Necessary and right, or bad for democracy?

by Chris Nichols

The time has come to end presidential term limits, because continuing the restrictions on how long one can serve in the country's highest office is bad for the United States, a university professor argued this week.

In an opinion piece published in the Washington Post, Jonathan Zimmerman, a history and education professor at New York University, says deciding whether a president deserves a third, fourth or more terms should be left to the American people, not the 22nd Amendment to the Constitution, which placed a two-term limit on the position. As background, here's an excerpt from the amendment, ratified in 1951:

"No

person shall be elected to the office of the President more than twice,

and no person who has held the office of President, or acted as

President, for more than two years of a term to which some other person

was elected President shall be elected to the office of the President

more than once."In an opinion piece published in the Washington Post, Jonathan Zimmerman, a history and education professor at New York University, says deciding whether a president deserves a third, fourth or more terms should be left to the American people, not the 22nd Amendment to the Constitution, which placed a two-term limit on the position. As background, here's an excerpt from the amendment, ratified in 1951:

The amendment came into being a few years after Franklin Roosevelt

was elected to the fourth of his White House terms. Known to Americans

as the president during the final years of the Great Depression and most

of World War II, Roosevelt, a Democrat, died in office before

completing his last term. After the war, repugicans made a successful

bid to install a two-term maximum for future presidents. But, according

to Zimmerman, they limited not only the president's time in office, but

also "democracy itself."

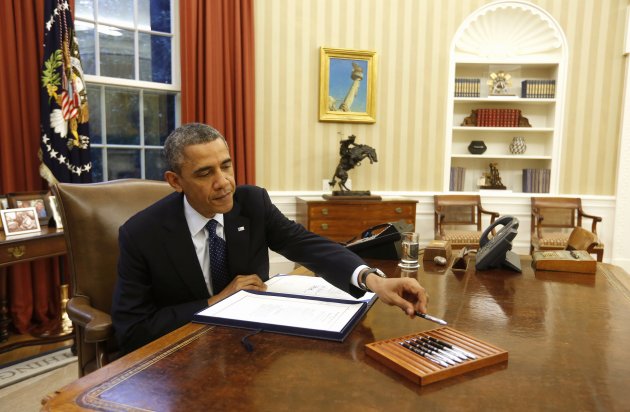

With President Obama's job-approval numbers

down sharply, Zimmerman indicates that the nation's chief executive is

perhaps being hampered by the fact that he's in his final term, giving repugican opponents and even Democrats little incentive to support him on

issues that might hurt their own re-election chances.

To

illustrate his point, he uses two topics in the headlines: the

implemention of the new health care law and the nuclear agreement with

Iran.He writes:

"Many of Obama’s fellow Democrats have distanced themselves from the reform and from the president. Even former president Bill Clinton has said that Americans should be allowed to keep the health insurance they have. Or consider the reaction to the Iran nuclear deal. Regardless of his political approval ratings, Obama could expect repugican senators such as Lindsey Graham (S.C.) and John McCain (Ariz.) to attack the agreement. But if Obama could run again, would he be facing such fervent objections from Sens. Charles Schumer (D-N.Y.) and Robert Menendez (D-N.J.)? Probably not. Democratic lawmakers would worry about provoking the wrath of a president who could be reelected. Thanks to term limits, though, they’ve got little to fear."Zimmerman adds, "Nor does Obama have to fear the voters, which might be the scariest problem of all. If he chooses, he could simply ignore their will. And if the people wanted him to serve another term, why shouldn’t they be allowed to award him one?"

On this last point, he invokes George Washington, the first president of the United States. Washington, he says, stepped down after his second term, but not because he was required by law to do so. Zimmerman says Washington didn't support enforced term limits, citing one of his letters. "I can see no propriety in precluding ourselves from the service of any man who, in some great emergency, shall be deemed universally most capable of serving the public," Washington wrote. By leaving office, however, he did establish a precedent that would be followed for more than a century.

In his "Presidential Term Limits in American History: Power, Principles, and Politics," Michael Korzi, a professor of political science at Towson University, cites the first president's remark, stating that Washington departed voluntarily after his second term "more for personal reasons than for reasons of philosophy."

Even so, the Founding Fathers had different opinions on whether to impose a mandate on term lengths, researchers indicate. (U.S. senators and representatives don't have term limits.) Thomas Jefferson, the third president of the U.S., felt a maximum had merit. In "Jefferson Himself: The Personal Narrative of a Many-Sided American," edited by Bernard Mayo, Jefferson referenced his dislike of the idea of an entrenched leader:

"That I should lay down my charge at a proper season is as much a duty as to have borne it faithfully ... . These changes are necessary, too, for the security of republican government. If some period be not fixed, either by the Constitution or by practice, to the services of the First Magistrate, his office, though nominally elective, will in fact be for life; and that will soon degenerate into an inheritance."

As for the present, Zimmerman's idea isn't new, and in fact, rumor-researching website Snopes.com notes multiple proposals in recent years to repeal the 22nd Amendment. The repugicans and Democrats alike have raised the issue, but none of the attempts have gotten too far. .

No comments:

Post a Comment