If you've read anything in the past week about ENCODE—a group of laboratories that recently published their latest work on the human genome—then you need to read John Timmer's excellent piece over at Ars Technica.

What ENCODE has actually done, and why it matters, has been widely misrepresented in the mainstream press—largely because of misleading press releases put out by ENCODE, itself. Timmer sets the record straight. It's a long read, but a fascinating one. Highly recommended.

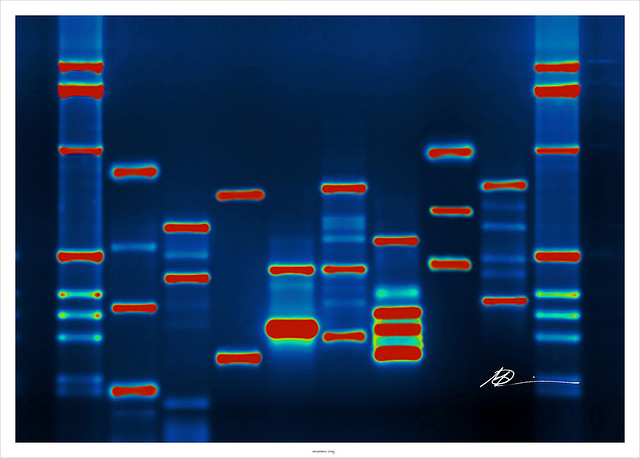

This week, the ENCODE project released the results of its latest attempt to catalog all the activities associated with the human genome. Although we've had the sequence of bases that comprise the genome for over a decade, there were still many questions about what a lot of those bases do when inside a cell. ENCODE is a large consortium of labs dedicated to helping sort that out by identifying everything they can about the genome: what proteins stick to it and where, which pieces interact, what bases pick up chemical modifications, and so on. What the studies can't generally do, however, is figure out the biological consequences of these activities, which will require additional work.Read the rest of John Timmer's story at Ars Technica

Yet the third sentence of the lead ENCODE paper contains an eye-catching figure that ended up being reported widely: "These data enabled us to assign biochemical functions for 80 percent of the genome." Unfortunately, the significance of that statement hinged on a much less widely reported item: the definition of "biochemical function" used by the authors.

This was more than a matter of semantics. Many press reports that resulted painted an entirely fictitious history of biology's past, along with a misleading picture of its present. As a result, the public that relied on those press reports now has a completely mistaken view of our current state of knowledge (this happens to be the exact opposite of what journalism is intended to accomplish). But you can't entirely blame the press in this case. They were egged on by the journals and university press offices that promoted the work—and, in some cases, the scientists themselves.

No comments:

Post a Comment