On Valentine’s Day, 1981, eleven-year-old Todd Domboski was walking

through a field in Centralia, Pannsylvania, when a 150-foot-deep hole

suddenly opened beneath his feet. Noxious fumes crept out as the boy

fell in. He only survived by clinging to some newly exposed tree roots

until his cousin ran over and pulled him to safety. What was happening

here …and why?

COAL COUNTRY

Eastern Pennsylvania in anthracite coal country. Back at the turn of

the 20th century, miners were digging nearly 300 millions tons of coal

per year from the region, leaving behind a vast subterranean network of

abandoned mine shafts. In May 1962, while incinerating garbage in an old

strip mine pit outside of Centralia, one of the many exposed coal seams

ignited. The fire followed the seam down into the maze of abandoned

mines and began to spread. And it kept spreading -and burning- for

years.

Mine fires in coal country are actually not all that uncommon. There

are currently as many as 45 of them burning in Pennsylvania alone.

Unfortunately, there’s no good way to put them out. But that doesn’t

stop people from trying.

* The most effective method to extinguish such a fire s to strip mine

around the entire perimeter of the blaze. That’s an expensive -and in

populated areas, impractical- proposition. Essentially, it means digging

an enormous trench, deep enough to get underneath the fires, which are

often more than 500 feet below the ground.

* An easier (but not much easier) method is to bore holes down into

the old mine shafts, and then pour in tons of wet concrete to make

plugs. Then more holes are drilled and flame-supressing foam is pumped

into the areas between the plugs. It, too, is a very expensive project,

and it doesn’t always succeed.

The cheapest way to deal with a mine fire by far is to keep an eye on

it and hope it burns itself out. (One fire near Lehigh, Pennsylvania,

burned from 1850 until the 1930s.) After a 1969 effort to dig out the

Centralia fire proved both costly and unsuccessful, they admitted defeat

and let the fire take its course. By 1980, the size of the underground

blaze was estimated at 350 acres, and large clouds of noxious smoke were

billowing out of the ground all over town. The ground temperature under

a local gas station was recorded at nearly 1,000ºF. Residents of the

once-thriving mountain town began to wonder if Centralia was a safe

place to live.

When the boy fell in the hole and almost died, the fire beneath

Centralia became a national news story. The sinkhole -cause by an effect

known as subsidence, which occurs when mine shafts collapse,

possibly because the support beams are on fire- put the town’s 1,600

residents in a fix. Their homes were suddenly worthless. They couldn’t

sell them and move someplace safer -no one in their right mind would buy

them.

The townsfolk were given a choice: a $660-million digging project

that might not work, or let the government buy their homes. They voted

345 to 200 in favor of the buyout, and an exodus soon began. By 1991,

$42 million had been spent buying out more than 540 Centralia homes and

businesses.

GHOST TOWN

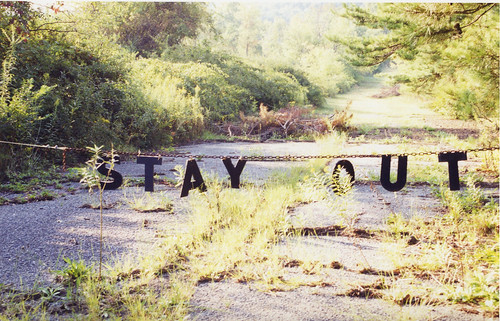

If you were to visit Centralia today, the first thing you’d notice is

that there are more streets than buildings. At first glance, it would

seem that someone decided to build a town, but only got as far as paving

the roads. If you looked a bit closer, however, you’d notice the

remnants of house foundations. Looking still closer, you’d see smoke

still seeping out of the ground.

As of 2005, twelve die-hard Centralians reportedly continue to live

in the smoldering ghost town. The number has dwindled since a decade

ago, when nearly fifty holdouts still called it home. Experts estimate

that it will take 250 years for the fire to burn itself out.

No comments:

Post a Comment