Paris

If you think the streets of Paris are enchanting, wait till you discover what lurks below.

THEY DUG PARIS

Most visitors to Paris have no idea that beneath the City of Light is a dark labyrinth of branching tunnels and abandoned quarries. Paris sits atop massive limestone and gypsum formations that have been quarried for more than a thousand years. The Romans chiseled the fine-grained limestone into bathhouses and sculptures. The French used it to build thousands of buildings, everything from Notre Dame cathedral and the Louvre Museum to Paris Police Headquarters. As for the gypsum, ever heard of plaster of Paris? That's where it comes from.

When the mining started, the quarries were outside of town, but over the centuries the city spread and so did the quarries. Eventually Paris ended up with a 1,900-acre underground maze that starts about 15 feet below the streets and ends 120 feet underground. Parisians call the multi-level maze gruyère (Swiss cheese), and that's exactly what a cross-section of the ground beneath their feet looks like.

THAT SINKING FEELING

When an entire city ends up on holey ground, things get shaky. Residents got their first glimpse of how unstable their city had become in 1774, when one of the tunnels collapsed, gulping down houses and people along Rue d'Enfer (Hell Street). Parisians panicked, so Louis XVI created the Inspection Generale des Carrieres (quarry inspectors) and appointed architect Charles-Axel Guillaumot as its first chief. He instructed Guillaumot to do three things: 1) find all the empty spaces under Paris, 2) make a map of them, and 3) reinforce any spaces below public streets or below buildings belonging to the king. Personally inspecting the sinkholes to a depth of more than 75 feet, Guillaumot was horrified by what he found and told Louis the truth: "The temples, palaces, houses, and public streets of several parts of Paris and its surroundings are about to sink into giant pits."

MOLD LANG SYNE

That wasn't the only problem in Paris. Thanks to war, famine, and plague, the city's cemeteries were full to overflowing. One frosty February morning in 1788, a homeowner started down to his cellar but was immediately driven back upward by a terrible stench. Egged on by his neighbors (and wearing a vinegar-soaked handkerchief over his nose), he crept back down and found 20 decaying bodies, covered in graveyard mold, bursting through the wall. The graveyards had finally gone beyond their limits.

When an entire city ends up on holey ground, things get shaky. Residents got their first glimpse of how unstable their city had become in 1774, when one of the tunnels collapsed, gulping down houses and people along Rue d'Enfer (Hell Street). Parisians panicked, so Louis XVI created the Inspection Generale des Carrieres (quarry inspectors) and appointed architect Charles-Axel Guillaumot as its first chief. He instructed Guillaumot to do three things: 1) find all the empty spaces under Paris, 2) make a map of them, and 3) reinforce any spaces below public streets or below buildings belonging to the king. Personally inspecting the sinkholes to a depth of more than 75 feet, Guillaumot was horrified by what he found and told Louis the truth: "The temples, palaces, houses, and public streets of several parts of Paris and its surroundings are about to sink into giant pits."

MOLD LANG SYNE

That wasn't the only problem in Paris. Thanks to war, famine, and plague, the city's cemeteries were full to overflowing. One frosty February morning in 1788, a homeowner started down to his cellar but was immediately driven back upward by a terrible stench. Egged on by his neighbors (and wearing a vinegar-soaked handkerchief over his nose), he crept back down and found 20 decaying bodies, covered in graveyard mold, bursting through the wall. The graveyards had finally gone beyond their limits.

But

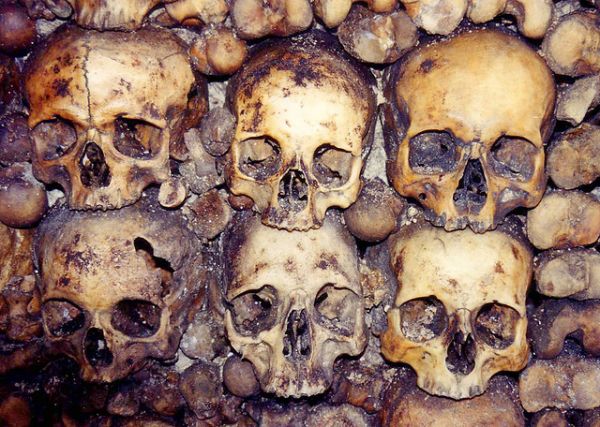

where others saw a problem, King Louis saw an opportunity. He closed

the cemeteries and had the bones dug up and stacked into the quarries.

Six million skeletons -mounds and stacks of skulls, tibias, femurs, and

spines- turned the chambers into catacombs, an underground boneyard that

became known as "The Empire of the Dead."

CATS IN A MAZE

As Paris grew, the gruyère got even more full of holes. Cults dug crypts. City engineers built aqueducts, sewers, water mains, and tunnels for Métro lines. They dug conduits for telephone and electrical lines, bunkers for shelter during World War II, and garages for underground parking. And at the very bottom: the ancient quarries, their ceilings braced by nothing but limestone pillars and stacked stones.

Of the 180 miles of tunnels maintained by the Inspection Generale des Carrieres (IGC), only one mile -the catacombs- is open to the public. That doesn't stop the cataphiles. After dark, these hardcore cavers scurry down drains and through ventilation shafts. They chisel open manhole covers and sneak through entrances in hospital basements, the cellars of bars, church crypts, and subway tunnels. Why? "At the surface there are too many rules," says one cataphile. "Here we do what we want."

CATS IN A MAZE

As Paris grew, the gruyère got even more full of holes. Cults dug crypts. City engineers built aqueducts, sewers, water mains, and tunnels for Métro lines. They dug conduits for telephone and electrical lines, bunkers for shelter during World War II, and garages for underground parking. And at the very bottom: the ancient quarries, their ceilings braced by nothing but limestone pillars and stacked stones.

Of the 180 miles of tunnels maintained by the Inspection Generale des Carrieres (IGC), only one mile -the catacombs- is open to the public. That doesn't stop the cataphiles. After dark, these hardcore cavers scurry down drains and through ventilation shafts. They chisel open manhole covers and sneak through entrances in hospital basements, the cellars of bars, church crypts, and subway tunnels. Why? "At the surface there are too many rules," says one cataphile. "Here we do what we want."

While preparing an article for National Geographic,

reporter Neil Shea got an inside look at what cataphiles do

underground. Some carry scuba tanks for exploring and mapping abandoned

wells. Some create art, such as a four-foot-high limestone castle

complete with drawbridge, moat, towers, and even a little LEGO soldier

guarding the gate. Other host events: An author and an illustrator

staged a book signing for their graphic novel Le Diable Vert (The Green Devil).

A group of people held a banquet, their candelabra casting shadows

across the stone table as they dipped into cheese fondue and listened to

chamber music. With cataphiles scurrying through the gruyère like mice, the city decided to hire another kind of cat to hunt them down.

ON THE PURR-ROWL

ON THE PURR-ROWL

"We

believe deeply that the catacombs belong to us, and that no one has a

right to take them away," says a longtime cataphile nicknamed Morthicia.

The cataflics disagree. These special cops patrol the maze,

chase offenders from their underground lairs, and hand out fines. That's

business as usual… unless they stumble upon something unexpected.

In 2004, during a training exercise 50 feet below the surface, officers moved a tarp marked "Building site. No access." That triggered a tape recording of dogs barking. "To frighten people off," said an officer. Beyond the barking they found 3,000 square feet of subterranean galleries. In one gallery there was theater seating for 20 (carved into the rock), a full-size movie screen, and projection equipment, along with all kinds of films, from 1950s film noir classics to contemporary thrillers. In another room, they found tables and chairs, and a well-stocked bar. Three days later, they returned with an electrician to trace the wires being used to pirate power and phone service. But the galleries had been stripped; not a bit remained to offer a clue to the culprits. All that was left was a note in the middle of the floor: "Do not try to find us."

CHEESY PARISEE

In 2004, during a training exercise 50 feet below the surface, officers moved a tarp marked "Building site. No access." That triggered a tape recording of dogs barking. "To frighten people off," said an officer. Beyond the barking they found 3,000 square feet of subterranean galleries. In one gallery there was theater seating for 20 (carved into the rock), a full-size movie screen, and projection equipment, along with all kinds of films, from 1950s film noir classics to contemporary thrillers. In another room, they found tables and chairs, and a well-stocked bar. Three days later, they returned with an electrician to trace the wires being used to pirate power and phone service. But the galleries had been stripped; not a bit remained to offer a clue to the culprits. All that was left was a note in the middle of the floor: "Do not try to find us."

CHEESY PARISEE

A group calling itself "La Mexicaine De Perforation"

later claimed responsibility for the theater. "There are a dozen more

where that one came from," said Patrick Saletta, a photographer who

documents the urban underground. "You guys have no idea what's down

there." Perhaps not, but here's something they do know:

Inspector Guillaumot's 18th-century warning is still valid. In 1961 the

maze swallowed an entire south side neighborhood. Small collapses happen

every year, yet Parisians seem unconcerned. They have the IGC -still

vigilant more than 200 years after its founding- to keep the City of

Light from falling into the gruyère.

No comments:

Post a Comment