In the village of Tappan in Rockland County, New York, there is a circular plot of ground dedicated to the memory of Major John André, a British Army officer whom General George Washington ordered hanged for spying.

Isn’t that rather odd? Although Americans might be polite to the memories of their British oppressors, it seems unusual to erect a monument to an enemy. We have to back up a bit to understand why Americans would build and maintain this monument.

John André (1751-1780) of London purchased a lieutenancy in the British Army in 1771. In 1775, he was captured by American rebels attacking Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu, Quebec. After being exchanged, he saw action at the Battle of Brandywine. During the British occupation of Philadelphia in 1778 by General Howe, André worked as a stage actor and director. He organized the famous (or infamous) Mischianza banquet—a grand spectacle of performances and feasts to bid farewell to General Howe upon his recall to Britain. André not only ran this fête, but contributed to it by composing poetry in Howe’s honor and participating in a joust.

André was an enormously popular officer—especially with the generals. General Clinton appointed him to the position of senior intelligence officer. This work brought him into contact with the American General Benedict Arnold, who was then discreetly seeking a better deal from the British.

The Capture of Major André by Asher Brown Duran

Major

André convinced Arnold to switch sides and hand over the American fort

at West Point, New York in the process. At the end of a secret meeting,

Arnold persuaded André to dispose of his British uniform and ride back

to British lines in civilian clothes. André took the advice. While

traveling back to base, American militiamen detained and searched André.

They caught him out of uniform and carrying plans for West Point in one

of his boots.As a consequence, the Americans considered him to be a spy, not a prisoner of war.

General Washington convened in Tappan a court martial with a board of 14 officers to judge André. While in captivity, André charmed his captors. Nonetheless, the tribunal found him guilty of espionage and sentenced him to death.

The British were keen to rescue one of their favorite and best-loved officers. Washington, eager to get his hands on Benedict Arnold, offered to exchange André for Arnold. Arnold, for his part, threatened to execute 40 American prisoners of war from South Carolina if André was killed.

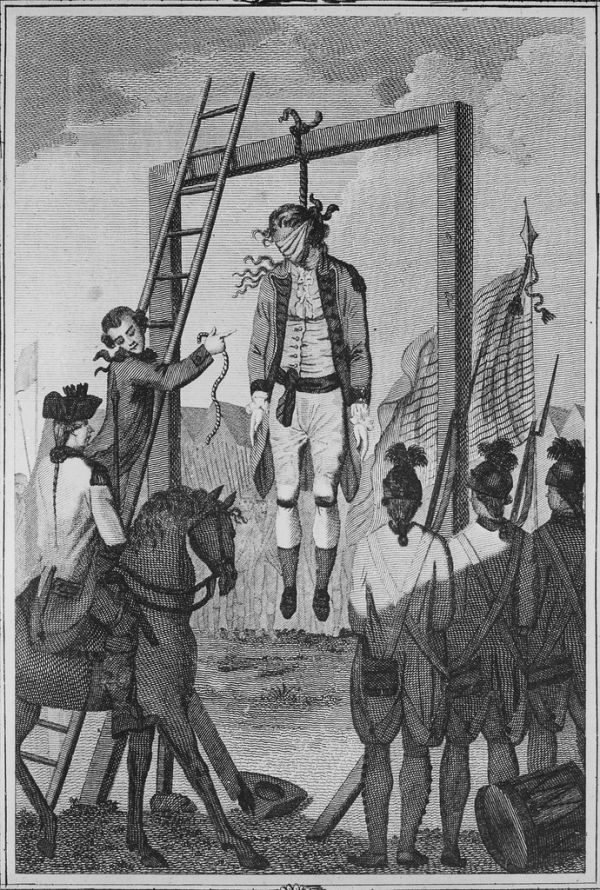

Nothing came of the negotiations. André would die. He requested that his execution come from a firing squad, as befitting a soldier. Washington refused. André was a spy and would hang like one. On October 2, 1780, André’s life ended in a noose in Tappan.

Engraving by John Goldar

Popular

legend holds that throughout his captivity, André deeply impressed his

American captors with his dignity and gentlemanly manners. He faced the

gallows bravely and died well. In his poem “On Sir Henry Clinton’s Recall,” the American nationalist Philip Freneau blamed General Clinton for André’s death:So off you sent Andrè (not guided by Pallas)The handsome and dashing André was a popular British hero of the war. In 1821, at his own expense, King George IV re-interred André in an ornate marble sarcophagus in Westminster Abbey.

Who soon purchas'd Arnold, and with him the gallows;

Your loss I conceive than your gain was far greater,

You lost a good fellow, and got a vile traitor.

The original grave-site also bears a memorial to Major John André. Cyrus W. Field, an American businessman, commissioned it in 1879. There a stone tablet marks the spot where fell an enemy officer whom General Washington called “more unfortunate than criminal.”

No comments:

Post a Comment