The

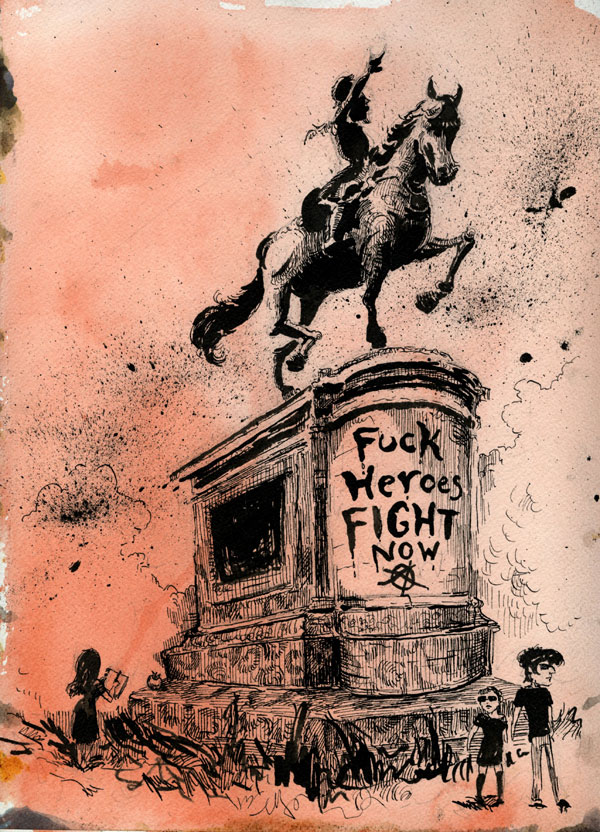

Golden Dawn used to come out only at night. For a street-fighting

fascist gang turned ascendant political party, with all the weary

symbolism of flame-waving and puffed-up synchronized shouting,

individual members of Greece's ultra-right thug club were curiously

reticent to attack immigrants and people of color before

nightfall—until now. Now, they’re killing in daylight.

The

Golden Dawn used to come out only at night. For a street-fighting

fascist gang turned ascendant political party, with all the weary

symbolism of flame-waving and puffed-up synchronized shouting,

individual members of Greece's ultra-right thug club were curiously

reticent to attack immigrants and people of color before

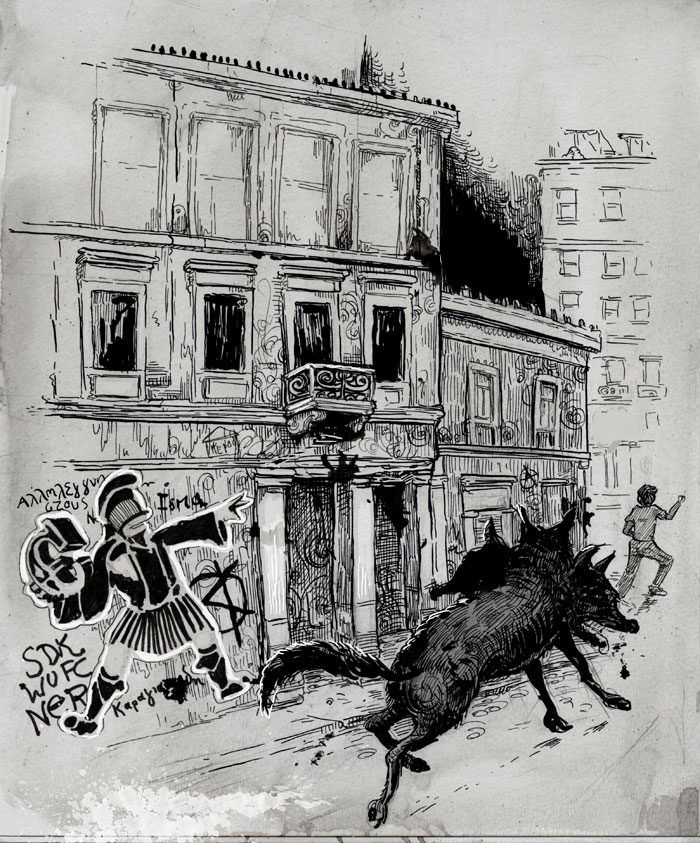

nightfall—until now. Now, they’re killing in daylight.They come out in clutches of three, four or more and attack in the streets, usually under the cover of darkness. But lately they have been growing bolder, emerging during the daytime, in full view of a police force that nobody trusts to intervene. Many areas of Athens have become, in the past year, suspended street-battles. People with darker skin are afraid to go out alone.

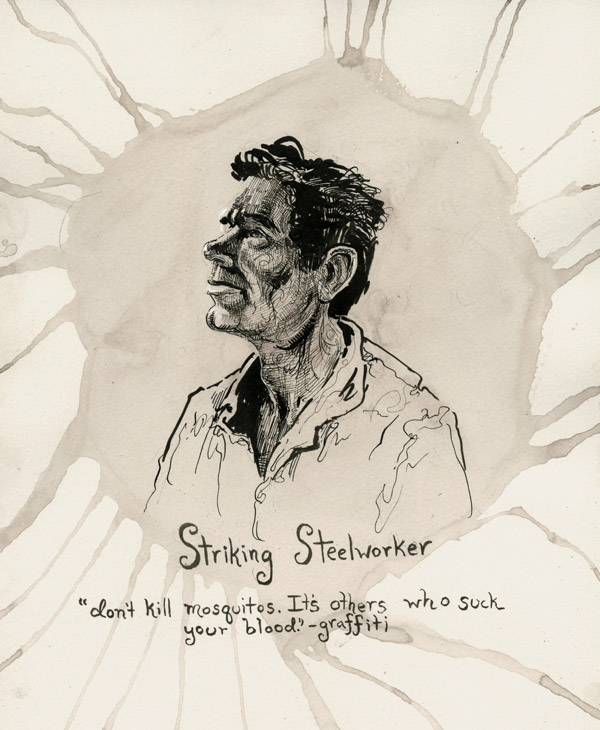

“I came here from Bangladesh six and a half years ago, and in the last two years a lot has changed,” says Arif, 28, a marketing student living in central Athens. While racist violence was a sporadic problem, “Now the Golden Dawn come out in large numbers and openly, they have public meetings, speeches saying we don’t want immigrants in our country, and they beat up people right in front of the police, who do nothing,” he says. Arif is shy and slight, stacking chairs in the restaurant where he works, but as he describes what it is like to be Asian in Greece, he slams the chairs down hard and speaks louder.

“For sure, I’ve been afraid,” he says. “When I first came here, I was going out almost every day and coming back at two or three in the morning, but now those groups are bigger. They draw their marks around Attica Square. They’re not afraid of anyone.”

Omonia is a poor area of central Athens where refugees and migrants arriving from ports across the country concentrate. They are no more able to find livable work than any native Greek. It’s where the police raids have started, where the worst of the racist violence takes place after dark. And yet, according to New Democracy officials, it is the ordinary citizens of Omonia who are the real problem.

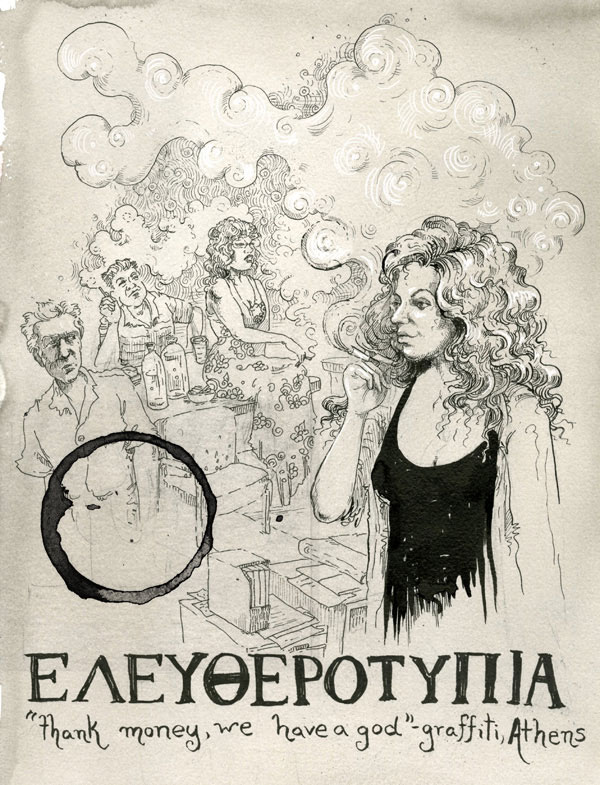

One soon suspects that New Democracy, Greece's main center-right party, sees political advantage in fostering racial tension and allowing violence towards migrants to continue. When you learn that international human rights organisations condemned Greek police for letting racist attacks go unpunished, even as 1,600 migrants were deported in the first of many public raids, the suspicion becomes nauseating reality. The new deportation policy is named for Zeus Xenios—the Greek god of hospitality—because we have come to the end of the age of irony. These days, state power is the bully in the corner, daring you to laugh in its face.

Thanks in part to its defenders in the police force, the Golden Dawn won 18 seats at the last elections with an agenda openly hostile to migrants and people of color. It pursues the standard route for far-right extremist groups seeking to exploit economic hardship in Europe: appeals to nostalgia and patriotism combined with a scantily-clad agenda of violence.

"I know many [who have been attacked by Golden Dawn members]" says Malick Abdul, a middle-aged Pakistani community leader in Nikaea. "Only a month ago there was a case where seventeen people were beaten in a bus station. The bus driver and steward, after dragging them off the bus, called Golden Dawn and they all attacked the group of Pakistanis. This happened in Pyrgos. I’ve been in Greece for 23 years now and it wasn’t like this before. We were having a wonderful time here. But in the last 4 years the atmosphere changed and things like that started happening. I have a shop here. My children were born here."

"The police don't come here anymore," Malick continues. "They just stopped. Buses, as well. They attack us everyday, even today, just before the demonstration. And the police blocked all the buses that were coming to bring more people to the demo from around Athens. All the streets were blocked, and the buses were turned around."

"I was attacked and stabbed here, about a year ago." says another man, interrupting him, "It was a group of seven. Golden Dawn."

Two hours before dusk, the speeches end and the march sets off. The streets are narrow, the tarmac coated in hot dust. The demonstrators, chanting in unison, pour down a throughway. It's the same chant, over and over—pote ksana fasismos!—fascism, never again. Not just never, but never again. In continental Europe, in a suburb where the grandmothers leaning over balconies to watch the drama have clear and potent memories of the 1967–1974 military junta, the distinction is important.

No comments:

Post a Comment