Without ever setting

sail, Marie Tharp mapped the ocean floor and made a discovery that shook

the foundations of geology. So why did the giants of her field dismiss

her findings as "girl talk"?

Marie Tharp spent the fall of 1952

hunched over a drafting table, surrounded by charts, graphs, and jars

of India ink. Nearby, spread across several additional tables, lay her

project—the largest and most detailed map ever produced of a part of

the world no one had ever seen.

For centuries, scientists had

believed that the ocean floor was basically flat and featureless—it was

too far beyond reach to know otherwise. But the advent of sonar had

changed everything. For the first time, ships could “sound out” the

precise depths of the ocean below them. For five years, Tharp’s

colleagues at Columbia University had been crisscrossing the Atlantic,

recording its depths. Women weren’t allowed on these research trips—the

lab director considered them bad luck at sea—so Tharp wasn’t on board.

Instead, she stayed in the lab, meticulously checking and plotting the

ships’ raw findings, a mass of data so large it was printed on a

5,000-foot scroll. As she charted the measurements by hand on sheets of

white linen, the floor of the ocean slowly took shape before her.

Tharp

spent weeks creating a series of six parallel profiles of the Atlantic

floor stretching from east to west. Her drawings showed—for the first

time—exactly where the continental shelf began to rise out of the

abyssal plain and where a large mountain range jutted from the ocean

floor. That range had been a shock when it was discovered in the 1870s

by an expedition testing routes for transatlantic telegraph cables, and

it had remained the subject of speculation since; Tharp’s charting

revealed its length and detail.

Her maps also showed something

else—something no one expected. Repeating in each was “a deep notch

near the crest of the ridge,” a V-shaped gap that seemed to run the

entire length of the mountain range. Tharp stared at it. It had to be a

mistake.

She crunched and re-crunched the numbers for weeks on

end, double- and triple-checking her data. As she did, she became more

convinced that the impossible was true: She was looking at evidence of a

rift valley, a place where magma emerged from inside the earth,

forming new crust and thrusting the land apart. If her calculations

were right, the geosciences would never be the same.

A few decades before, a German geologist named

Alfred Wegener had put forward the radical theory that the continents of

the earth had once been connected and had drifted apart. In 1926, at a

gathering of the American Association of Petroleum Geologists, the

scientists in attendance rejected Wegener’s theory and mocked its maker.

No force on Earth was thought powerful enough to move continents. “The

dream of a great poet,” opined the director of the Geological Survey

of France: “One tries to embrace it, and finds that he has in his arms a

little vapor or smoke.” Later, the president of the American

Philosophical Society deemed it “utter, damned rot!”

In

the 1950s, as Tharp looked down at that tell-tale valley, Wegener’s

theory was still considered verboten in the scientific community—even

discussing it was tantamount to heresy. Almost all of Tharp’s

colleagues, and practically every other scientist in the country,

dismissed it; you could get fired for believing in it, she later

recalled. But Tharp trusted what she’d seen. Though her job at Columbia

was simply to plot and chart measurements, she had more training in

geology than most plotters—more, in fact, than some of the men she

reported to. Tharp had grown up among rocks. Her father worked for the

Bureau of Chemistry and Soils, and as a child, she would accompany him

as he collected samples. But she never expected to be a mapmaker or

even a scientist. At the time, the fields didn’t welcome women, so her

first majors were music and English. After Pearl Harbor, however,

universities opened up their departments. At the University of Ohio,

she discovered geology and found a mentor who encouraged her to take

drafting. Because Tharp was a woman, he told her, fieldwork was out of

the question, but drafting experience could help her get a job in an

office like the one at Columbia. After graduating from Ohio, she

enrolled in a program at the University of Michigan, where, with men off

fighting in the war, accelerated geology degrees were offered to

women. There, Tharp became particularly fascinated with geomorphology,

devouring textbooks on how landscapes form. A rock formation’s

structure, composition, and location could tell you all sorts of things

if you knew how to look at it.

Studying the crack in the ocean

floor, Tharp could see it was too large, too contiguous, to be anything

but a rift valley, a place where two masses of land had separated.

When she compared it to a rift valley in Africa, she grew more certain.

But when she showed Bruce Heezen, her research supervisor (four years

her junior), “he groaned and said, ‘It cannot be. It looks too much

like continental drift,’” Tharp wrote later. “Bruce initially dismissed

my interpretation of the profiles as ‘girl talk.’” With the lab’s

reputation on the line, Heezen ordered her to redo the map. Tharp went

back to the data and started plotting again from scratch.

Heezen

and Tharp were often at odds and prone to heated arguments, but they

worked well together nonetheless. He was the avid collector of

information; she was the processor comfortable with exploring deep

unknowns. As the years went by, they spent more and more time together

both in and out of the office. Though their platonic-or-not relationship

confused everyone around them, it seemed to work.

In late 1952,

as Tharp was replotting the ocean floor, Heezen took on another

deep-sea project searching for safe places to plant transatlantic

cables. He was creating his own map, which plotted earthquake

epicenters in the ocean floor. As his calculations accumulated, he

noticed something strange: Most quakes occurred in a nearly continuous

line that sliced down the center of the Atlantic. Meanwhile, Tharp had

finished her second map—a physiographic diagram giving the ocean floor a

3-D appearance—and sure enough, it showed the rift again. When Heezen

and Tharp laid their two maps on top of each other on a light table,

both were stunned by how neatly the maps fit. The earthquake line

threaded right through Tharp’s valley.

They

moved on from the Atlantic and began analyzing data from other oceans

and other expeditions, but the pattern kept repeating. They found

additional mountain ranges, all seemingly connected and all split by

rift valleys; within all of them, they found patterns of earthquakes.

“There was but one conclusion,” Tharp wrote. “The mountain range with

its central valley was more or less a continuous feature across the face

of the earth.” The matter of whether their findings offered evidence

of continental drift kept the pair sparring, but there was no denying

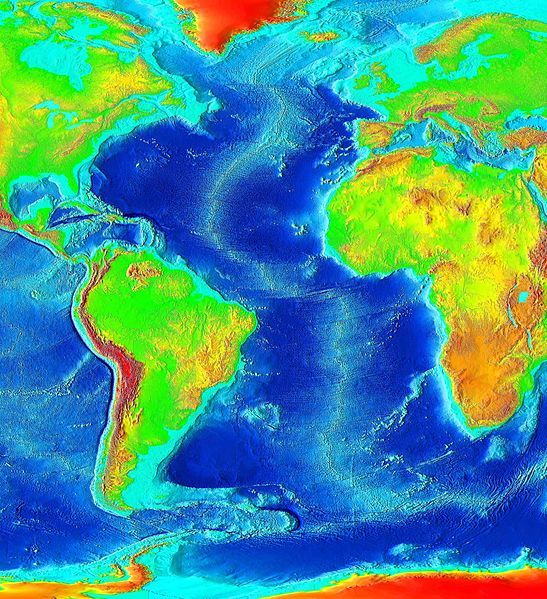

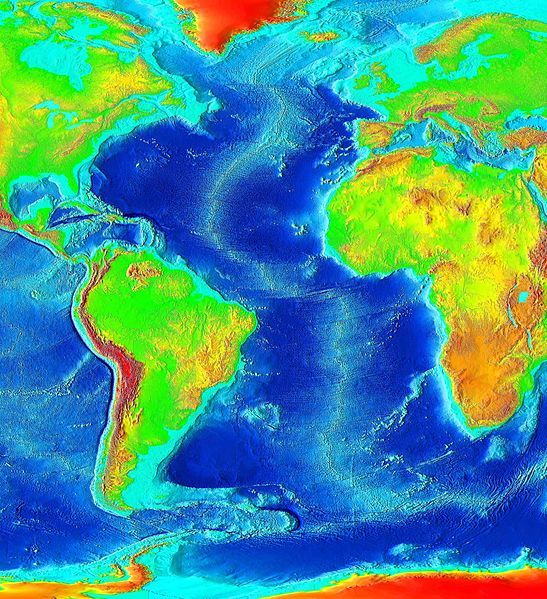

they had made a monumental discovery: the mid-ocean ridge, a

40,000-mile underwater mountain range that wraps around the globe like

the seams on a baseball. It’s the largest single geographical feature

on the planet.

In 1957, Heezen took some of the

findings public. After he presented on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge at

Princeton, one eminent geologist responded, "Young man, you have shaken

the foundations of geology!” He meant it as a compliment, but not

everyone was so impressed. Tharp later remembered that the reaction

“ranged from amazement to skepticism to scorn.” Ocean explorer Jacques

Cousteau was one of the doubters. He’d tacked Tharp’s map to a wall in

his ship’s mess hall. When he began filming the Atlantic Ocean’s floor

for the first time, he was determined to prove Tharp’s theory wrong.

But what he ultimately saw in the footage shocked him. As his ship

approached the crest of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, he came upon a deep

valley splitting it in half, right where Tharp’s map said it would be.

Cousteau and his crew were so astonished that they turned around, went

back, and filmed again. When Cousteau screened the video at the

International Oceanographic Congress in 1959, the audience gasped and

shouted for an encore. The terrain Tharp had mapped was undeniably

real.

1959 was the same year that Heezen, still skeptical,

presented a paper hoping to explain the rift. The Expanding Earth

theory he’d signed on to posited that continents were moving as the

planet that contained them grew. (He was wrong.) Other hypotheses soon

joined the chorus of explanations about how the rift had occurred. It

was the start of an upheaval in the geologic sciences. Soon “it became

clear that existing explanations for the formation of the earth’s

surface no longer held,” writes Hali Felt in

Soundings: The Story of the Remarkable Woman Who Mapped the Ocean Floor.

Tharp

stayed out of these debates and simply kept working. She disliked the

spotlight and consented to present a paper only once, on the condition

that a male colleague do all the talking. “There’s truth to the old

cliché that a picture is worth a thousand words and that seeing is

believing,” she wrote. “I was so busy making maps I let them argue. I

figured I’d show them a picture of where the rift valley was and where

it pulled apart.”

By 1961, the idea that she’d put forward nearly a

decade before—that the rift in the Mid-Atlantic Ridge had been caused

by land masses pulling apart—had finally reached widespread acceptance.

The National Geographic Society commissioned Tharp and Heezen to make

maps of the ocean floor and its features, helping laypeople visualize

the vast plates that allowed the earth’s crust to move. Throughout the

1960s, a slew of discoveries helped ideas such as seafloor spreading

and plate tectonics gain acceptance, bringing with them a cascade of

new theories about the way the planet and life on it had evolved. Tharp

compared the collective eye-opening to the Copernican revolution.

“Scientists and the general public,” she wrote, “got their first

relatively realistic image of a vast part of the planet that they could

never see.”

Tharp herself had never seen it either. Some 15 years

after she started mapping the seafloor, Tharp finally joined a

research cruise, sailing over the features she’d helped discover. Women

were generally still not welcome, so Heezen helped arrange her spot.

The two kept working closely together, sometimes fighting fiercely,

until his death in 1977. Outside the lab, they maintained separate

houses but dined and drank like a married couple. Their work had linked

them for life.

In

1997, Tharp, who had long worked patiently in Heezen’s shadow,

received double honors from the Library of Congress, which named her one

of the four greatest cartographers of the 20th century and included

her work in an exhibit in the 100th-anniversary celebration of its

Geography and Map Division. There, one of her maps of the ocean floor

hung in the company of the original rough draft of the Declaration of

Independence and pages from Lewis and Clark’s journals. When she saw it,

she started to cry. But Tharp had known all along that the map she

created was remarkable, even when she was the only one who believed.

“Establishing the rift valley and the mid-ocean ridge that went all the

way around the world for 40,000 miles—that was something important,”

she wrote. “You could only do that once. You can’t find anything bigger

than that, at least on this planet.”