Any

group of malcontents can dress up like American Indians and toss tea

into a harbor to protest unfair taxation. But how many armies have

actually mobilized over food? Real food—as in, “Leggo my Eggo … or I’ll

send in the troops!” The answer? Not that many. Nevertheless, here are a

few of history’s greatest culinary-based conflicts.

Any

group of malcontents can dress up like American Indians and toss tea

into a harbor to protest unfair taxation. But how many armies have

actually mobilized over food? Real food—as in, “Leggo my Eggo … or I’ll

send in the troops!” The answer? Not that many. Nevertheless, here are a

few of history’s greatest culinary-based conflicts.First Course: The Bovine Brouhaha

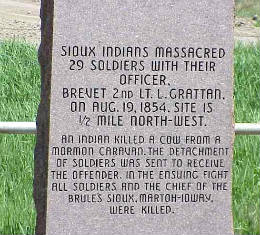

Grab a fork and a knife (and a rifle, if you’ve got one). First up on the menu is The Grattan Massacre, a bloody clash between American Indians and U.S. troops that played out in 1854 in the Nebraska Territory, just east of what is now Laramie, Wyoming.

If you thought Mrs. O’Leary’s cow was bad news, consider what the cow that wandered away from a Mormon pioneer train on the Oregon Trail started. The rabble-rousing bovine clomped its way into a camp inhabited by the Lakota Indians, one of seven tribes that made up the Great Sioux Nation. Not being ones to turn down a free lunch, the Lakota promptly killed the presumably abandoned cow and ate it.

That might not seem like a big deal, but in the mid-1800s, few peace pipes were being passed between American Indians and new settlers. So, when the cattle owner realized the fate his cow had met, he immediately went to tattle his tale at the Territory’s nearest outpost of officialdom, Fort Laramie. In response to the incident, U.S. officials dispatched an eager young second lieutenant and recent West Point graduate named John L. Grattan to bring the cow thieves to justice.

What happened next underscores the downside of history’s insistence on naming events only after they happen. Had John L. Grattan known he was riding off to The Grattan Massacre, it seems likely he might have conducted himself more civilly with the Sioux. Instead, Grattan’s approach would later prompt a fellow Fort Laramie officer to comment, “There is no doubt that Lt. Grattan left this post with a desire to have a fight with the Indians, and that he had determined to take the man at all hazards.”

Conquering Bear

When news of the event reached the U.S. War Department, officials sought swift revenge on the Sioux. A little more than a year after the Grattan Massacre, on September 3, 1855, General William S. Harney and roughly 600 soldiers caught up with the Lakota tribe. Harney ordered his men to open fire, and nearly 100 Lakota men, women, and children were shot dead in what became known as the Battle of Ash Hollow. (Apparently, 30 Army men being killed equals a massacre, while 100 Sioux being killed equals a battle. Ain’t history grand?)

Second Course: The Breadfruit Battle Royale

History often depicts the infamous mutiny on the Bounty as a power struggle between Captain William Bligh and his crew. But it wasn’t about that at all. It was about breadfruit.

On August 16, 1787, 33-year-old Lieutenant William Bligh was named commander of the Bounty. Two months later, the ship was commissioned to sail to Tahiti, pick up some breadfruit plants, and deliver them to the West Indies, where it was hoped they would provide a cheap food source for slaves. It was a simple shopping trip, but one that seemed to go awry almost immediately. Weather conditions around Cape Horn were so bad that the Bounty was forced to detour across the Indian Ocean, prolonging the journey nearly 10 months. Once the ship finally arrived in Tahiti, the dastardly breadfruit were no longer in season. Bligh and his crew had no choice but to hang out there for five months and await the harvest. Of course, there are worse places to get stuck than Tahiti, and the boys of the Bounty took full advantage of the delay. Bligh allowed his men to live onshore, where they tended the breadfruit plants and “mingled” with the native ladies. Needless to say, discipline lapsed, and when it came time to set sail again, much sulking occurred.

Although bloodless, the incident was far from friendly. Bligh and 18 others were forced into a tiny 23-foot launch boat and abandoned at sea. The group first landed at nearby Tofua, but the island’s inhabitants didn’t take kindly to strangers. One of Bligh’s launchmates was stoned to death by natives, and the exhausted band had to set sail again on May 2. Making like MacGyver, Bligh captained the launch through a harrowing 43-day, 3,600-mile voyage to Timor using only a sextant and a pocketwatch. There, they finally found safe harbor.

Bligh and crew eventually made their way back to England and reported the mutiny on March 16, 1790. Eight months later, the Pandora sailed to Tahiti to find the mutineers and the Bounty (a pursuit that supposedly spawned the term “bounty hunting”). Unfortunately, that mission didn’t go so well, either. After the ship’s crew rounded up 14 stragglers from the Bounty and imprisoned them in a cell (cleverly named “Pandora’s Box”) on the top deck of the ship, the ill-fated Pandora sank on the Great Barrier Reef.

Bligh was eventually tried and acquitted for losing his ship, and he went back to work. In 1791, he received another commission—to collect breadfruit plants. This time, he succeeded in bringing the fruit to the West Indies, but—irony of ironies—the slaves didn’t like the taste and refused to have anything to do with them. Today, breadfruit growers of the world unanimously consider this the funniest thing ever to happen.

Third Course: Fishy Fisticuffs

At first blush, cod don’t seem like provocative creatures. And yet, these bulbous, fleshy fish have brought NATO allies Iceland and Great Britain to the brink of war no fewer than three times in the past 50 years. Unimaginatively, these incidents are popularly known as The Cod Wars.

The root of the problem in all these tiffs has been Iceland’s enormous surplus of nothingness. The frosty island nation has no real fuel, minerals, or agricultural prospects. What they do have is the world’s oldest functioning legislative assembly—the Althing, first convened in 930. But, as anyone who’s tried to eat or sell a functioning legislative assembly will tell you, they bring little to the party. With nowhere to turn but offshore, Iceland turned to fish. In fact, it’s estimated that fish and fish products have long accounted for more than 90 percent of the country’s exports.

The first two Cod Wars (one in 1958 and the other from 1972 to 1973) were sparked when Iceland unilaterally decided to expand its fishing boundaries, arguing that it should be allowed to cordon off any areas deemed fit to protect its chief resource. Great Britain’s counterargument was, in essence, “Hey, we like fish too!” Ultimately, these “wars” were about as mild as cod itself, consisting mostly of threats, net cutting, and lots and lots of salty language.

A ramming incident during the Third Cod War.

No comments:

Post a Comment