Anyone can toilet paper a house or slip a whoopee

cushion onto a chair. Pulling off a truly legendary prank is harder. To

fool the media, crowds, and even the military, you need patience,

planning, and more than a little genius. But when everything comes

together into one big victimless laugh, it’s a thing of beauty. Here

are history’s greatest hoaxes, each one proof that with effort and a

little luck, you can fool a lot of the people, all of the time.

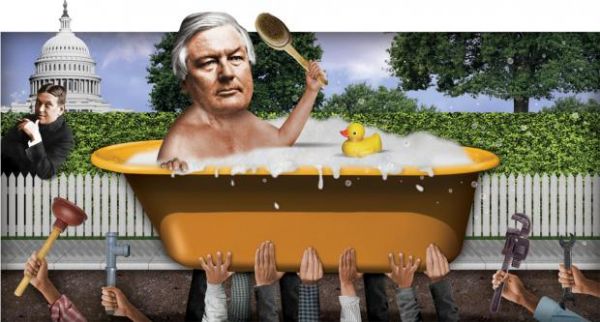

1. The Birth of the Bathtub!

December 20 gets no respect. On the calendar, it’s just another winter day best known for not being Christmas. But in 1917, writer H. L. Mencken set out to change that. When readers of the New York Evening Mail opened the paper in late December, they found Mencken’s 1,800-word essay “A Neglected Anniversary,” detailing the arrival of the bathtub in the United States. Mencken meticulously cataloged the tub’s rocky debut in 1842, explaining how the bathroom fad had caught on only after Millard Fillmore installed one in the White House. By the 20th century, Mencken explained, the momentous anniversary had fallen into obscurity. “Not a plumber fired a salute,” he lamented. “Not a governor proclaimed a prayer.”There’s a good reason why. Mencken had made the whole thing up. The humorist figured everyone would see through the ruse, and he later wrote that the article was “harmless fun” meant to distract readers from World War I. “It never occurred to me it would be taken seriously,” he wrote.

But printing the piece in the Evening Mail gave Mencken’s little joke extra credibility, and he was stunned by how the story snowballed. Within a few years, it had been referenced in “learned journals” and cited “on the floor of Congress.” The tale became so pervasive that the Boston Herald ran an article in 1926 debunking it under the headline "The American Public Will Swallow Anything." Three weeks later, the same paper cited Mencken’s bathtub origin tale as fact.

Mencken tried to set the record straight, but his efforts were futile. People were more interested in hearing about President Fillmore’s tub than hearing the truth. Even today, the nugget resurfaces from time to time: In 2008, the story was featured in a Kia ad, which hailed Fillmore as “best remembered as the first president to have a running water bathtub.” Poor guy can’t even be remembered for something he actually did.

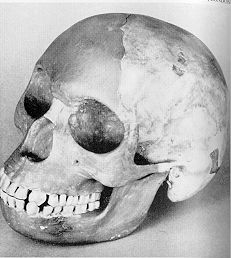

2. Sherlock Holmes Finds the Missing Link

Ever since Darwin published On the Origin of Species,

scientists have been looking for the missing link—a transitional

fossil that would seal the argument for human evolution. In 1912, an

amateur geologist and archaeologist named Charles Dawson found it. The

skull he pulled from a gravel pit in Piltdown, England, seemed to

conclusively fit the part, and the discovery rocked the scientific

community. Skeptics claimed the fossil was exactly what it looked like:

a human skull cobbled together with an ape jaw to fool gullible

scientists. In the ensuing excitement, believers shouted down deniers,

and in December 1912, the Geological Society of London hosted a

ceremony where Dawson presented his fossil, the Piltdown Man.

Ever since Darwin published On the Origin of Species,

scientists have been looking for the missing link—a transitional

fossil that would seal the argument for human evolution. In 1912, an

amateur geologist and archaeologist named Charles Dawson found it. The

skull he pulled from a gravel pit in Piltdown, England, seemed to

conclusively fit the part, and the discovery rocked the scientific

community. Skeptics claimed the fossil was exactly what it looked like:

a human skull cobbled together with an ape jaw to fool gullible

scientists. In the ensuing excitement, believers shouted down deniers,

and in December 1912, the Geological Society of London hosted a

ceremony where Dawson presented his fossil, the Piltdown Man.The doubters continued doubting until 1917, when researchers discovered a similar fossil nearby. The Piltdown faithful were thrilled: the new find, Piltdown II, seemingly legitimized the old one.

But the Piltdown Man’s scientific legitimacy gradually eroded over the next few decades. Other early human skulls began popping up in China and Africa, and each had an apelike skull with a human jaw: the opposite of the Piltdown combo.

The jig was finally up in 1953. After conducting tests on the skull, anthropologist Joseph Weiner and geologist Kenneth Oakley determined Piltdown Man was no man at all. Rather, he was a combination of man (the skull), orangutan (the jaw), and chimp (the teeth). What’s more, fluorine dating showed that the bones were no more than 100,000 years old, certainly not new but not missing-link ancient. The head looked older only because the hoax’s perpetrator had stained it with iron and chromic acid.

While the hoax was eventually exposed, the prankster behind the caper is still at large. Dawson is the most likely culprit, but literary sleuths have turned their suspicions to another man: Sherlock Holmes’s creator, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. Not only was Conan Doyle a member of Dawson’s archaeological society and a frequent visitor to the Piltdown site, he hinted in his novel The Lost World that faking bones is no tougher than forging a photograph—the ultimate smoking gun! If only Holmes were on the case.

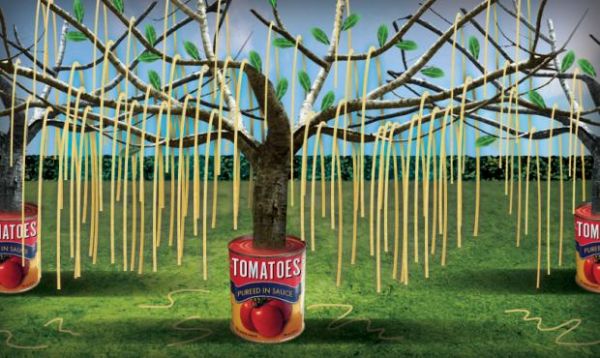

3. Italy’s Secret Pasta Gardens

Viewers ate it up. On April 2 the BBC was flooded with hundreds of phone calls from people eager to grow their own noodles, then a rare treat for British diners. Keeping the whimsy going, the BBC instructed anyone interested in a pasta-bearing tree to “Place a sprig of spaghetti in a tin of tomato sauce and hope for the best.”

4. The World’s Worst Bestseller

Everyone

knows you can’t judge a book by its cover. But the aphorism got an

extra dose of validity in 1969, when Penelope Ashe, a bored Long Island

housewife, wrote the trashy sensation Naked Came the Stranger.

Everyone

knows you can’t judge a book by its cover. But the aphorism got an

extra dose of validity in 1969, when Penelope Ashe, a bored Long Island

housewife, wrote the trashy sensation Naked Came the Stranger.As part of her book tour, Ashe appeared on talk shows and made the bookstore rounds. But Ashe wasn’t what her book jacket claimed. The author was as fictional as the novel she supposedly wrote—and both were the work of Mike McGrady, a Newsday columnist disgusted with the lurid state of the modern bestseller. Instead of complaining, he decided to expose the problem by writing a book of zero redeeming social value and even less literary merit. He enlisted the help of 24 Newsday colleagues, tasking each with a chapter, and instructed them that there should be “an unremitting emphasis on sex.” He also warned that “true excellence in writing will be quickly blue-penciled into oblivion.” Once McGrady had the smutty chapters in hand (which included acrobatic trysts in tollbooths, encounters with progressive rabbis, and cameos by Shetland ponies), he painstakingly edited the prose to make it worse. In 1969, an independent publisher released the first edition of Naked Came the Stranger, with the part of Penelope Ashe played by McGrady’s sister-in-law.

To the journalist’s dismay, his cynical ploy worked. The media was all too fascinated with the salacious daydreams of a “demure housewife” author. And though The New York Times wrote, “In the category of erotic fantasy, this one rates about a C,” the public didn’t mind. By the time McGrady revealed his hoax a few months later, the novel had already moved 20,000 copies. Far from sinking the book’s prospects, the press pushed sales even higher. By the end of the year, there were more than 100,000 copies in print, and the novel had spent 13 weeks on the Times’s bestseller list. As of 2012, the tome had sold nearly 400,000 copies, mostly to readers who were in on the joke. But in 1990, McGrady told Newsday he couldn’t stop thinking about those first sales: “What has always worried me are the 20,000 people who bought it before the hoax was exposed.”

5. Bipedal Beavers, Unicorns, and Other Moon Monsters

Much like submarines, submarine sandwiches, and the U.S. Constitution, the ethics of journalism were still evolving in the early 19th century. One rule that hadn’t totally sunk in yet: Don’t ply your readers with outright fabrications. The newspapers of the day routinely manufactured stories to generate sales, but none was as outrageous as the New York City rag The Sun’s “Great Moon Hoax,” a series of six articles published in 1835 about the discovery of civilization on the moon. The

articles claimed that a British astronomer named John Herschel had

used a powerful new telescope to spot plants, unicorns, bipedal

beavers, and winged humans there. The articles even went a step further,

claiming that our angelic moon brethren collected fruit, built temples

from sapphire, and lived in total harmony. The hoax was debunked

immediately. Soon after the first installment ran in The Sun, its uptown competition, the New York Herald, slammed the story under the headline "The Astronomical Hoax Explained."

The

articles claimed that a British astronomer named John Herschel had

used a powerful new telescope to spot plants, unicorns, bipedal

beavers, and winged humans there. The articles even went a step further,

claiming that our angelic moon brethren collected fruit, built temples

from sapphire, and lived in total harmony. The hoax was debunked

immediately. Soon after the first installment ran in The Sun, its uptown competition, the New York Herald, slammed the story under the headline "The Astronomical Hoax Explained."But the American public preferred a universe dotted with angels, unicorns, and bedazzled architecture. The story created such a buzz that papers around the world rushed to reprint it, while a theater company in New York worked out a dramatic staging. Before long, The Sun was making extra coin selling pamphlets of the whole series and lithographic prints that depicted life on the moon. It took five years for the story’s writer, Richard Adams Locke, to finally confess to making it all up. As he wrote in the New World, his intention was to satirize “theological and devotional encroachments upon the legitimate province of science.” But in all this, the thing we can’t believe is that no New York team has embraced the moon beaver as its mascot.

6. A Math Whiz Horse!

Is

a hoax still a hoax if the perpetrator doesn’t know it? Wilhelm von

Osten would likely say no. At the turn of the 20th century, the German

math teacher was determined to prove the intelligence of animals. After

trying (and failing) to teach a cat and a bear how to add, he finally

found a sufficiently studious beast. With years of training, a horse

named Hans could add, subtract, multiply, and read German.

Is

a hoax still a hoax if the perpetrator doesn’t know it? Wilhelm von

Osten would likely say no. At the turn of the 20th century, the German

math teacher was determined to prove the intelligence of animals. After

trying (and failing) to teach a cat and a bear how to add, he finally

found a sufficiently studious beast. With years of training, a horse

named Hans could add, subtract, multiply, and read German.Von Osten held regular displays of his star pupil’s intelligence. Hans would calculate sums and convert fractions by tapping a hoof to indicate numbers. He became a national sensation, made headlines in the United States, and earned the nickname Clever Hans. To prove that the horse’s skills were real, Von Osten allowed a group of experts to examine his equine genius. They found nothing fishy, and Germany embraced Hans as a marvel until psychology student Oskar Pfungst came along.

Unsatisfied with the work of the experts, Pfungst examined Hans and figured out how the horse was doing its calculator act. Von Osten was sending him subconscious signals. Each time Hans was presented with a math question, he’d tap away until a subtle cue on his owner’s face told him to stop. The cues were so subtle that Von Osten didn’t even know he was giving them. Indeed, the horse got problems right only when they were simple enough for Von Osten to solve, and his percentages plummeted when he wasn’t allowed to face his master. When Pfungst exposed the truth, Von Osten denied it, insisting that Hans really was clever, and he continued to parade his horse before happy crowds. Today, animal psychologists know to write off these cues as the “Clever Hans effect.”

7. The Supergroup That Never Got To Rock

Music fans got exciting news in 1969 when Rolling Stone

reviewed the first album by the Masked Marauders, a supergroup

featuring Bob Dylan, Mick Jagger, John Lennon, and Paul McCartney. Due

to legal issues with their respective labels, the stars’ names wouldn’t

appear on the album cover, but the review extolled the virtues of

Dylan’s new “deep bass voice” and the record’s 18-minute cover songs.

One of the album’s highlights was an extended jam between bass guitar

and piano, with Paul McCartney playing both parts! The writer earnestly

concluded, “It can truly be said that this album is more than a way of

life; it is life.” For anyone paying attention, the absurd details

added up to a clear hoax. The man behind the gag, editor Greil Marcus,

was fed up with the supergroup trend and figured that if he peppered

his piece with enough fabrication, readers would pick up on the joke.

Music fans got exciting news in 1969 when Rolling Stone

reviewed the first album by the Masked Marauders, a supergroup

featuring Bob Dylan, Mick Jagger, John Lennon, and Paul McCartney. Due

to legal issues with their respective labels, the stars’ names wouldn’t

appear on the album cover, but the review extolled the virtues of

Dylan’s new “deep bass voice” and the record’s 18-minute cover songs.

One of the album’s highlights was an extended jam between bass guitar

and piano, with Paul McCartney playing both parts! The writer earnestly

concluded, “It can truly be said that this album is more than a way of

life; it is life.” For anyone paying attention, the absurd details

added up to a clear hoax. The man behind the gag, editor Greil Marcus,

was fed up with the supergroup trend and figured that if he peppered

his piece with enough fabrication, readers would pick up on the joke.They didn’t. After reading the review, fans were desperate to get their hands on the Masked Marauders album. Rather than fess up, Marcus dug in his heels and took his prank to the next level. He recruited an obscure San Francisco band to record a spoof album, then scored a distribution deal with Warner Bros. After a little radio promotion, the Masked Marauders’ self-titled debut sold 100,000 copies. For its part, Warner Bros. decided to let fans in on the joke after they bought the album. Each sleeve included the Rolling Stone review along with liner notes that read, “In a world of sham, the Masked Marauders, bless their hearts, are the genuine article.”

8. How April Fools’ Day Didn’t Get Its Name

As Joseph Boskin would tell you, the origins of April Fools’ are murky. In fact, the Boston University professor and pop culture historian was trying to say just that in a 1983 interview with reporter Fred Bayles. But each time Boskin told Bayles that no one is quite sure how the holiday started, the interviewer pushed him for a more concrete answer. Eventually, the academic got fed up with the aggressive questioning and decided to concoct a story worth printing.Off the top of his head, Boskin began regaling Bayles with a tale from the days when Constantine ruled Rome. Jesters, he said, petitioned the emperor to allow one of their own the chance to rule for just one day. On April 1, Constantine relented. A jester, King Kugel—Boskin named him for the Jewish pudding dish—took over and proclaimed that April 1 would always serve as 24 hours of silliness.

Boskin later said he made the story so absurd that Bayles would have to catch on. No dice. The AP ran Bayles’s story about King Kugel, and soon Boskin was fielding calls from news outlets across the country. He initially kept up the ruse, but a few weeks later, the truth slipped out during one of his lectures about the media’s willingness to believe rumors. The editor of the school paper was in the class, and the campus Daily Free Press ran a headline declaring “Professor Fools AP.”

Once the truth was out, the AP was predictably embarrassed, but the story has a happy ending. Bayles, no longer an eager reporter, is now a professor of journalism at BU, where he can speak from personal experience about the media’s gullibility.

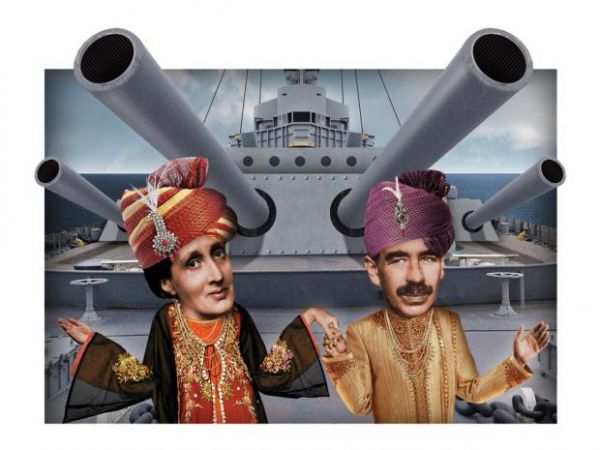

9. Virginia Woolf Ships Out

Before Virginia Woolf and E. M. Forster were literary titans and before John Maynard Keynes was the father of modern economics, they were part of a crowd of friends that informally called themselves the Bloomsbury Group. Comprising writers, artists, and thinkers, the group basically functioned as a fraternity for geniuses. So it’s fitting that the group’s lasting legacy is a piece of tomfoolery. In 1910, the HMS Dreadnought

was the fiercest, strongest ship in the Royal Navy. To the poet

William Horace de Vere Cole, it seemed like the perfect place for the

Bloomsbury Group to stage a high-concept prank. Cole, Woolf, her

brother Adrian Stephen, and three pals decided to sneak aboard the Dreadnought,

disguised as the emperor of Abyssinia and his entourage. Why risk the

wrath of the Royal Navy? Because it was funny! The group sent a phony

telegram to the ship’s commander, letting him know that a delegation

was en route, then they simply showed up at the ship.

In 1910, the HMS Dreadnought

was the fiercest, strongest ship in the Royal Navy. To the poet

William Horace de Vere Cole, it seemed like the perfect place for the

Bloomsbury Group to stage a high-concept prank. Cole, Woolf, her

brother Adrian Stephen, and three pals decided to sneak aboard the Dreadnought,

disguised as the emperor of Abyssinia and his entourage. Why risk the

wrath of the Royal Navy? Because it was funny! The group sent a phony

telegram to the ship’s commander, letting him know that a delegation

was en route, then they simply showed up at the ship.Amazingly, it worked. Dressed in caftans, turbans, and gold chains and with their faces painted black, the “Abyssinians” were welcomed aboard the Dreadnought with an honor guard, a red carpet, and a naval band. Despite the intentionally amateurish costumes, including at least one mustache that began falling off in the rain, the Abyssinians stayed in character for the entire tour. When they spoke, it was either to exclaim “Bunga, bunga!” in excitement or ramble in an invented language of Latin, Swahili, and gobbledygook. At one point, they were forced to decline a meal, relaying through Stephen, who was acting as translator, that the food had not been prepared to their specifications. In reality, they didn’t eat because they were afraid their makeup would come off.

The tour ended without the crew suspecting a thing. But then someone called reporters. British papers had a field day with the story. Sailors were heckled with cries of “Bunga, bunga” in the streets, and King Edward himself made his displeasure with the incident known. In the face of such humiliation, the navy was forced to take action. According to contemporary accounts, the navy got its revenge by caning two of the male hoaxers. Woolf was spared the lash because she was a woman, even though a lady’s mere presence on the ship was one of the greatest sources of the navy’s embarrassment.

Eventually, though, the Royal Navy developed a sense of humor about the incident. When the Dreadnought rammed and sank a German submarine during World War I, its crew received a congratulatory telegram from superiors. The text? “BUNGA BUNGA.”

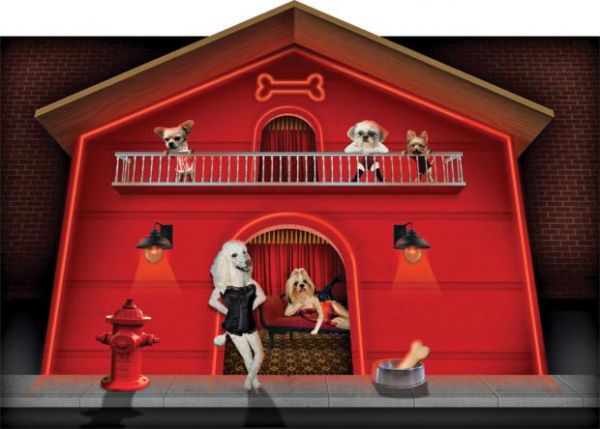

10. A Bordello of Barks

Joey

Skaggs is a professional prankster who plays the media like his

instrument. He’s made waves posing as an outraged gypsy hell-bent on

renaming the gypsy moth. He launched Walk Right!—a fictional group

dedicated to enforcing proper walking etiquette through militant

tactics. But perhaps the best illustration of his life’s work is the

brothel for dogs that he opened in 1976. The prank started when Skaggs

ran an ad in The Village Voice offering dog owners a chance to

buy their pets a night with alluring companions, including Fifi, the

French poodle. To Skaggs’s surprise, he began getting calls from people

wanting to drop $50 for his service.

Joey

Skaggs is a professional prankster who plays the media like his

instrument. He’s made waves posing as an outraged gypsy hell-bent on

renaming the gypsy moth. He launched Walk Right!—a fictional group

dedicated to enforcing proper walking etiquette through militant

tactics. But perhaps the best illustration of his life’s work is the

brothel for dogs that he opened in 1976. The prank started when Skaggs

ran an ad in The Village Voice offering dog owners a chance to

buy their pets a night with alluring companions, including Fifi, the

French poodle. To Skaggs’s surprise, he began getting calls from people

wanting to drop $50 for his service.It didn’t take much for the media to bite, and when reporters showed up with questions, Skaggs reeled them in by staging a night at his “cathouse for dogs.” The stunt worked; TV stations issued breathless reports of the wanton acts of canine carnality. The ASPCA launched an investigation, a veterinarian publicly condemned the brothel, and the New York Health Department raised concerns about Skaggs’s licensing.

Skaggs eventually admitted the whole thing was a goof, but not everyone believed him. To this day, a television producer for WABC New York argues that the brothel was real and that Skaggs’s hoax claims are just a clumsy attempt to cover his trail. Of course, WABC has good reason to insist that Skaggs was running a genuine poodle prostitution ring: The station won an Emmy for its coverage of the story.

11. MIT Blows Up Harvard!

MIT students derive great pleasure from tormenting their rivals at Harvard. Our favorite prank of theirs occurred during the 1982 Harvard-Yale football game when a weather balloon emblazoned with the letters “MIT” began emerging from the ground near the 50-yard line. In the preceding days, a group of MIT students had snuck into Harvard Stadium and wired a vacuum motor to blow air into the balloon until it exploded, proving once again why you don’t mess with engineers.12. Greasing the Wheels

Back in the late 19th century, college teams took trains to get to road games, and Auburn took full advantage of the situation. For a few seasons, students ran grease along the train tracks before Georgia Tech games, making it impossible for the train to stop anywhere near the station. Year after year, the poor football team ended up lugging its gear a number of miles back to the station, giving the players more of a warm-up than they bargained for and tilting the games in Auburn’s favor.13. Card Talk

14. The Elusive Northwest Tree-Dwelling Octopus

According

to the species’s official website, the Pacific Northwest tree octopus

is native to the rainforests of Washington State’s Olympic Peninsula.

It spends most of its time frolicking on treetops and snacking on frogs

and rodents. But today, the arboreal cephalopod faces extinction

thanks to rampant predation by the Sasquatch.

According

to the species’s official website, the Pacific Northwest tree octopus

is native to the rainforests of Washington State’s Olympic Peninsula.

It spends most of its time frolicking on treetops and snacking on frogs

and rodents. But today, the arboreal cephalopod faces extinction

thanks to rampant predation by the Sasquatch.That last detail gives away the joke to most people. But not everyone is so discerning. The octopus’s meticulous creator—known online as Lyle Zapato—doesn’t just throw hoaxes onto the web—he brilliantly links back to dozens of external sites listing everything from short stories about tree octopuses to videos of a baby tree octopus hatching to recipes for cooking them. And he throws in just enough legitimate links to throw readers off his scent. In fact, every statement is laboriously cross-referenced; most Wikipedia pages would be lucky to have this many sources.

Taken together, Zapato’s labyrinth of sites can trick even savvy web surfers into thinking this tree-dwelling octopus exists. A 2006 study by the University of Connecticut showed that 25 out of 25 web-proficient middle-schoolers fell for the hoax. Even when researchers told them that tree octopuses don’t exist, the students couldn’t identify the clues on the site to prove that it wasn’t factual. The plight of the Pacific Northwest tree octopus is just one of Zapato’s many causes; he maintains an elaborate site dedicated to promoting the Bureau of Sasquatch Affairs and one that alleges that the nation of Belgium doesn’t exist (the deceptive branding of Belgian waffles fits into his conspiracy theory). Of course, whether you look at it as art or entertainment, Zapato’s handiwork is a reminder not to believe everything you read on the Internet.

No comments:

Post a Comment