The Daily Drift

Yeah, it's like that ...

Carolina Naturally is read in 192 countries around the world daily.

Hot enough for ya?! ...

Today is Hot Enough For Ya Day

Don't forget to visit our sister blog: It Is What It Is

| 1540 | Thomas Cromwell is beheaded on Tower Hill in England. | |

| 1627 | Sir George Calvert arrives in Newfoundland to develop his land grant. | |

| 1637 | King Charles of England hands over the American colony of Massachusetts to Sir Fernando Gorges, one of the founders of the Council of New England. | |

| 1664 | Wealthy, non-church members in Massachusetts are given the right to vote. | |

| 1793 | The French garrison at Mainz, Germany, falls to the Prussians. | |

| 1803 | Irish patriots throughout the country rebel against Union with Great Britain. | |

| 1829 | William A. Burt patents his "typographer," an early typewriter. | |

| 1849 | German rebels in Baden capitulate to the Prussians. | |

| 1863 | Bill Andeson and his Confederate Bushwackers gut the railway station at Renick, Missouri. | |

| 1865 | William Booth founds the Salvation Army. | |

| 1868 | The 14th Amendment is ratified, granting citizenship to African Americans. | |

| 1885 | Ulysses S. Grant dies of throat cancer at the age of 63. | |

| 1894 | Japanese troops take over the Korean imperial palace. | |

| 1903 | The Ford Motor Company sells its first automobile, the Model A. | |

| 1944 | Soviet troops take Lublin, Poland as the German army retreats. | |

| 1962 | The Geneva Conference on Laos forbids the United States to invade eastern Laos. | |

| 1995 | Two astronomers, Alan Hale in New Mexico and Thomas Bopp in Arizona, almost simultaneouly discover a comet. |

The

particularly American form of cooking we call the barbecue has a long

history -in fact, it was well established long before Europeans arrived.

Since the early explorers passed the technique around to colonists,

different styles sprang up, now loosely categorized as Carolina, Texas,

Memphis, and Kansas City. The differences can be traced to what was

available and what flavors one's ancestors liked. For example,

Southerners often insist that real barbecue is made of pork. It's

tradition.

The

particularly American form of cooking we call the barbecue has a long

history -in fact, it was well established long before Europeans arrived.

Since the early explorers passed the technique around to colonists,

different styles sprang up, now loosely categorized as Carolina, Texas,

Memphis, and Kansas City. The differences can be traced to what was

available and what flavors one's ancestors liked. For example,

Southerners often insist that real barbecue is made of pork. It's

tradition.Unlike cows, which required large amounts of feed and enclosed spaces, pigs could be set loose in forests to eat when food supplies were running low. The pigs, left to fend for themselves in the wild, were much leaner upon slaughter, leading Southerns to use the slow-and-low nature of barbecue to tenderize the meat. And use it they did. During the pre-Civil War years, Southerners ate an average of five pounds of pork for every one pound of cattle. Their dependence on this cheap food supply eventually became a point of patriotism, and Southerners took greater care raising their pigs, refusing to export their meat to the northern states. By this time, however, the relationship between the barbecue and pork had been deeply forged.But Texas is a different story. And barbecue sauce reflects the traditions that immigrants brought from the Old World. Read how these factors came together at Smithsonian's Food and Think blog.

In

this December 2012 photo provided by the U.S. Department of Energy,

Ames Laboratory, materials scientist Ryan Ott, left, and research

technician Ross Anderson examine an ingot of magnesium and rare-earth

metals as part of a project to optimize the process to reclaim rare

earths from scraps of rare-earth-containing magnets in Ames, Iowa.

Across the West, early miners digging for gold, silver and copper had no

idea that one day something even more valuable would be hidden in the

piles of dirt and rocks they tossed aside. Now there ís a rush in the

U.S. to find key components of cellphones, televisions, weapons systems,

wind turbines, MRI machines and the regenerative brakes in hybrid cars,

a group of versatile minerals on the periodic table called rare earth

elements and old mining tailings piles just might be the answer.

In

this December 2012 photo provided by the U.S. Department of Energy,

Ames Laboratory, materials scientist Ryan Ott, left, and research

technician Ross Anderson examine an ingot of magnesium and rare-earth

metals as part of a project to optimize the process to reclaim rare

earths from scraps of rare-earth-containing magnets in Ames, Iowa.

Across the West, early miners digging for gold, silver and copper had no

idea that one day something even more valuable would be hidden in the

piles of dirt and rocks they tossed aside. Now there ís a rush in the

U.S. to find key components of cellphones, televisions, weapons systems,

wind turbines, MRI machines and the regenerative brakes in hybrid cars,

a group of versatile minerals on the periodic table called rare earth

elements and old mining tailings piles just might be the answer. In

this 1905 photo provided by the U.S. Geological Survey is a channel in

bedrock worn by tailings of the Cherokee hydraulic mine in Butte County,

Calif. Across the West, early miners digging for gold, silver and

copper had no idea that one day something even more valuable would be

hidden in the piles of dirt and rocks they tossed aside. Now there’s a

rush in the U.S. to find key components of cellphones, televisions,

weapons systems, wind turbines, MRI machines and the regenerative brakes

in hybrid cars, a group of versatile minerals on the periodic table

called rare earth elements and old mining tailings piles just might be

the answer.

In

this 1905 photo provided by the U.S. Geological Survey is a channel in

bedrock worn by tailings of the Cherokee hydraulic mine in Butte County,

Calif. Across the West, early miners digging for gold, silver and

copper had no idea that one day something even more valuable would be

hidden in the piles of dirt and rocks they tossed aside. Now there’s a

rush in the U.S. to find key components of cellphones, televisions,

weapons systems, wind turbines, MRI machines and the regenerative brakes

in hybrid cars, a group of versatile minerals on the periodic table

called rare earth elements and old mining tailings piles just might be

the answer.  In

this undated photo provided by the U.S. Geological Survey is a rock

sample being analyzed in a Denver laboratory consisting of quartz, fine

grain (microscopic) pyrite, galena and sphalerite. The USGS Mineral

Resources program is looking at samples from previously mined ore that

may contain critical minerals including rare earth elements. Across the

West, early miners digging for gold, silver and copper had no idea that

one day something even more valuable would be hidden in the piles of

dirt and rocks they tossed aside. Now there's a rush in the U.S. to find

key components of cellphones, televisions, weapons systems, wind

turbines, MRI machines and the regenerative brakes in hybrid cars, a

group of versatile minerals on the periodic table called rare earth

elements and old mining tailings piles just might be the answer.

In

this undated photo provided by the U.S. Geological Survey is a rock

sample being analyzed in a Denver laboratory consisting of quartz, fine

grain (microscopic) pyrite, galena and sphalerite. The USGS Mineral

Resources program is looking at samples from previously mined ore that

may contain critical minerals including rare earth elements. Across the

West, early miners digging for gold, silver and copper had no idea that

one day something even more valuable would be hidden in the piles of

dirt and rocks they tossed aside. Now there's a rush in the U.S. to find

key components of cellphones, televisions, weapons systems, wind

turbines, MRI machines and the regenerative brakes in hybrid cars, a

group of versatile minerals on the periodic table called rare earth

elements and old mining tailings piles just might be the answer. In

this 1905 photo provided by the U.S. Geological Survey are tailings

from hydraulic mines on Spring Creek in Nevada County, Calif. Across the

West, early miners digging for gold, silver and copper had no idea that

one day something even more valuable would be hidden in the piles of

dirt and rocks they tossed aside. Now there’s a rush in the U.S. to find

key components of cellphones, televisions, weapons systems, wind

turbines, MRI machines and the regenerative brakes in hybrid cars, a

group of versatile minerals on the periodic table called rare earth

elements and old mining tailings piles just might be the answer.

In

this 1905 photo provided by the U.S. Geological Survey are tailings

from hydraulic mines on Spring Creek in Nevada County, Calif. Across the

West, early miners digging for gold, silver and copper had no idea that

one day something even more valuable would be hidden in the piles of

dirt and rocks they tossed aside. Now there’s a rush in the U.S. to find

key components of cellphones, televisions, weapons systems, wind

turbines, MRI machines and the regenerative brakes in hybrid cars, a

group of versatile minerals on the periodic table called rare earth

elements and old mining tailings piles just might be the answer.  In

this undated photo released by the U.S. Department of Agriculture are

rare-earth oxides, clockwise from top center: praseodymium, cerium,

lanthanum, neodymium, samarium, and gadolinium. Across the West, early

miners digging for gold, silver and copper had no idea that one day

something even more valuable would be hidden in the piles of dirt and

rocks they tossed aside. Now there’s a rush in the U.S. to find key

components of cellphones, televisions, weapons systems, wind turbines,

MRI machines and the regenerative brakes in hybrid cars, a group of

versatile minerals on the periodic table called rare earth elements and

old mining tailings piles just might be the answer.

In

this undated photo released by the U.S. Department of Agriculture are

rare-earth oxides, clockwise from top center: praseodymium, cerium,

lanthanum, neodymium, samarium, and gadolinium. Across the West, early

miners digging for gold, silver and copper had no idea that one day

something even more valuable would be hidden in the piles of dirt and

rocks they tossed aside. Now there’s a rush in the U.S. to find key

components of cellphones, televisions, weapons systems, wind turbines,

MRI machines and the regenerative brakes in hybrid cars, a group of

versatile minerals on the periodic table called rare earth elements and

old mining tailings piles just might be the answer.

|

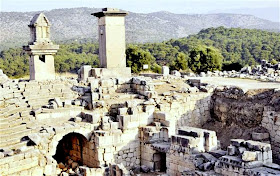

| Archaelogists are hoping to find new artifacts in Xanthos this season [Credit: DHA] |

|

| The southeast tower of the citadel from the NW [Credit: WikiCommons] |

|

| Fallen blocks of the southeast tower being lifted to their original positions [Credit: To Vima] |