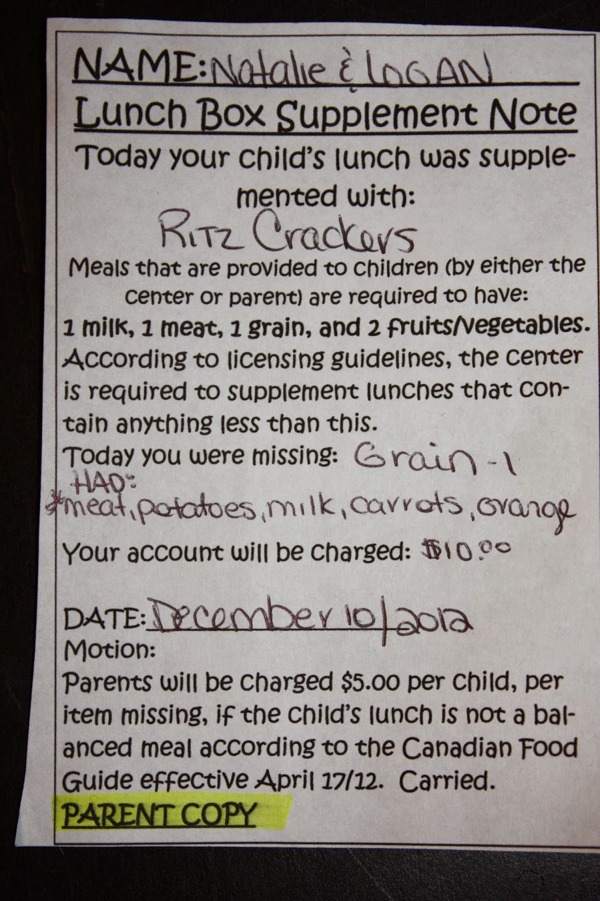

By Nadia Drake

The

brown recluse spider’s reputation vastly exceeds its reality. Note the

three pairs of eyes: That’s the best way to identify these guys.

It’s hard to think of a critter that inspires as much hyperbolic

hysteria as the brown recluse spider. They’re pretty much universally

hated. If you believe the tales, these small arachnids are biting people

all day, every day, producing massive, stinking flesh-craters that

require months of intensive care and perhaps a prosthetic appendage.

Sometimes, it seems these spiders have nothing better to do than hunker

down in dark corners throughout North America, waiting for tender human

skin to present itself.

Though there are strands of truth in the hype, on the whole, it’s bunk.

Verified bite of L. reclusa. William V. Stoecker/Swanson & Vetter, New England Journal of Medicine, 2005

It is true that some of the spider’s bites lead to necrotic skin

lesions, but around 10 percent of them. The others (like the one at

right), aren’t that bad. The brown recluse (

Loxosceles reclusa)

only lives in a few states – basically, the warmer ones between the

Rockies and the Appalachians. And they don’t really want to bite you.

It’s actually not that easy for them.

The brown recluse reality is obscured by a number of factors, not the

least of which involves gnarly internet photos. First, spiders in

general are easy to fear, and misinformation about this species in

particular abounds. Second, bite wound statistics are clouded by

misreporting. Third, many other conditions can be misdiagnosed as brown

recluse bites (like MRSA and fungal infections). Lastly, many other

spiders (and insects) are mistaken for brown recluses.

“There is a really strong emotional and psychological aspect to the brown recluse,” said arachnologist

Rick Vetter, now retired from the University of California, Riverside.

Inspired by the comments left on a story we did about the silk of a closely related recluse spider,

the South American brown recluse, we decided to take a close look at

our own continent’s most despised brown spider and the myths surrounding

it.

First, a truth: Brown recluse bites can be bad. “They are a potentially dangerous spider,” said Vetter, who has spent decades

studying the brown spiders. “They’re not harmless,” he says. “But the reputation they have garnered in this country is just amazing.”

Cases of Mistaken Identity

Much of Vetter’s work has involved verifying the identity of spiders

purported to be brown recluses. In 2005, Vetter published the results of

a nationwide appeal for

spider specimens suspected to be L. reclusa:

Please send me the spiders you think are brown recluses, and tell me

where you’re from. He received 1,773 specimens, from 49 states. Less

than 20 percent — 324 — were brown recluses. All but four of those came

from states with endemic brown recluse populations.

“An initial goal of this study was to determine the spider

characteristics that people were misconstruing as that of a brown

recluse,” he wrote. “It became evident early in the study that all that

was required was some brown [body] coloration and eight legs.”

‘People jump at the chance to hate spiders. It’s easier to vilify them than to adore their biology and natural history.’

Along the way, Vetter realized that authorities — such as poison

control centers and physicians — aren’t much better at identifying the

brown recluse. Even trained entomologists can get it wrong.

In 2009, Vetter

took a close look at 38 arachnids

incorrectly identified as recluses by 35 different authorities such as

“physicians, entomologists, pest control operators – people you’d think

would have reliable opinions,” Vetter said. Misidentifications included a

solifuge (which isn’t even a spider), a grass spider pulled from a patient’s ear, and a desert grass spider that had bitten a young boy.

Part of the problem is that the brown recluse is small and brown and

about the size of a quarter — like many other arachnids and insects. The

best way to identify a brown recluse is to count its eyes: They’re

among a few species of North American spiders that have six eyes instead

of eight, arranged in three pairs of two.

But your typical spider-squisher isn’t going to get in a spider’s

face with a magnifying glass and count its eyes. Some people may try to

find the marking most commonly described as identifying a brown recluse:

a violin shape on the spider’s head, oriented with the violin’s neck

pointing toward the spider’s butt.

However, people are incredibly good at “seeing” violin markings on

every portion of a spider’s body, Vetter says, which means this marking

isn’t an especially helpful diagnostic.

A Disconnect Between Bite Reports and Sightings

Brown recluse spiders (L. reclusa) live in the red blob. Not noted on this diagram are several small populations of L. laeta, the Chilean recluse whose silk we reported on earlier, that live near Los Angeles. Small, brown spiders run around pretty much everywhere on Earth. But

the brown recluse only lives in a few states between the Rocky Mountains

and the Appalachians.

“Arkansas and Missouri are the two states where they’re very, very

dense,” Vetter said. Kansas, Oklahoma, the western portions of Tennessee

and Kentucky, the southern parts of Indiana and Illinois, and the

northeastern parts of Texas round out the recluse’s range.

Though the spiders can travel around – maybe in luggage, or freight –

it’s uncommon to find a brown recluse outside its native range. Still,

reports of brown recluse bites from states outside the recluse range

abound. For example, Vetter and his colleagues

studied six years of brown recluse bite records,

derived from three poison control centers in Florida. A total of 844

brown recluse bites were reported. But in 100 years of arachnological

data, only 70 recluse spiders (not all of them brown recluses) have been

found in the entire state.

Vetter took a similar look at Georgia, a state on the margins of the recluse’s range. They’d asked that

any and all suspected recluse specimens be submitted for identification.

More than 1,000 spiders came in, but only 19 were brown recluses. In

the state’s arachnological history — derived from searching through

museum collections, historical records, websites, and storage buildings

in parks — there were only about 100 verified brown recluse sightings,

mostly in the northwest portion of the state. But a five-year dataset

from the Georgia Poison Center contained 963 reports of brown recluse

spider bites.

Similar patterns exist in northwest states – Washington, Oregon, and

Idaho – that are far outside the spider’s range, and other states on the

spiders’ margins, like Indiana.

Cases of Mistaken Diagnosis

Vetter and other experts suspect that the brown recluse bite

diagnosis is a popular catch-all for situations where the cause of a

skin lesion can’t be easily identified. True, there are

many things that can cause a nasty-looking flesh wound

— but the brown recluse diagnosis carries an unlikely charisma. “If you

get a bacterial infection, do you tell anyone about it? Of course not,”

Vetter said. “But if you think you got a brown recluse bite, you tell

everybody! You put it in your Christmas letter.”

This is NOT a brown recluse bite. It’s anthrax, misdiagnosed as a brown recluse bite. From Swanson and Vetter, New England Journal of Medicine, 2005

Over the years, Vetter and his colleagues have compiled

a list of about 40 things that can masquerade as recluse bites:

bacterial infections, viral infections and fungal infections; poison

oak and poison ivy; thermal burns, chemical burns; bad reactions to

blood thinners; herpes.

“People want to believe [the culprit] is a spider species,” said

entomologist Chris Buddle of McGill University, noting that it’s easier to blame a spider than something less familiar, like drug-resistant bacteria.

Most physicians don’t have a lot of experience discriminating between a recluse bite and something like necrotizing

Staphylococcus.

And even if a patient brings in a spider for identification, it’s

unlikely the ER doctor has been trained to ID a brown recluse.

There are some ways in which brown recluse bites are different from

many other wounds, however. A raised, reddish and wet wound is likely

not a recluse bite, Vetter says. Recluse venom destroys small blood

vessels and causes them to constrict, turning the area around the bite

white, or purple, or blue. Fluids can’t flow to the area, and it sinks a

little, and dries out.

In reality, just 10 percent of recluse bites require medical

attention. The rest look like little pimples or mosquito bites or

something else that doesn’t merit a trip to the emergency room, and they

heal by themselves. But the reality about bite statistics doesn’t seem

to matter. Even when faced with numbers and geographic distribution

maps, people still cling tightly to their beliefs about the recluse and

its arachnid malfeasance.

The Persistence of Myth

It is true that brown recluses like hiding in dark corners. They’re

nocturnal and shy away from daylight and, sometimes, the outdoors. Hence

the name. But they are not waiting in these dark corners to bite

you. It’s possible to live with the spiders and not get bitten. Take the

rather extreme example of a Kansas family that lived for six years in

a

house infested by 2,055 brown recluse spiders. Total bites: Zero.

In fact, the spiders’ fangs are too short and small to bite through

pajamas or socks, and really only sturdy enough to puncture thin

skin. Most bites occur when people roll over on the spiders in the

night, or try to wear a shoe the spider has moved into. “Biting is a

response to being crushed, but they’d much rather try and get away,”

Vetter said.

‘If you get a bacterial infection, do you

tell anyone about it? Of course not. But if you think you got a brown

recluse bite, you tell everybody’

But the idea that something hazardous lurks in the dark, out of sight

behind a toilet or inside a shoe, is a potent source of fear. The idea

lodges in the psyche and is difficult to shake loose – especially when

fed by popular media and peers. “The press has, by and large, painted

spiders in a negative light,” Buddle said. “People jump at the chance to

hate spiders. It’s easier to vilify them than to adore their biology

and natural history.”

Things that are potentially harmful, move erratically, unpredictably,

and sometimes quickly, are easy to fear. Spiders fall into this

category, says psychologist

Helena Purkis,

who has studied arachnophobia and fear of snakes at the University of

Queensland, Australia. And then, when people fear something, they expect

it to be associated with bad things.

“The truth is, bad things happen to us all the time, and it’s completely random,” said entomologist Gwen Pearson, author of the WIRED Science Blog, Charismatic Minifauna.

But being able to blame a nasty skin lesion on a spider is more

satisfying than acknowledging that a necrotic crater has emerged on your

arm for no identifiable reason, she says.

Purkis described an experiment in which shocks were randomly paired

with either pictures of flowers, or pictures of spiders. “People report

that spiders, but not the flowers, were predictive of shocks – even when

the presentations were completely random,” she said.

Searching for patterns in the noise is one of the ways human brains

handle the overwhelming amount of stimuli in the world — but it also

leads to misperceptions. Here, our fallibility is in our tendency to

filter new information and remember facts more easily if they are

consistent with our beliefs, Purkis says. This means that you could hear

one bad story about a brown recluse bite and 10 stories about how the

spiders aren’t so bad, and guess which one will stick?

I

suspect that most Americans will be familiar with both terms, thanks to

the prevalence of British television in the United States (thank you, Doctor Who and Downton Abbey).

I

suspect that most Americans will be familiar with both terms, thanks to

the prevalence of British television in the United States (thank you, Doctor Who and Downton Abbey).

The human mind is amazingly resilient, which becomes evident in so many different ways. One is

The human mind is amazingly resilient, which becomes evident in so many different ways. One is