1. Herbert Hoover (President #31, 1929–1933)

Although Herbert Hoover won the 1928 presidential election with

almost 60 percent of the vote, today he’s basically remembered as a dam.

Actually, many Americans probably think he was an FBI director or the

guy who invented a vacuum. But Hoover was, in fact, a U.S. president —

and an interesting one to boot. Orphaned at age 9, he worked and scraped

his way into the newly minted Stanford University to study mining

engineering. There, he married Lou Henry, the only female geology

student at the school, and the pair traveled the world evaluating mining

sites and learning languages. (In the White House, they often spoke in

Mandarin when they didn’t want staff eavesdropping.) Hoover’s successful

coordination of the U.S. Food Administration during WWI paved his way

to the Oval Office. Although massively popular early in his term, a

little thing called the Great Depression came along and seriously soured

his approval rating. Herbert battled bravely against the dusty tide of

poverty, but his programs were largely ineffective. Sorry, Herbert.

Great dam, though. Great dam.

Although Herbert Hoover won the 1928 presidential election with

almost 60 percent of the vote, today he’s basically remembered as a dam.

Actually, many Americans probably think he was an FBI director or the

guy who invented a vacuum. But Hoover was, in fact, a U.S. president —

and an interesting one to boot. Orphaned at age 9, he worked and scraped

his way into the newly minted Stanford University to study mining

engineering. There, he married Lou Henry, the only female geology

student at the school, and the pair traveled the world evaluating mining

sites and learning languages. (In the White House, they often spoke in

Mandarin when they didn’t want staff eavesdropping.) Hoover’s successful

coordination of the U.S. Food Administration during WWI paved his way

to the Oval Office. Although massively popular early in his term, a

little thing called the Great Depression came along and seriously soured

his approval rating. Herbert battled bravely against the dusty tide of

poverty, but his programs were largely ineffective. Sorry, Herbert.

Great dam, though. Great dam.2. Martin Van Buren (President #8, 1837–1841)

Despite earning catchy nicknames such as “The Little Magician” and

“The Red Fox of Kinderhook” on the political battlefield, M.V.B. is far

from the MVP of the American presidency. One title he can claim, though,

is that of the first president not of British descent. Van Buren was

the son of a Dutch tavern owner and gained his taste for politics

listening to debates in the rowdy rooms of the family saloon. A

self-taught lawyer, the politically adept Van Buren quickly rose up the

governmental ranks, landing a spot as President Andrew Jackson’s

secretary of state in 1828. By keeping clear of the Cabinet infighting

that marred Jackson’s first term, Van Buren replaced John Calhoun as

Jackson’s vice president in the second term. In 1836, he won the

presidency, but soon fizzled out in a daze of leadership defeats and

ineffective policies. Don’t look for him on the penny any time soon.

Despite earning catchy nicknames such as “The Little Magician” and

“The Red Fox of Kinderhook” on the political battlefield, M.V.B. is far

from the MVP of the American presidency. One title he can claim, though,

is that of the first president not of British descent. Van Buren was

the son of a Dutch tavern owner and gained his taste for politics

listening to debates in the rowdy rooms of the family saloon. A

self-taught lawyer, the politically adept Van Buren quickly rose up the

governmental ranks, landing a spot as President Andrew Jackson’s

secretary of state in 1828. By keeping clear of the Cabinet infighting

that marred Jackson’s first term, Van Buren replaced John Calhoun as

Jackson’s vice president in the second term. In 1836, he won the

presidency, but soon fizzled out in a daze of leadership defeats and

ineffective policies. Don’t look for him on the penny any time soon.3. Warren Harding (President #29, 1921–1923)

Warren G. Harding is generally regarded as the worst president ever.

He was disappointing from the get-go, as the very basis of his campaign

was boring. Harding ran on the promise of a “return to normalcy,” which

he (somehow) felt people craved following Woodrow Wilson’s bold and

visionary term. To make things worse, Harding ran the White House like a

kind of boys’ club, where he and some friends known as the “Ohio Gang”

enjoyed drinking, playing golf, and cheating on their wives. (Harding is

widely rumored to have paid a gambling debt with antique White House

china.) After admitting to friends that he felt overmatched by the job

of president, Harding gave his Cabinet free reign and treated the

presidency as more of a ceremonial post. Just as the friends he’d

appointed were being nailed for corruption one after another, Harding

contracted what doctors assumed was ptomaine poisoning and died of a

related heart attack. No autopsy was performed, but rumors abounded that

his wife poisoned him to protect what legacy he had left.

Warren G. Harding is generally regarded as the worst president ever.

He was disappointing from the get-go, as the very basis of his campaign

was boring. Harding ran on the promise of a “return to normalcy,” which

he (somehow) felt people craved following Woodrow Wilson’s bold and

visionary term. To make things worse, Harding ran the White House like a

kind of boys’ club, where he and some friends known as the “Ohio Gang”

enjoyed drinking, playing golf, and cheating on their wives. (Harding is

widely rumored to have paid a gambling debt with antique White House

china.) After admitting to friends that he felt overmatched by the job

of president, Harding gave his Cabinet free reign and treated the

presidency as more of a ceremonial post. Just as the friends he’d

appointed were being nailed for corruption one after another, Harding

contracted what doctors assumed was ptomaine poisoning and died of a

related heart attack. No autopsy was performed, but rumors abounded that

his wife poisoned him to protect what legacy he had left.4. James Monroe (Presidet #5, 1817-1825)

Monroe is proof that being a good president doesn’t make you memorable.

It’s a shame though, because the guy led a pretty memorable life. While

still a teenager, he inherited his family’s plantation and ran it before

heading off to college. He later dropped out of school to fight in the

American Revolution. After gaining distinction as a leader and a

patriot, Monroe was named the U.S. minister to France in 1794, and five

years later, he was elected governor of Virginia. When Monroe took over

the presidency, the country was on a high from a booming economy, so his

political obstacles were easily vaulted. In fact, when it came time for

re-election in 1820, everyone was so fat and happy they just said, “Eh,

keep it up,” and let him run (mostly) unopposed. His presidency has

been called the “Era of Good Feelings,” and while J.M. doesn’t get much

airtime nowadays, he’s got no reason to hang his head.

Monroe is proof that being a good president doesn’t make you memorable.

It’s a shame though, because the guy led a pretty memorable life. While

still a teenager, he inherited his family’s plantation and ran it before

heading off to college. He later dropped out of school to fight in the

American Revolution. After gaining distinction as a leader and a

patriot, Monroe was named the U.S. minister to France in 1794, and five

years later, he was elected governor of Virginia. When Monroe took over

the presidency, the country was on a high from a booming economy, so his

political obstacles were easily vaulted. In fact, when it came time for

re-election in 1820, everyone was so fat and happy they just said, “Eh,

keep it up,” and let him run (mostly) unopposed. His presidency has

been called the “Era of Good Feelings,” and while J.M. doesn’t get much

airtime nowadays, he’s got no reason to hang his head.5. Chester Arthur (President #21, 1881–1885)

Most people don’t know ol’ Chesty for anything other than his mammoth

moustache. But he should be remembered as a guy who rose to the

occasion. As a young man, Arthur worked on civil rights cases in New

York before succumbing to the corrupt New York political machine of

Roscoe “Boss” Conkling. (How anyone could fail to detect corruption in

someone named Roscoe “Boss” Conkling is beyond us.) In 1881, Arthur

became vice president under James Garfield, but soon butted heads with

the president over an appointment that sapped Conkling’s power. In fact,

Arthur and Garfield were hardly communicating when, a few months later,

Garfield was assassinated, and Arthur suddenly became the big cheese.

Instead of behaving like a pawn as everyone expected, Arthur became a

man of the people, taking steps to cut back on cronyism and rebuffing

pressures from big business. And what do you call him? The president

with the big moustache. Nice going!

Most people don’t know ol’ Chesty for anything other than his mammoth

moustache. But he should be remembered as a guy who rose to the

occasion. As a young man, Arthur worked on civil rights cases in New

York before succumbing to the corrupt New York political machine of

Roscoe “Boss” Conkling. (How anyone could fail to detect corruption in

someone named Roscoe “Boss” Conkling is beyond us.) In 1881, Arthur

became vice president under James Garfield, but soon butted heads with

the president over an appointment that sapped Conkling’s power. In fact,

Arthur and Garfield were hardly communicating when, a few months later,

Garfield was assassinated, and Arthur suddenly became the big cheese.

Instead of behaving like a pawn as everyone expected, Arthur became a

man of the people, taking steps to cut back on cronyism and rebuffing

pressures from big business. And what do you call him? The president

with the big moustache. Nice going!6. Millard Fillmore (President #13, 1850–1853)

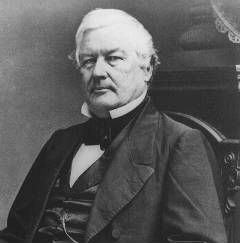

Today, Millard Fillmore’s name is synonymous with overlooked. Need

proof? In February 2006, a group called the Friends of Millard Fillmore

hosted the 38th annual FOMF Trivia Hunt, a contest celebrating obscure

knowledge. Fillmore was born in 1800 to a destitute family, but thanks

to a merciless work ethic, he taught himself to read and eventually

became a lawyer. That quickly segued into politics, and in 1848, the

Whigs ran Fillmore for VP alongside Zachary Taylor. The pair won the

election, but remained divided by their views on slavery (Taylor being a

southern slave owner, and Fillmore, well, not). When Taylor died,

Fillmore tried to appease the North and South by supporting the

Compromise of 1850. Unfortunately, the move alienated the North and

created a fair share of enemies on both sides. Thus tainted, he lost

several bids for re-election and died of a stroke in 1874.

Today, Millard Fillmore’s name is synonymous with overlooked. Need

proof? In February 2006, a group called the Friends of Millard Fillmore

hosted the 38th annual FOMF Trivia Hunt, a contest celebrating obscure

knowledge. Fillmore was born in 1800 to a destitute family, but thanks

to a merciless work ethic, he taught himself to read and eventually

became a lawyer. That quickly segued into politics, and in 1848, the

Whigs ran Fillmore for VP alongside Zachary Taylor. The pair won the

election, but remained divided by their views on slavery (Taylor being a

southern slave owner, and Fillmore, well, not). When Taylor died,

Fillmore tried to appease the North and South by supporting the

Compromise of 1850. Unfortunately, the move alienated the North and

created a fair share of enemies on both sides. Thus tainted, he lost

several bids for re-election and died of a stroke in 1874.7. Franklin Pierce (President #14, 1853-1857)

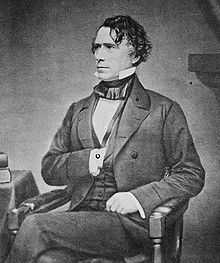

The son of a two-term New Hampshire governor, Pierce rode the

coattails of nepotism into the U.S. House and Senate by age 30. In 1852,

he came out of nowhere to win the presidency. He beat out seemingly

more dedicated candidates with a platform essentially based on trying to

avoid the hot-button issue of slavery. But his presidency didn’t get

off to a good start. Two months before Pierce took office, his

11-year-old son was killed in a train wreck. Hampered by heartbreak,

Pierce tried not to rock the boat of peace between the North and South,

but that plan didn’t exactly pan out. By signing the Kansas-Nebraska Act

in 1854, he inadvertently launched a frenzy of shooting matches in

Kansas and re-awakened the conflict surrounding slavery. The Democrats

reeling, Pierce was abandoned and denied the chance to run for a second

term.

The son of a two-term New Hampshire governor, Pierce rode the

coattails of nepotism into the U.S. House and Senate by age 30. In 1852,

he came out of nowhere to win the presidency. He beat out seemingly

more dedicated candidates with a platform essentially based on trying to

avoid the hot-button issue of slavery. But his presidency didn’t get

off to a good start. Two months before Pierce took office, his

11-year-old son was killed in a train wreck. Hampered by heartbreak,

Pierce tried not to rock the boat of peace between the North and South,

but that plan didn’t exactly pan out. By signing the Kansas-Nebraska Act

in 1854, he inadvertently launched a frenzy of shooting matches in

Kansas and re-awakened the conflict surrounding slavery. The Democrats

reeling, Pierce was abandoned and denied the chance to run for a second

term.8. Rutherford B. Hayes (President #19, 1877–1881)

Rutherford B. Hayes is slightly more memorable due to the catchiness

of his name, but he’s still more than obscure enough to make our list.

Raised by a single mother, Hayes worked his way up in the world from

next to nothing, studying at Harvard and practicing law in Cincinnati.

When the Civil War erupted, Hayes was 39 and a father of three.

Nonetheless, he volunteered to fight and quickly distinguished himself

as a valuable leader. After parlaying this fame into a Senate seat and

then the governorship of Ohio, he received the Republican presidential

nomination in 1876. Until the chad-alicious scandal of 2000, this was

perhaps America’s most contested election –ending with a special

Congressional committee declaring Hayes the winner over Samuel J. Tilden

by one electoral vote. Once he took office, Hayes got right to work

healing a nation still battered by the Civil War. He later claimed to

have inherited the country “divided and distracted” and left it “united,

harmonious and prosperous.” Unfortunately for ol’ Rutherford, harmony

and prosperity alone won’t get your mug on Mount Rushmore.

Rutherford B. Hayes is slightly more memorable due to the catchiness

of his name, but he’s still more than obscure enough to make our list.

Raised by a single mother, Hayes worked his way up in the world from

next to nothing, studying at Harvard and practicing law in Cincinnati.

When the Civil War erupted, Hayes was 39 and a father of three.

Nonetheless, he volunteered to fight and quickly distinguished himself

as a valuable leader. After parlaying this fame into a Senate seat and

then the governorship of Ohio, he received the Republican presidential

nomination in 1876. Until the chad-alicious scandal of 2000, this was

perhaps America’s most contested election –ending with a special

Congressional committee declaring Hayes the winner over Samuel J. Tilden

by one electoral vote. Once he took office, Hayes got right to work

healing a nation still battered by the Civil War. He later claimed to

have inherited the country “divided and distracted” and left it “united,

harmonious and prosperous.” Unfortunately for ol’ Rutherford, harmony

and prosperity alone won’t get your mug on Mount Rushmore. 9. John Tyler (President #10, 1841–1845)

9. John Tyler (President #10, 1841–1845)John Tyler was up against it from the start. For one thing, he only got to be president because he was the VP under William Henry Harrison, who died of pneumonia following his inauguration speech. Let’s put it this way: When your nicknames include “His Accidency,” you’re not destined to make a splash. After Harrison’s unscheduled departure, Tyler’s orchestration of an orderly transfer of power was his only recognized political success. Tyler didn’t want to alienate Harrison’s supporters, so he retained the departed president’s Cabinet. Unfortunately, they had little respect for their new leader. When he once vetoed a bill they favored, all but one of them resigned. That’s pretty much how the presidency went for Tyler. In fact, his own Whig party tried to have him impeached. Tyler gamely ran for re-election in 1844, but was persuaded to withdraw. Broke, Tyler returned to his Virginia plantation and spent a lot of time supporting the secession of the South. (That didn’t work out so well either.)

10. Zachary Taylor (President #12, 1849-1850)

Despite his privileged upbringing, ownership of slaves, and

reputation as an “Indian fighter,” Zachary Taylor was the most popular

man in America when he won the election in 1848. Like many members of

our list, Taylor spent much of his presidency wrestling with the

question of slavery. Unfortunately, this left little time for him to

wrestle with the question of how not to contact cholera, and he

died of the disease in 1850. Millard Fillmore took office next, almost

immediately signing the Compromise of 1850 and wiping out what little

progress Taylor had made. Welcome to the annals of anonymity, Zach.

Despite his privileged upbringing, ownership of slaves, and

reputation as an “Indian fighter,” Zachary Taylor was the most popular

man in America when he won the election in 1848. Like many members of

our list, Taylor spent much of his presidency wrestling with the

question of slavery. Unfortunately, this left little time for him to

wrestle with the question of how not to contact cholera, and he

died of the disease in 1850. Millard Fillmore took office next, almost

immediately signing the Compromise of 1850 and wiping out what little

progress Taylor had made. Welcome to the annals of anonymity, Zach.

No comments:

Post a Comment