More than three centuries after the end of the Salem witch trials, they continue to defy explanation. In the mid 1970s, a college undergraduate developed a new theory. Does it hold water? Read on and decide for yourself.

SEASON OF THE WITCH

In the bleak winter of 1692, the people of Salem, Massachusetts, hunkered down in their cabins and waited for spring. It was a grim time: There was no fresh food or vegetables, just dried meat and roots to eat. Their mainstay was the coarse bread they baked from the rye grain harvested in the fall.

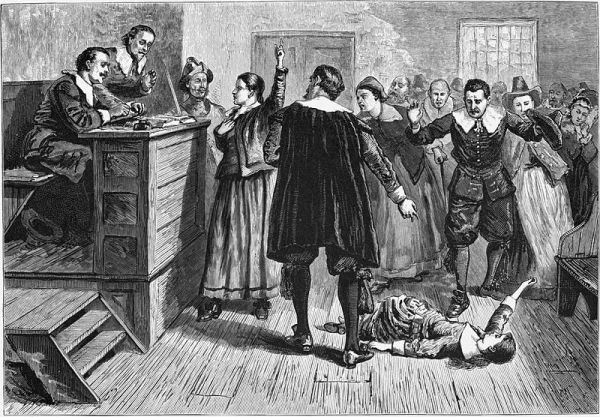

Shortly before the New Year, the madness began. Elizabeth Parris, the 9-year-old daughter of the local preacher, and her cousin, 11-year-old Abigail Williams, suffered from violent fits and convulsions. They lapsed into incoherent rants, had hallucinations, complained of crawly sensations on their skin, and often retreated into dull-eyed trances. Their desperate families turned to the local doctor, who could find nothing physically wrong with them. At his wit's end, he decided there was only one reasonable explanation: witchcraft.

BLAME GAME

Word spread like wildfire through the village: an evil being was hexing the children. Soon, more "victims" appeared, most of them girls under the age of twenty. The terrified villagers started pointing the finger of blame, first at an old slave named Tituba, who belonged to Reverend Parris, then to old women like Sarah Good and Sarah Osborn. The arrests began on February 29; the trials soon followed. That June, 60-year-old Bridget Bishop was the first to be declared guilty of witchcraft and the first to hang. By September, 140 "witches" had been arrested and 19 had been executed. Many of the accused barely escaped the gallows by running into the woods and hiding. Then, sometime over the summer, the demonic fits stopped -and the frenzy of accusation and counter-accusation stopped with them. As passions cooled, the villagers tried to put their community back together again.

UNANSWERED QUESTIONS

What happened to make these otherwise dour Puritans turn on each other with such destructive frenzy? Over the centuries several theories have been put forth, from the Freudian -that the witch hunt was the result of hysterical tension resulting from centuries of sexual repression- to the exploitive- that it was fabricated as an excuse for a land grab (the farms and homes of all the victims and many of the accused were confiscated and redistributed to other members of the community). But researchers had never been able to find real evidence to support these theories. Then in the 1970s, a college student in California made a deduction that seemed to explain everything.

Linnda Caporael, a psychology major at U.C. Santa Barbara, was told to choose a subject for a term paper in her American History course. Having just seen a production of Arthur Miller's play The Crucible (a fictional account of the Salem trials), she decided to write about the witch hunt. "As I began researching," she later recalled, "I had one of those 'a-ha!' experiences." The author of one of her sources said he remained at a loss to explain the hallucinations of the villagers of Salem. "It was the word 'hallucinations' that made everything click," said Caporael. Years before, she'd read of a case of ergot poisoning in France where the victim had suffered from hallucinations, and she thought there might be a connection.

THE FUNGUS AMONG US

(Image credit: Flickr user Jasja Dekker)

(Image credit: Flickr user Jasja Dekker)They were. Ergot needs warm, damp weather to grow, and those conditions were rife in the fields around Salem in 1691. Rye was the primary grain grown, so there was plenty of it to be infected. Caporael also discovered that most of the accusers lived on the west side of the village, where the fields were chronically marshy, making them a perfect breeding ground for the fungus. The crop harvested in the fall of 1691 would have been baked and eaten during the following winter, which was when the fits of madness began. However, the next summer was unusually dry, which could explain the sudden drop in the bewitchments. No ergot, no madness.

SHE RESTS HER CASE

Caporael continued to research her theory as she pursued her Ph.D., publishing her findings in 1976 in the journal Science, which brought her support from the scientific community and attention from the news media. Caporael had been careful to say that her theory only accounts for the initial cause of the Salem witch hunts. As the frenzy grew in scope and consequence, she's convinced that the actual sequence of events probably included not only real moments of mass hysteria but also some overacting on the part of the accusers (motivated as much by fear of being accused themselves as by any actual malice toward the accused).

OTHER POSSIBILITIES

Caporael's theory remains one of the most convincing explanations for what started the madness that tore apart the village of Salem, Massachusetts, in 1692 …but there are others.

* Encephalitis Lethargica. Historian Laurie Win Carlson compared the symptoms of the accused in Salem (violent fits trance or coma-like states) with those experienced by victims of an outbreak of Encephalitis Lethargica, an acute inflammation of the brain, between 1915 and 1926. The trials were likely a "response to unexplained physical and neurological behaviors resulting from an epidemic of encephalitis," she says.

* Jimson Weed. This toxic weed, sometimes called devil's trumpet or locoweed, grows wild in Massachusetts. Ingesting it can cause hallucinations, delirium, and bizarre behavior.

No comments:

Post a Comment