|

| A giant sloth bone might hold the key to the peopling of the Americas [Credit: Martin Batalles] |

"That's pretty old for a site that has evidence of human presence, particularly in South America," said study co-author Richard Farina, a paleontologist at Uruguay's Universidad de la Republica.

"So, it's strange and unexpected."

Giant sloths, saber-toothed cats, oversize armadillos, and other large mammals once roamed the Americas—a diversity that would easily rival an African savannah today.

But by 11,000 years ago, many of the species had disappeared, likely due to climate change or the arrival of human hunters in the New World. But when exactly humans got here, and how they arrived, remains unknown.

In 1997, severe drought forced local farmers to drain a lagoon in Arroyo del Vizcaino, which exposed a mysterious bed of gigantic bones.

|

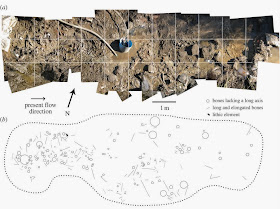

| The giant sloth bones were uncovered at a dig site dated at 29,000 to 30,000 years old [Credit: Martin Batalles] |

Many of the bones belong to three extinct ground sloth species, mainly Lestodon armatus. Weighing in at up to four tons, the animals "were the size of smallish elephants," he said.

Fossils from other common South American megafauna turned up in the mud as well: three species of glyptodonts, or armadillo ancestors; a hippo-like animal called a toxodon, which has no living relatives; a South American saber-toothed cat (Smilodon populator); and an elephant-like stegomastodon, among others.

Some of the bones bear telltale markings of human tools, which suggests the animals were hunted for food. The team also found a potentially human-made scraper that could have been used on dry animal hides, and stone flakes.

Clues from the site point to a human presence at Arroyo del Vizcaino much earlier than accepted theories of migration. Farina and his team are both excited and cautious about their results.

Farina said the strength of the new evidence lies in the team's methodology and the fact that two of the bones they tested for dating also bore markings similar to those made by human tools. "The association can't be closer than it is," he said.

The study certainly does not prove definitively that humans were killing giant sloths 30,000 years ago in South America.

The fossils found at Arroyo del Vizcaino might simply be a product of nature mimicking human tools, and the authors acknowledge that possibility.

"South America played an exceptionally important role in the peopling of the Americas, and I'm pretty sure we have some significant surprises waiting for us," Bonnie Pitblado, an archaeologist at the University of Oklahoma who was not associated with the study, said in an email.

"Maybe people killing sloths at [the Arroyo del Vizcaino site] 30,000 years ago is one of them, maybe it's not—but it certainly isn't going to hurt to have it on our collective radar screen as we continue to contemplate the peopling of the New World."

The Uruguayan team has further excavations and environmental reconstruction studies planned for the site.

Farina estimates that it could yield a thousand more bones, and they plan to build a local museum to house the site's many fossils.

No comments:

Post a Comment