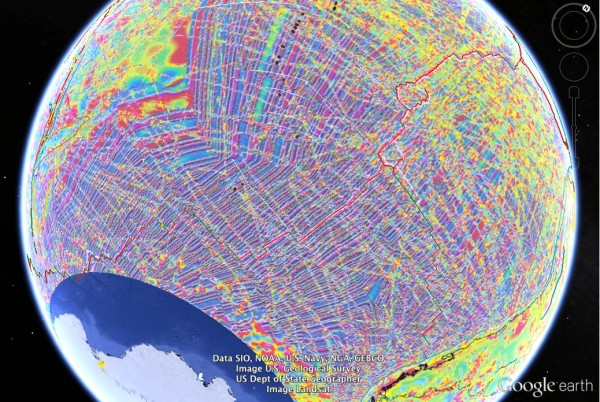

This image shows magnetic anomalies in the South Pacific — underwater

lines where the crust of the Earth either matches up with the planet's

overall magnetic polarity (reds and purples) or is completely reversed

(blues). Invisible to the naked eye, these stripes run along all of

Earth's ocean basins. We first noticed them in the 1950s and, at first,

they were a giant mystery. Why would there be these distinct lines of

magnetism, and why would the lines fluctuate in their polarity? As Chris

Rowan explains at the Highly Allochthonous blog, the answer ended up

being a key part of

proving that chunks of the Earth's crust were moving away from each other.

Fred Vine and Drummond Matthews thought through the

consequences of the hypothesis put forward by Harry Hess, that new

oceanic crust was being continuously produced by the eruption of basalt

at mid-ocean ridges. When combined with the facts that newly cooled

basalt has a strong remanent magnetisation aligned with the ambient

magnetic field, and that the Earth’s magnetic field reverses its

polarity every million years or so. Vine and Matthews* argued that if

seafloor spreading was indeed occurring at mid-ocean ridges, then linear

positive and negative magnetic anomalies, formed from crust produced in

normal and reversed polarity chrons, would form a symmetric pattern

around the mid-ocean ridges, which is exactly what we see.

No comments:

Post a Comment