Photographers are recognized for capturing the year's best after-dark pictures.

Also: Inside the ER at Mt. Everest

Every spring, many thousands of Westerners travel high in the Himalayas to climb Everest and other mountains. Because of them, many thousands of Nepalese work to guide them, carry their belongings, and build facilities for the tourists -all at altitudes at which people do not normally live. Dr. Luanne Freer established a medical clinic at Everest Base Camp in 2003 to address the health issues that come with high-altitude tourism. Not only was the base camp area lacking medical expertise, but local people who worked in the tourism industry (and could not pay for care) were being ignored elsewhere.

Every spring, many thousands of Westerners travel high in the Himalayas to climb Everest and other mountains. Because of them, many thousands of Nepalese work to guide them, carry their belongings, and build facilities for the tourists -all at altitudes at which people do not normally live. Dr. Luanne Freer established a medical clinic at Everest Base Camp in 2003 to address the health issues that come with high-altitude tourism. Not only was the base camp area lacking medical expertise, but local people who worked in the tourism industry (and could not pay for care) were being ignored elsewhere.The ER’s locale might be glamorous, but the work is often not. Headaches, diarrhea, upper respiratory infections, anxiety and ego-related issues disguised as physical ailments are the clinic’s daily bread and butter. And although the clinic’s resources have expanded dramatically over the past nine years, there is no escaping the fact that this is a seasonal clinic housed in a canvas tent located at 17,590 feet. When serious incidents do occur, Freer and her colleagues must problem solve with a severely limited toolbox. Often the handiest implement is duct tape.Read more about Dr. Freer and she clinic she established at Smithsonian.

“There is no rule book that says, ‘When you’re at 18,000 feet and this happens, do x.’ Medicine freezes solid, tubing snaps in the icy winds, batteries die—nothing is predictable,” says Freer. But it’s that challenge that keeps Freer and many of her colleagues coming back. This back-to-basics paradigm also engenders a more old-fashioned doctor-patient relationship that Freer misses when practicing in the States.

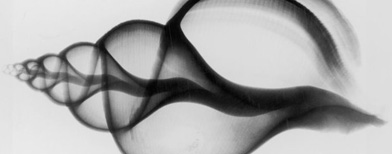

The stunning technology reveals a world that's creepy, beautiful, and not always medical.

Also:

No comments:

Post a Comment