. If Netflix can use the Starz offerings to sign up more subscribers, those subscription fees will generate more revenue. And with more revenue, Netflix can afford to pay more studios for rights to more films—which will draw in still more subscribers. And so on. Ultimately, if Netflix can grow and maintain a big enough library by working directly with the studios, it won't need the likes of Starz. Sure, it could potentially overturn the way Hollywood has done business, but as long as the studios are getting paid, why should they mind? "Think of all things in Hollywood as 'money talks,'" Hastings says. "If we can generate enough money for studios, we can get any content we want."

As Hastings chips away at Hollywood, he's also moving as fast as possible to cement Netflix's presence in the next generation of home entertainment devices. He knows he has limited time before the rest of the movie-distribution industry realizes what has hit it. "We had DVD by mail mostly to ourselves for five years before Blockbuster attacked," he says. "And then they gave us hell for five years. So, as great as things are going now, I'm like, remember, hell will return."

It could come from anywhere. Maybe one day the studios decide they don't need Netflix and start dealing directly with device manufacturers. Or they could just jack up the fees they charge Netflix. Amazon or Apple could emerge as a tough competitor. Cable behemoths could use their power to block Netflix's access to content, or they could try to put together their own Netflix-like services. ("There is no reason why this isn't something we can compete with," says Peter Stern, chief strategy officer of Time Warner Cable.)

There are a million different ways for Netflix to fail. But that has always been the case. Netflix should have failed already, taken down by Blockbuster or Wal-Mart, kneecapped by Hollywood, made irrelevant by BitTorrent or iTunes. Yet time and again, the company has not only survived but quietly thrived—on the strength of its unique algorithms and its relentless focus on getting customers content they didn't even know they wanted.

Speaking to his new hires, Hastings lets slip a rare glimpse of immodesty. "When people connect with a movie, it really makes them happy, and that's fundamentally what we're trying to do," he says. "Today you love one out of three movies that you watch. If we can raise that to two out of three, we can completely transform the market and increase human happiness." He makes it all sound so easy—never mind the powerful competitors. Ultimately, the key to film nirvana, whether delivered by DVD or streamed over the Internet, can be as simple as cracking an equation.

The chairman of the Federal Communications Commission today called for more aggressive action to keep online traffic moving freely, proposing two new government policies to prevent telecommunications companies from restricting websites and other services on the Internet.

The chairman of the Federal Communications Commission today called for more aggressive action to keep online traffic moving freely, proposing two new government policies to prevent telecommunications companies from restricting websites and other services on the Internet.

It had taken the better part of a decade, but Reed Hastings was finally ready to unveil the device he thought would upend the entertainment industry. The gadget looked as unassuming as the original iPod—a sleek black box, about the size of a paperback novel, with a few jacks in back—and Hastings, CEO of Netflix, believed its impact would be just as massive. Called the Netflix Player, it would allow most of his company's regular DVD-by-mail subscribers to stream unlimited movies and TV shows from Netflix's library directly to their television—at no extra charge.

It had taken the better part of a decade, but Reed Hastings was finally ready to unveil the device he thought would upend the entertainment industry. The gadget looked as unassuming as the original iPod—a sleek black box, about the size of a paperback novel, with a few jacks in back—and Hastings, CEO of Netflix, believed its impact would be just as massive. Called the Netflix Player, it would allow most of his company's regular DVD-by-mail subscribers to stream unlimited movies and TV shows from Netflix's library directly to their television—at no extra charge.

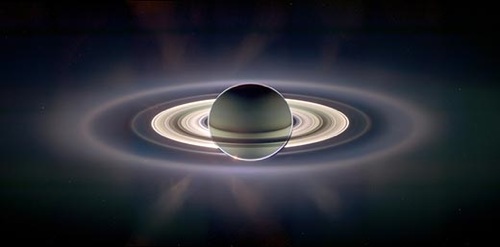

Smithsonian posted an absolutely breathtaking gallery of images taken by space probes over the last decade.

Smithsonian posted an absolutely breathtaking gallery of images taken by space probes over the last decade. An awful lot of energy could be saved if only people shared things more – especially their homes.

An awful lot of energy could be saved if only people shared things more – especially their homes. To many, going green means moving to the countryside. To reduce your carbon footprint, though, you'd be better off cultivating an urban idyll.

To many, going green means moving to the countryside. To reduce your carbon footprint, though, you'd be better off cultivating an urban idyll. Fewer than 1 in 150 children die before age 5 in developed countries, and a lot of the credit must go to vaccines.

Fewer than 1 in 150 children die before age 5 in developed countries, and a lot of the credit must go to vaccines.