Not to mention downright stupid

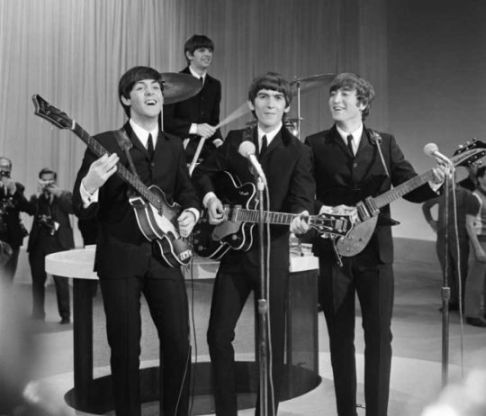

We’ve all made mistakes … but probably not big mistakes like making snot beer, saying no to The Beatles, or turning down the patent for the telephone. In fact, here are some of the biggest business blunders in history:Turning Down The Beatles

SHOULD WE SIGN THEM UP?

Executives: Mike Smith and Dick Rowe, executives in charge of evaluating new talent for the London office of Decca Records.Background: On December 13, 1961, Mike Smith traveled to Liverpool to watch a local rock ‘n’ roll band perform. He decided they had talent, and invited them to audition on New Year’s Day 1962. The group made the trip to London and spent two hours playing 15 different songs at the Decca studios. Then they went home and waited for an answer.

They waited for weeks.

Decision: Finally, Rowe told the band’s manager that the label wasn’t interested, because they sounded too much like a popular group called The Shadows. In one of the most famous of all rejection lines, he said: "Not to mince words, Mr. Epstein, but we don’t like your boys’ sound. Groups are out; four-piece groups with guitars particularly are finished."

Impact: The group was The Beatles, of course. They eventually signed with EMI Records, started a trend back to guitar bands, and ultimately became the most popular band of all time. Ironically, "within two years, EMI’s production facilities became so stretched that Decca helped them out in a reciprocal arrangement, to cope with the unprecedented demand for Beatles records."

Turning Down E.T.

SHOULD WE LET THAT DIRECTOR USE OUR CANDY IN HIS FILM?

Executives: John and Forrest Mars, the owners of Mars Inc., makers of M&M’s

Executives: John and Forrest Mars, the owners of Mars Inc., makers of M&M’sBackground: In 1981, Universal Studios called Mars and asked for permission to use M&M’s in a new film they were making. This was (and is) a fairly common practice. Product placement deals provide filmmakers with some extra cash or promotion opportunities. In this case, the director was looking for a cross-promotion. He’d use the M&M’s, and Mars could help promote the movie.

Decision: The Mars brothers said "No."

Impact: The film was E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial, directed by Stephen Spielberg. The M&M’s were needed for a crucial scene: Eliott, the little boy who befriended the alien, uses candies to lure E.T. into his house.

Instead, Universal Studios went to Hershey’s and cut a deal to use a new product called Reese’s Pieces. Initial sales of Reese’s Pieces had been light. But when E.T. became a top-grossing film – generating tremendous publicity for "E.T.’s favorite candy" – sales exploded. They tripled within two weeks and continued climbing for months afterward. "It was the biggest marketing coup in history," says Jack Dowd, the Hershey’s executive who approved the movie tie-in. "We got immediate recognition for our product. We would normally have to pay 15 or 20 million bucks for it."

Selling M*A*S*H For Peanuts

HOW DO WE COME UP WITH SOME QUICK CASH?

Executives: Executives of 20th Century Fox’s TV division (pre-Murdoch)

Executives: Executives of 20th Century Fox’s TV division (pre-Murdoch)Background: No one at Fox expected much from M*A*S*H when it debuted on TV in 1972. Execs simply wanted to make a cheap series by using the M*A*S*H movie set again – so it was a surprise when it became Fox’s only hit show. Three years later, the company was hard up for cash. When the M*A*S*H ratings started to slip after two of its stars left, Fox execs panicked.

Decision: They decided to raise cash by selling the syndication rights to the first seven seasons of M*A*S*H on a futures basis: local TV stations could pay in 1975 for shows they couldn’t broadcast until October 1979 – four years away. Fox made no guarantees that the should would still be popular; $13,000 per episodes was non-refundable. But enough local stations took the deal so that Fox made $25 million. They celebrated …

Impact: … but prematurely. When M*A*S*H finally aired in syndication in 1979, it was still popular (in fact, it ranked #3 that year). It became one of the most successful syndicated shows ever, second only to "I Love Lucy." Each of the original 168 episodes grossed over $1 million for local TV stations; Fox got nothing.

What Use is the Telephone, the Electrical Toy?

SHOULD WE BUY THIS INVENTION?

Executive: William Orton, president of the Western Union Telegraph Company in 1876.

Background: In 1876, Western Union had a monopoly on the telegraph, the world’s most advanced communications technology. This made it one of America’s richest and most powerful companies, "with $41 million in capital and the pocketbooks of the financial world behind it." So when Gardiner Greene Hubbard, a wealthy Bostonian, approached Orton with an offer to sell the patent for a new invention Hubbard had helped to fund, Orton treated it as a joke. Hubbard was asking for $100,000!

Decision: Orton bypassed Hubbard and drafted a response directly to the inventor. "Mr. Bell," he wrote, "after careful consideration of your invention, while it is a very interesting novelty, we have come to the conclusion that it has no commercial possibilities… What use could this company make of an electrical toy?"

Impact: The invention, the telephone, would have been perfect for Western Union. The company had a nationwide network of telegraph wires in place, and the inventor, 29-year-old Alexander Graham Bell, had shown that his telephone worked quite well on telegraph lines. All the company had to do was hook telephones up to its existing lines and it would have had the world’s first nationwide telephone network in a matter of months.

Instead, Bell kept the patent and in a few decades his telephone company, "renamed American Telephone and Telegraph (AT&T), had become the largest corporation in America … The Bell patent – offered to Orton for a measly $100,000 – became the single most valuable patent in history."

Ironically, less than two years of turning Bell down, Orton realized the magnitude of his mistake and spent millions of dollars challenging Bell’s patents while attempting to build his own telephone network (which he was ultimate forced to hand over to Bell.) Instead of going down in history as one of the architects of the telephone age, he is instead remember for having made one of the worst decisions in American business history.

Let’s Make Snot Beer!

HOW DO WE COMPETE WITH BUDWEISER?

Executive: Robert Uihlein, Jr., head of the Schlitz Brewing Company in Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

Executive: Robert Uihlein, Jr., head of the Schlitz Brewing Company in Milwaukee, Wisconsin.Background: in the 1970s, Schlitz was America’s #2 beer, behind Budweiser. It had been #1 until 1957 and has pursued Bud ever since. In the 1970s, Uihlein came up with a strategy to compete against Anheuser-Busch. He figured that if he could cut the cost of ingredients used in his beer and speed up the brewing process at the same time, he could brew more beer in the same amount of time for less money … and earn higher profits.

Decision: Uihlein cut the amount of time it took to brew Schlitz from 40 days to 15, and replaced much of the barley malt in the beer with corn syrup – which was cheaper. He also switched from one type of foam stabilizer to another to get around new labeling laws that would have required the original stabilizer to be disclosed on the label.

Impact: Uihlein got what he wanted: a cheaper, more profitable beer that made a lot of money … at first. But it tasted terrible, and tended to break down so quickly as the cheap ingredients bonded together and sank to the bottom of the can – forming a substance that "looked disconcertingly like mucus." Philip Van Munchings writes in Beer Blast:

Suddenly Schlitz found itself shipping out a great deal of apparently snot-ridden beer. The brewery knew about it pretty quickly and made a command decision – to do nothing … Uihlein declined a costly recall for months, wagering that not much of the beer would be subjected to the kinds of temperatures at which most haze forms. He lost the bet, sales plummeted … and Schlitz began a long steady slide from the top three.Schlitz finally caved in and recalled 10 million cans of the snot beer. But their reputation was ruined and sales never recovered. In 1981, they shut down their Milwaukee brewing plant; the following year the company was purchased by rival Stroh’s. One former mayor of Milwaukee compared the brewery’s fortunes to the sinking of the Titanic, asking "How could that big of a business go under so fast?"

Model T is Forever!

SHOULD WE INTRODUCE A NEW CAR?

Executive: Henry Ford, founder of the Ford Motor CompanyBackground: When Henry Ford first marketed the Model

T in 1908, it was a state-of-the-art automobile. "There were cheaper cars on the market," writes Robert Lacey in Ford: The Men and Their Machine, "but no one could offer the same combination of innovation and reliability." Over the years, the price went down dramatically … and as the first truly affordable quality automobile, the Model T revolutionized American culture.

Decision: The Model T was the only car that the Ford Motor Co. made. As the auto industry grew and competition got stiffer, everyone in the company – from Ford’s employees to his family – pushed him to update the design. Lacey writes:

The first serious suggestions that the Model T might benefit from some major updating had been made when the car was only four years old. In 1912 Henry Ford had taken [his family] on their first visit to Europe, and on his return he discovered that his [chief aides] had prepared a surprise for him. [They] had labored to produce a new, low-slung version of the Model T, and the prototype stood in the middle of the factory floor, its gleaming red lacquer-work polished to a high sheen.Ford proceeded to destroy the whole car with his bare hands. It was a message to everyone around him not to mess with his prize creation. Lacey concludes: "The Model T had been the making of Henry Ford, lifting him from being any other Detroit automobile maker to becoming car maker to the world. It had yielded him untold riches and power and pleasure, and it was scarcely surprising that he should feel attached to it. But as the years went by, it became clear that Henry Ford had developed a fixation with his masterpiece which was almost unhealthy."

"He had his hands in his pockets," remembered one eyewitness, "and he walked around the car three or four times, looking at it very closely … Finally, he got to the left-hand side of the car that was facing me, and he takes his hands out, gets hold of the door, and bang! He ripped the door right off! God! How the man done it, I don’t know!"

Ford had made his choice clear. In 1925, after more than 15 years on the market, the Model T was pretty much the same car it had been when it debuted. It still had the same noisy, underpowered four-cylinder engine, obsolete "planetary" transmission, and horse-buggy suspension that it had in the very beginning. Sure, Ford made a few concessions to the changing times, such as balloon tires, an electric starter, and a gas pedal on the floor. And by the early 1920s, the Model T was available in a variety of colors beyond Ford black. But the Model T was still … a Model T. "You can paint up a barn," one hurting New York Ford dealer complained, "but it will still be a barn and not a parlor."

Impact: While Ford rested on his laurels for a decade and a half, his competitors continued to innovate. Four-cylinder engines gave way to more powerful six-cylinder engines with manual clutch-and-gearshift transmissions. These new cars were powerful enough to travel at high speeds made possible by the country’s new paved highways. Ford’s "Tin Lizzie," designed in an era of dirt roads, was not.

Automobile buyers took notice and began trading up; Ford’s market share slid to 57% of U.S. automobile sales in 1923 down to 45% in 1925, and to 34% in 1926, as companies like Dodge and General Motors steadily gained ground. By the time Ford finally announced, that a replacement for the Model T was in the works in May 1927, the company had already lost the battle. That year, Chevrolet sold more cars than Ford for the first time. Ford regained first place in 1929 thanks to strong sales of its new Model A, but Chevrolet passed it again the following year and never looked back. "From 1930 onwards," Robert Lacey writes, "the once-proud Ford Motor Company had to be content with second place."

MORE BAD BUSINESS DECISIONS

ROSS PEROT

In 1979, Perot employed some of his well-known business acumen and foresaw that Bill Gates was on his way to building Microsoft into a great company. So he offered to buy him out. Gates says Perot offered between $6 million and $15 million; Perot says that Gates wanted $40 million to $60 million. Whatever the numbers were, the two couldn’t come to terms, and Perot walked away empty-handed. Today Microsoft is worth hundreds of billions of dollars.SAN FRANCISCO CHRONICLE

In 1979, the Washington Post offered the Chronicle the opportunity to syndicate a series of articles that two reporters named Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein were writing about a break-in at the Democratic headquarters at Washington, D.C.’s Watergate Hotel. Owner Charles Thieriot said no. "There will be no West Coast interest in the story," he explained. Thus, his rival, the San Francisco Examiner, was able to purchase the rights to the hottest news story of the decade for $500.W.T. GRANT CO.

In the mid-1970s, executives at the W.T. Grant variety store chain, one of the nation’s largest retailers, decided that the best way to increase sales was to increase the number of customers … by offering credit. It put tremendous "negative incentive" pressure on store managers to issue credit. Employees who didn’t meet their credit quotas risked complete humiliation. They had pies thrown in their faces, were forced to push peanuts across the floor with their noses, and were sent through hotel lobbies wearing only diapers. Eager to avoid such total embarrassment, store managers gave credit "to anyone who breathed," including untold thousands of customers who were bad risks. W.T. Grant racked up $800 million worth of bad debts before it finally collapsed in 1977.ABC-TV

In 1984, Bill Cosby gave ABC-TV first shot at buying a sitcom he’d created – and would star in – about an upscale black family. But ABC turned him down, apparently "believing the show lacked bite and that viewers wouldn’t watch an unrealistic portrayal of blacks as wealthy, well-educated professionals."So Cosby sold his show to NBC instead. What happened? Nothing much – The Cosby Show remained #1 show for four straight years, was a rating winner throughout its eight-year run, lifted NBC from its 10-year status as a last-place network to first place, resurrected TV comedy, and became the most profitable series ever broadcast.

DIGITAL RESEARCH

IBM once hired Microsoft founder Bill Gates to come up with the operating software for a new computer that IBM was rushing to market … and Gates turned to a company called Digital Research. He set up a meeting between owner Gary Kildall and IBM … but Kildall couldn’t make the meeting and sent his wife, Dorothy McEwen, instead. McEwen, who handled contract negotiations for Digital Research, felt that the contract IBM was offering would allow the company to incorporate features from Digital’s software into its own proprietary software – which would then compete against Digital. So she turned the contract down. Bill Gates went elsewhere, eventually coming up with a program called DOS, the software that put Microsoft on the map.

IBM once hired Microsoft founder Bill Gates to come up with the operating software for a new computer that IBM was rushing to market … and Gates turned to a company called Digital Research. He set up a meeting between owner Gary Kildall and IBM … but Kildall couldn’t make the meeting and sent his wife, Dorothy McEwen, instead. McEwen, who handled contract negotiations for Digital Research, felt that the contract IBM was offering would allow the company to incorporate features from Digital’s software into its own proprietary software – which would then compete against Digital. So she turned the contract down. Bill Gates went elsewhere, eventually coming up with a program called DOS, the software that put Microsoft on the map.

No comments:

Post a Comment