Judging

from what we’ve been told in history books, when the Wright Brothers

invented powered flight, they were rewarded with parades, medals, and

headlines. But that’s a lie. The truth is, the U.S. government insisted

that one of the greatest technological achievements of all time simply

hadn’t happened. Here’s the true story.

CHANCE- THE UNINVITED GUEST

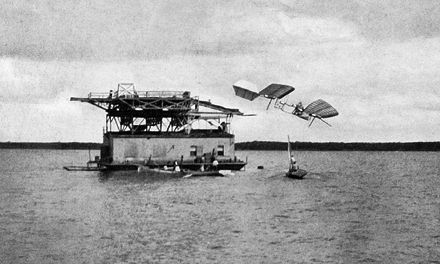

On

December 8, 1903, Samuel Langley, head of the Smithsonian Institution

and America’s foremost expert on flight, was ready to make his most

important attempt at manned flight. Since 1891 he’d been flying unmanned

models powered by internal combustion engines; the U.S. government

considered his experiments so promising that they’ve given him $50,000

to continue. Now he planned to fly his gasoline-powered, manned flight

off of a houseboat in the Potomac River. The press was on hand, waiting

expectantly.

But it didn’t happen. Unfortunately, the launching

device, which was supposed to hurl the plane into the air, snagged the

plane at the last second instead… and it went into the water “like a

handful of mortar.”

The

New York Times,

scornful of attempts at powered flight anyway, heaped abuse on Langley.

They editorialized: “The ridiculous fiasco… was not unexpected. The

flying machine might be evolved by the combined and continuous efforts

of mathematicians and mechanics in from one to ten million years.”

THE REAL THING

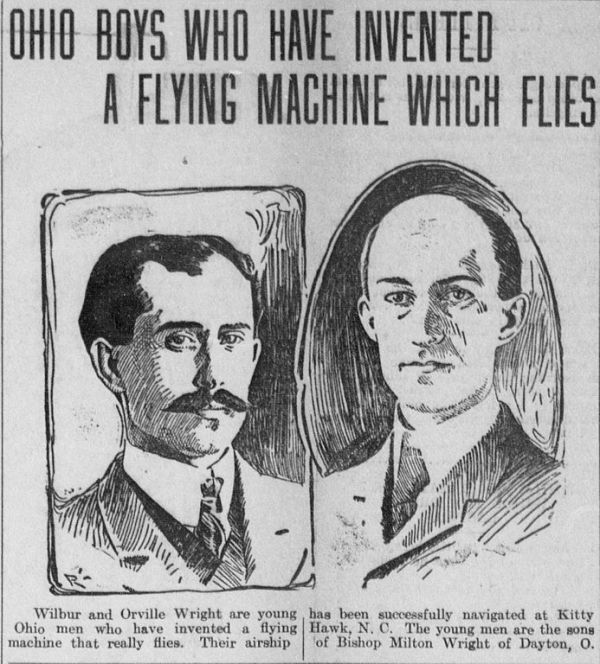

It

didn’t take that long. Only nine days later, on December 17, two

bicycle makers from Dayton, Ohio -Wilbur and Orville Wright- achieved

the goal of all the world’s would-be aviators: powered flight. It was a

revolutionary development in the history of humankind …but few people

even noticed. Only a few papers carried the Associated Press story of

the flight. Most editors considered the whole thing a scam. When the

Wrights set up the world’s first airstrip outside Dayton in 1904 and

flew daily all summer, only a few reporters came to see.

In fact, the first published eyewitness account of flight appears, amazingly enough, in a beekeeping journal called

Gleanings in Bee Culture.

And this almost a year after they started flying. The editor, A.I.

Root, saw the Wrights make aviation’s first turn on September 20, 1904

and wrote:

I have a

wonderful story to tell you, a story that in some respects outrivals

the Arabian Nights fables… It was my privilege, on the 20th day of

September, 1904 to see the first successful trip of an airship, without a

balloon to sustain it, that the world has ever made… These two brothers

have probably not even a faint glimpse of what their discovery is going

to bring to the children of men.

The scientific press was also slow to acknowledge the Wrights’ accomplishment. As Sherwood Hayes writes in

The First To Fly:

Scientific

American had been skeptical of reports about the Wright Brothers long

flights, its editorial board feeling that if the reports were true, then

certainly the enterprising American press would have given them great

attention. When the reports persisted, the magazine finally obtained

confirmation by letter from many reputable people who had witnessed the

actual flights. In its December 15 [1906] issue, the magazine stated its

complete acceptance of the Wrights.

MILITARY INTELLIGENCE

You’d

think the U.S. government would leap to purchase one of the most

revolutionary weapons ever. Not so. In 1904 after making flights of five

minutes, the Wrights wrote their Congressman, Robert Nevin, offering to

license their device to the government for military purposes. Their

letter said they’d made 105 flights up to 3 miles long at 35 mph. The

flying machine, they said, “lands without being wrecked” and “can be are

of great practical use in scouting and carrying messages in time of

war.” Interestingly enough, for many years the

only use the Wrights could imagine for their creation was war.)

The

War Department, under future president William Howard Taft, responded

that they weren’t interested. They’d gotten many requests for “financial

assistance in the development of designs for flying machines” and would

only consider a device that had been “brought to the stage of practical

operation without expense to the U.S. government.” But, they added, do

get in touch “as soon as it shall have been perfected.”

In

October 1905, the Wrights wrote that they’d built a better plane and

made flights up to 39 minutes and over 20 miles. The War Department

again declined in a letter with almost the same wording -a form letter!

Obviously, either no one was reading their letters, or no one understood

what they were saying.

Showing incredible patience, the

frustrated Wrights politely wrote back again. This time they said they’d

build a flying machine to

any specifications the government

would name. The War Department, still clinging to the obvious

impossibility of powered flight, wrote back saying it “does not care to

formulate any requirements for the performance of a flying machine

…until a machine is produced with by actual operation is shown to be

able to produce horizontal flight and to carry an operator” -even though

they had already produced it. They were so dejected that they didn’t

fly again for two and half years.

ACCEPTED AT LAST

In

1907 a young balloon racer named Frank Lahm got a job with the Army

Signal Corps office in Washington, DC. He knew all the early flight

pioneers and had heard from them about the miracle achieved by the

Wrights. That, finally, was the Wrights’ big break. Fred Howard writes

in

Wilbur and Orville:

Lahn wrote a letter to

the Board of Ordnance and Fortification (of the Army Signal Corps),

urging that the brothers’ latest proposal for the sale of a Flyer

receive favorable action. It would be unfortunate, he said, if the U.S.

should not be the first to take advantage of [the] unquestioned military

value of the Wright Flyer. Lahm’s letter had the desired effect…

Wilbur

decided a fair price for the Flyer would be $25,000. The Board only had

$10,000… When Wilbur went to Washington to attend a formal meeting of

the Board, his frankness of manner and self-confidence worked their

usual magic and the Board assured him the entire $25,000 would be

forthcoming by drawing on an emergency fund left over from the

Spanish-American War.

MORE BUREAUCRATIC INSANITY

Apparently

nothing much has changed: Even though the Wrights were the only ones in

the world making practical airplanes, the U.S. government still had to

put a letter out for bids. So on December 23, 1907, it issued an

“Advertisement and specifications for a Heavier-Than-Air Flying

Machine,” capable of carrying two men at 40 mph and staying up for at

least an hour, then landing without serious damage. Critics howled. The

American Magazine of Aquatics

wrote, “There is not a known flying machine in the world which could

fulfill those specifications.” Amazingly, the Signal Corps got 41 bids,

with price tags ranging from $850 to $1 million. One was from a federal

prisoner who would build a plane for his freedom. Another had plans

written on wrapping paper and a third bidder offered to build planes by

the pound.

The Wrights, of course, got the contract.

I SEE LONDON, I SEE FRANCE

Still,

it was the French and British who first acknowledged the Wright

Brothers’ feats publicly. Shortly after winning the government contract

(but before they’d proved themselves by building the U.S. a plane),

Wilbur went to France to demonstrate their machine. The French were avid

aviators, and welcomed him enthusiastically… at first. Then, as he

rebuilt his plane (it had been damaged in shipping), working long hours

and living simply in a nearby room, they became suspicious. Why wasn’t

he more flamboyant?

Why didn’t he attend the rounds of parties, like

other celebrated French air pioneers?

Eventually,

the French and British press decided he was a charlatan. But on August

8, 1907, they changed their minds. “To make a long story short,”

recalled an American named Ross Browne, who was there to see Wilbur’s

first European flight, “he got into the machine that afternoon, got into

the air and made a beautiful circular flight. You should have seen the

crowd there. They threw hats and everything.”

STILL DUMB

Finally,

four years after the first flight, the Wright Brothers were heroes. But

there was one final insult: The Smithsonian Institution insisted that

the first manned flight had been Langley’s slam dunk into the Potomac.

They didn’t want the Wright Flyer, so it sat in a shed in Dayton until

1928… when Orville finally gave it to the London Museum of Science. Only

in 1942 did the Smithsonian bow to common knowledge, reverse its

position, and humbly asked for the plane. The Smithsonian restored it

and dedicated it in 1948, on the 45th anniversary of flight.

In

1907 a young balloon racer named Frank Lahm got a job with the Army

Signal Corps office in Washington, DC. He knew all the early flight

pioneers and had heard from them about the miracle achieved by the

Wrights. That, finally, was the Wrights’ big break. Fred Howard writes

in Wilbur and Orville:

In

1907 a young balloon racer named Frank Lahm got a job with the Army

Signal Corps office in Washington, DC. He knew all the early flight

pioneers and had heard from them about the miracle achieved by the

Wrights. That, finally, was the Wrights’ big break. Fred Howard writes

in Wilbur and Orville:

No comments:

Post a Comment