BACKGROUND

The trouble at Salem, Massachusetts, began with two young girls acting oddly. It explodes into one of the strangest cases of mass hysteria in American history. In the six-month period between March and September 1692, 27 people were convicted on witchcraft changes; 20 were executed, and more than 100 people were in prison awaiting trial.

CHILD’S PLAY

In March 1692, nine-year-old Betty Parris and her cousin Abigail Williams, 12, were experimenting with a fortune-telling trick they’d learned from Tituba, the Parris family’s West Indian slave. To find out what kind of men they’d marry when they grew up, they put an egg white in a glass… and then studied the shape it made in the glass.

In March 1692, nine-year-old Betty Parris and her cousin Abigail Williams, 12, were experimenting with a fortune-telling trick they’d learned from Tituba, the Parris family’s West Indian slave. To find out what kind of men they’d marry when they grew up, they put an egg white in a glass… and then studied the shape it made in the glass.But instead of glimpsing their future husbands, the girls saw an image that appeared to be “in the likeness of a coffin.” The apparition shocked them… and over the next few days they exhibited behavior that witnesses described as “foolish, ridiculous speeches,” “odd postures,” “distempers,” and “fits.”

Reverend Samuel Parris was startled by his daughter’s condition and took her to see William Griggs, the family doctor. Griggs couldn’t find out what was wrong with the girl, but he suspected the problem had supernatural origins. He told Rev Parris that he thought the girl had fallen victim to “the Evil Hand” -witchcraft.

The family tried to keep Betty’s condition a secret, but rumors began spreading almost immediately -and within two months at least eight other girls began exhibiting similar forms of bizarre behavior.

THE PARANOIA GROWS

The citizens of Salem Village demanded that the authorities take action. The local officials subjected the young girls to intense questioning, and soon the girls began naming names. The first three women they accused of witchcraft were Tituba and two other women from Salem Village, Sarah Good and Sarah Osborne.

The three women were arrested and held for questioning. A few weeks later two more suspects, Martha Cory and Rebecca Nurse, were arrested on similar charges. And at the end of April a sixth person -the Reverend George Burroughs, a minister that Abigail Williams identified as the leader of the witches- was arrested and imprisoned. The girls continued to name names. By the middle of May, more than 100 people had been arrested for witchcraft.

THE TRIALS

On May 14, 1692, the newly appointed governor, Sir William Phips, arrived from England. He immediately set up a special court, the Court of Oyer and Terminer, to hear the witchcraft trials that were clogging the colonial legal system.

On May 14, 1692, the newly appointed governor, Sir William Phips, arrived from England. He immediately set up a special court, the Court of Oyer and Terminer, to hear the witchcraft trials that were clogging the colonial legal system.* The first case heard was that against Bridget Bishop. She was quickly found guilty of witchcraft, sentenced to death, and hung on June 10.

* On June 19 the court met a second time, and in a single day heard the cases of five accused women, found them all guilty, and sentenced them to death. They were hung on July 19.

* On August 5 the court heard six more cases, and sentenced all six women to death. One woman, Elizabeth Proctor, was spared because she was pregnant- and the authorities did not want to kill an innocent life along with a guilty one. The remaining five women were executed on August 19.

* Six more people were sentenced to death in early September. (Only four were executed: one person was reprieved, and another woman managed to escape from prison with the help of friends.) The remaining sentences were carried out on September 22.

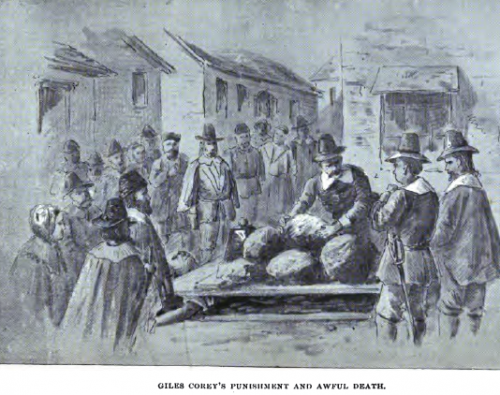

*Two days later, the trials claimed their last victim when Giles Cory, an accused wizard, was executed by “pressing” (he was slowly crushed to death under heavy weights) after he refused to enter a plea.

REVERSAL OF FORTUNE

By now the hysteria surrounding the witch trials was at its peak: 19 accused “witches” had been hung, about 50 had “confessed” in exchange for lenient treatment, more than 100 people accused of witchcraft were under arrest and awaiting trial -and another 200 people had been accused of witchcraft but had not yet been arrested. Despite all this, the afflicted girls were still exhibiting bizarre behavior. But public opinion began to turn against the trials. Community leaders began to publicly question the methods that the courts used to convict suspected witches. The accused were denied access to defense counsel, and were tried in chains before jurors who had been chosen from church membership lists. The integrity of the girls then came into question. Some of the adults even charged that they were faking their illnesses and accusing innocent people for the fun of it. One colonist even testified later that one of the bewitched girls had bragged to him that “she did it for sport.”

The integrity of the girls then came into question. Some of the adults even charged that they were faking their illnesses and accusing innocent people for the fun of it. One colonist even testified later that one of the bewitched girls had bragged to him that “she did it for sport.”As the number of accused persons grew into the hundreds, fears of falling victim to witchcraft were replaced by an even greater fear: that of being falsely accused of witchcraft. The growing opposition to the proceedings came from all segments of society: common people, ministers -even from the court itself.

THE AFTERMATH

Once the tide had turned against the Salem witchcraft trials, many of the participants themselves began having second thoughts. Many of the jurors admitted their errors, witnesses recanted their testimony, and one judge on the Court of Oyer and Terminer, Samuel Sewall, publicly admitted his error on the steps of the Old South Church in 1697. The Massachusetts legislature made amends as well: in 1711 it reversed all of the convictions issued by the Court of Oyer and Terminer (and did it a second time in 1957), and it made financial restitution to the relatives of the executed, “the whole amount unto five hundred seventy eight pounds and twelve shillings.”

No comments:

Post a Comment