The bacterial zoo inside your gut could look very different if you're a vegetarian or an Atkins dieter, a couch potato or an athlete, fat or thin.

Now for a fee — $69 and up — and a stool sample, the curious can find out just what's living in their intestines and take part in one of the hottest new fields in science.

Wait a minute: How many average Joes really want to pay for the privilege of mailing such, er, intimate samples to scientists?

A lot, hope the researchers running two novel citizen-science projects.

One, the American Gut

Project, aims to enroll 10,000 people — and a bunch of their dogs and

cats too — from around the country. The other, uBiome, separately aims

to enroll nearly 2,000 people from anywhere in the world.

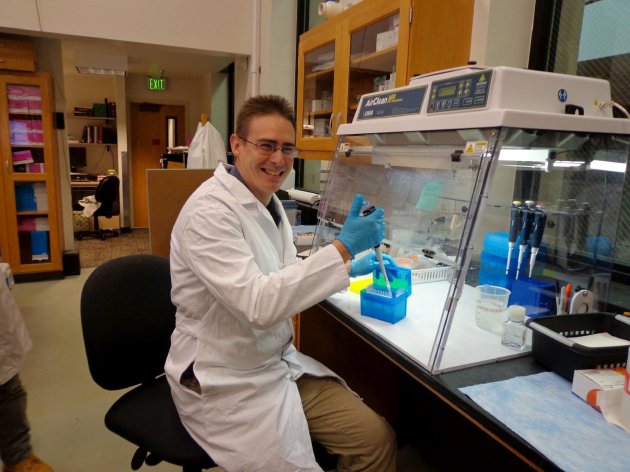

"We're finally enabling people to realize the power and value of

bacteria in our lives," said microbiologist Jack Gilbert of the

University of Chicago and Argonne National Laboratory. He's one of a

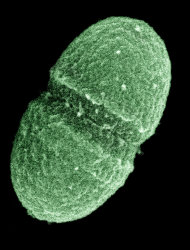

team of well-known scientists involved with the American Gut Project.Don't be squeamish: Yes, we share our bodies with trillions of microbes, living communities called microbiomes. Many of the bugs, especially those in the intestinal tract, play indispensable roles in keeping us healthy, from good digestion to a robust immune system.

But which combinations of bacteria seem to keep us healthy? Which ones might encourage problems like obesity, diabetes or irritable bowel syndrome?

And do diet and lifestyle affect those microbes in ways that we might control someday?

Answering those questions will

require studying vast numbers of people. Getting started with a

grassroots movement makes sense, said National Institutes of Health

microbiologist Lita Proctor, who isn't involved with the new projects

but is watching closely.

After all, there was much interest in the taxpayer-funded Human

Microbiome Project, which last summer provided the first glimpse of what

makes up a healthy bacterial community in a few hundred volunteers.Proctor, who coordinated that project, had worried "there would be a real ick factor. That has not been the case," she said. Many people "want to engage in improving their health."

Scott Jackisch, a computer consultant in Oakland, Calif., ran across American Gut while exploring the science behind different diets, and signed up last week. He's read with fascination earlier microbiome research: "Most of the genetic matter in what we consider ourselves is not human, and that's crazy. I wanted to learn about that."

Testing a single stool sample costs $99 in that project, but he picked a three-sample deal for $260 to compare his own bacterial makeup after eating various foods.

"I want to be extra, extra well," said Jackisch, 42. Differing gut microbes may be the reason "there's no one magic bullet of diet that people can eat and be healthy."

It's clear that people's gut bacteria

can change over time. What this new research could accomplish is a

first look at how different diets may play a role, "a much better

understanding of what matters and what doesn't," said American Gut lead

researcher Rob Knight of the University of Colorado, Boulder.

"We don't just want people that have a gut-ache. We want couch

potatoes. We want babies. We want vegans. We want athletes. We want

anybody and everybody because we need that complete diversity," added

American Gut co-founder Jeff Leach, an anthropologist.One challenge is making sure participants don't expect that a map of their gut bacteria can predict their future health, or suggest lifestyle changes, anytime soon.

"I understand I'm not going to be able to say, 'Oh, my gosh, I'll be susceptible to this,'" said Bradley Heinz, 26, a financial consultant in San Francisco. He is paying uBiome $119 to analyze both his gut and mouth microbiomes; just the gut is $69.

"The more people that participate, the more information comes out and the more that everybody benefits," he added.

Participants can sign up for

either project via the social fundraising site Indiegogo.com over the

next month. They also can send scrapings from the skin, mouth and other

sites, to analyze that bacteria. Sign up enough family members or body

sites, or be tracked over time, and the price can rise into the

thousands. American Gut researchers plan some free testing for those who

can't afford the fees, to increase the experiment's diversity.

Don't forget the pets: "We sleep

with them, play with them, they often eat our food," Leach said. What

bacteria we have in common is the next logical question.

Already, American Gut researchers

are preparing to compare what they find in the typical U.S. gut with a

few hundred people in rural Namibia, who eat what's described as

hunter-gatherer fare. Also, Leach will spend three months living in

Namibia next year, and is storing his own stool samples for

before-and-after comparison.

But diet isn't the only factor.

Your bacterial makeup starts at birth: Babies absorb different microbes

when they're born vaginally than when they're born by C-section, a

possible explanation for why cesareans raise the risk for certain

infections. Taking antibiotics alters this teeming inner world, and it's

not clear if there are lasting consequences, especially for young

children.

Then there's your environment,

such as the infections spread in hospitals. In February, a new

University of Chicago hospital building opens and Gilbert will test the

surfaces, the patients and their health workers to see how quickly bad

bugs can move in and identify which bacteria are protective.

Whatever the findings, all the research marks "a huge teachable moment" about how we interact with microbes, Leach said.

No comments:

Post a Comment