A century before Jennifer Lawrence was slinging

arrows as Katniss Everdeen, Helen Holmes invented the female action

hero.

So why have you never heard of her?

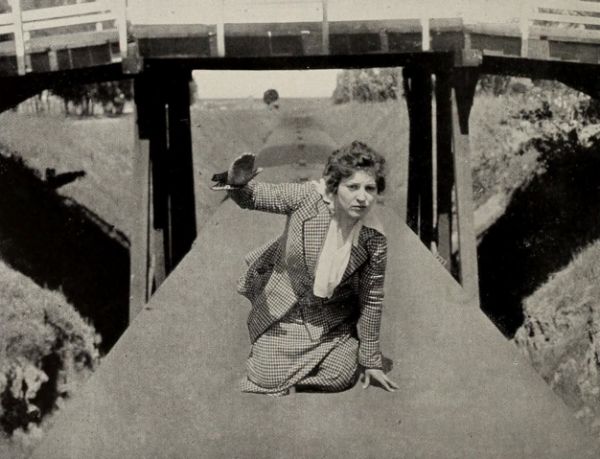

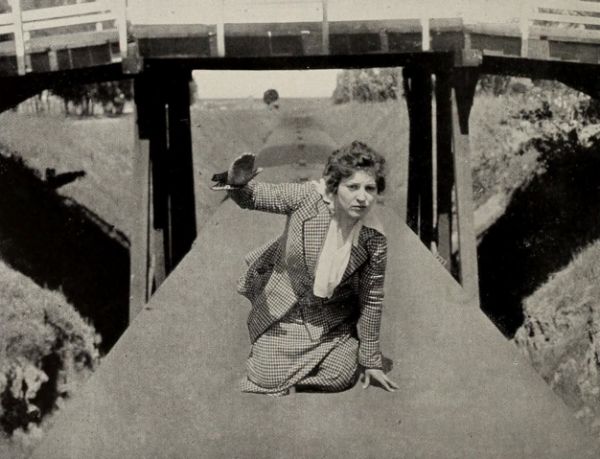

On

the roof of a speeding freight train, a slender woman in a white

feather cap and a long narrow skirt sits crumpled, cradling her head.

Her day’s work is done. A minute ago, she leaped onto this train from a

towering overpass, pointing out two stowaway thieves to the engineers on

duty. As they race to nab the bandits, she doubles over to catch her

breath. The men, she knows, can take it from here.

Suddenly, one

of the thieves appears on the roof. Fresh from a fistfight with the

conductors, the thug tries to rush past her. She scrambles to her feet

and lunges at his waist. They wrestle. He tries to shake her. She

tackles him, and in an instant the two are pitched over the side into

the river below. As they wade from the water, the wet hat still clinging

to her head, she sacks him again, delivering a taste of justice.

It’s a quintessential climax to an episode of the wildly popular 1915 silent film series

The Hazards of Helen.

In a few year’s time, short action flicks like this had become standard

weekend diversions for moviegoing Americans, giving rise to the first

generation of screen stars: Mary Fuller in

What Happened to Mary, Kathlyn Williams in

The Adventures of Kathlyn, and Pearl White in

The Perils of Pauline. These weren’t coy coquettes or damsels in distress; they were action stars racing cars, riding horses, and jumping trains.

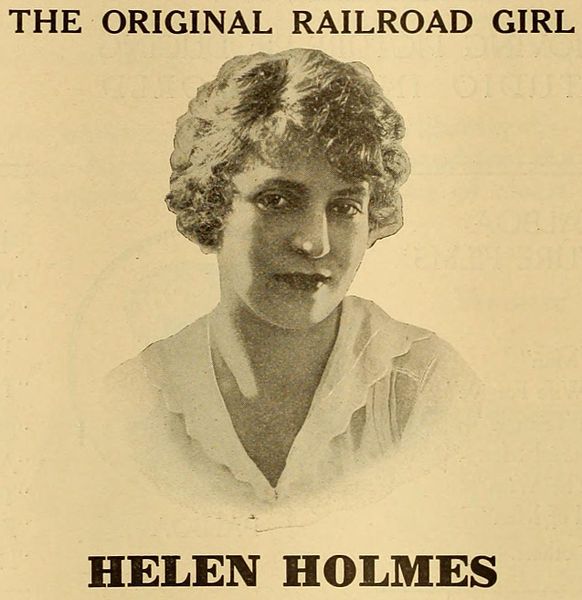

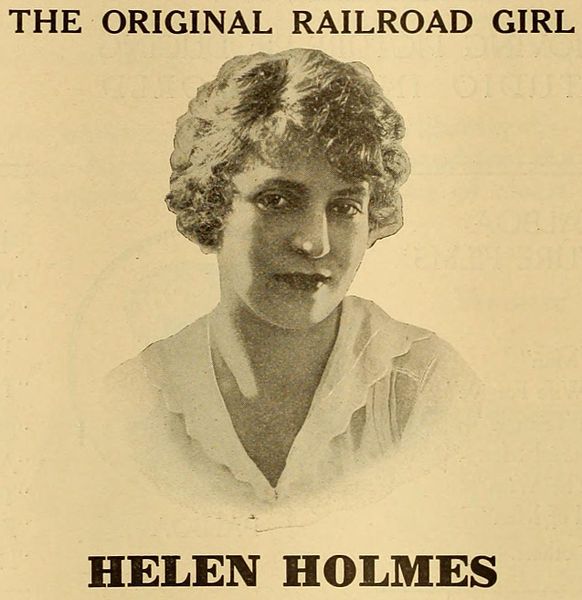

Helen Holmes, the scrapp

y 20-year-old featured in

The Hazards of Helen,

wasn’t the most famous or the most glamorous. But with the women’s

suffrage movement reaching a fever pitch, her no-nonsense handling of

everyday affairs in a man’s world turned her into a fan favorite. What

made her truly revolutionary -even as she faded into obscurity with the

rest of the silent film stars- was what she did behind the scenes.

A Chicago-raised tomboy-turned-model, Holmes was more than just the star of

The Hazards of Helen-

she was, in large part, its creator. Holmes landed her first film roles

in silent comedies in 1912. Shortly after, she joined forces,

personally and professionally, with J.P. “Jack” McGowan, an Australian

director who specialized in short action flicks, most of them one- or

two-reel railroad dramas.

From the start, McGowan and Holmes

wanted to do something different. They envisioned a rough-hewn adventure

series centered on Helen, a railroad operator, who threw herself into

peril in every episode. Production for

Hazards began in

Glendale, California, in 1914, but by early 1915, McGowan had fallen

from a telegraph pole performing a stunt. For six weeks he was in a

plaster cast at the Sisters’ Hospital in Hollywood. That’s when Holmes

took over the production, and she fully embraced the task.

“If

a photoplay actress wants to achieve real thrills, she must write them

into the scenario herself,” she once said. “[N]early all scenario

writers and authors for the films are men, and men usually won’t provide

for a girl things they wouldn’t do themselves. So if I want really

thrilly action, I ask permission to write it for myself.”

Each weekly installment found Helen facing fresh danger, from thieves to runaway trains. In The Wild Engine

(1915), Helen got a job at a railroad, only to have the superintendent

of the company berate the underling who hired her. “Women cannot use

their heads in case of emergency, and if you employ her, I shall hold

you entirely responsible!” Suffice to say, an emergency soon tests the

theory. When an engine goes haywire and sets on a collision course with a

passenger train, Helen jumps on a motorcycle and zooms off to stop it.

She keeps the trains from colliding, of course, but she also rides the

motorcycle off a bridge and into the river to enhance the action. The

film ends with the superintendent changing his stance on Helen’s hiring

-a simplistic story, simplistically told, but one that presents a

radical message by 1915 standards.

Each weekly installment found Helen facing fresh danger, from thieves to runaway trains. In The Wild Engine

(1915), Helen got a job at a railroad, only to have the superintendent

of the company berate the underling who hired her. “Women cannot use

their heads in case of emergency, and if you employ her, I shall hold

you entirely responsible!” Suffice to say, an emergency soon tests the

theory. When an engine goes haywire and sets on a collision course with a

passenger train, Helen jumps on a motorcycle and zooms off to stop it.

She keeps the trains from colliding, of course, but she also rides the

motorcycle off a bridge and into the river to enhance the action. The

film ends with the superintendent changing his stance on Helen’s hiring

-a simplistic story, simplistically told, but one that presents a

radical message by 1915 standards.

In the pre-Hollywood days of

early cinema, moviemaking was defined by a rough-and-tumble DIY

aesthetic. Unlike many of her colleagues, Holmes performed many

death-defying stunts herself, from swinging onto moving locomotives to

crawling across the hoods of speeding cars. She moved with the grace of

an athlete. Asked about her stunt work, she remarked that she sought to

performs stunts without losing “that air of femininity of which we are

all so proud. But by that I do not mean the frail side of a woman. I

mean the heroic side.”

The pace of producing a weekly was

grueling, and it took a toll. “I have a pair of educated knees,” she

said. “I have learned to drop like a kitten. My body is all bruised and

bumped and scarred from the falls I have had.” Reputedly, she nearly

suffered a career-ending injury when she fell off a train face first

into a cactus thicket, puncturing her eye. (After a poisonous thorn was

removed, she fully recovered.)

Holmes

took risks with her body, but she was equally bold with her writing.

Whereas her contemporaries often saw their characters thrust into

jeopardy by chance, Helen’s character plunged into danger intentionally-

after all, it was her job. And while the plots of other series revolved

around romance, the through line of the

Hazards was always Helen’s career and her attempts to prove herself in a treacherous workplace inhabited exclusively by men.

The

themes played nicely to the audience.At the time, moviegoers were

mostly working-class women who went to see serial pictures; they were

the ones Helen was speaking to. There was a growing appetite for

depictions of strong women, and on screen, no female better exemplified

the New Woman ideal than one who could jump trains without breaking the

ostrich brim on her hat.

Before long, Holmes had starred in 46 episodes of

Hazards,

directing at least two. Sadly, her writing and producing credits are

incomplete. For a woman who made her name proving that women could

contribute in the workplace, she never received credit for all the work

she did.

In 1915, Holmes and McGowan left

Hazards to

capitalize on Holmes’ tremendous box-office pull. The series had

rocketed her to national celebrity, and the pair continued to make

adventure films together, and then, after they split in 1918, apart.

Holmes went on to start her own production company, but in a market now

flooded with female action stars, her draw slipped. A payment

disagreement with her distributor added to her woes, contributing to her

first box-office bomb, and she soon gave up screen acting. By the

1920s, a backlash against motion pictures had begun to form. As

filmmakers tested the boundaries of on-screen romance and action,

religious groups began to protest the societal impact. Reformers singled

out weekly serials for corrupting youth and glorifying crime. Some

censorship boards refused to allow films that showed women scrapping

with men and holding their own.

Action

films soon became the exclusive domain of male protagonists, and over

the years, “women’s pictures” came to mean melodramas. And while

American cinema had its share of strong women like Bette Davis and Ida

Lupino, by the ’30s the female action star had essentially ceased to

exist.

Holmes married a stuntman and moved to a cattle ranch in

Sonora, where she began training animals for film. She continued to take

the occasional bit part, and for a time, she served as president of

Riding and Stunt Girls of the Screen, the first organization

established to bargain collectively for stuntwomen. Holmes died in 1950

of pulmonary tuberculosis.

Like the majority of silent cinema, much of Holmes work is lost, but

a handful of the Hazards remain, saved by organizations such as the National Film Preservation Foundation.

Rewatching the films today, Helen Holmes still feels revolutionary. The most daring aspect of

Hazards wasn’t

that her character could tackle a man or leap onto a moving freight

train. It was that Holmes’ heroism came from her being good at her job.

The series dramatized a world where a brave and quick-thinking woman

could prove herself in ways conventionally reserved for men. “Helen

didn’t win an inheritance or a promotion. Her labor and adventures

simply won her respect, camaraderie, and admiration,” feminist scholar

Nan Estad has noted. By embodying Helen with such poised nonchalance,

Holmes helped pave the way for a new kind of character: the female

professional. And while the impact didn’t last long on screen, it was

etched into the minds of those cheering from the seats.

y 20-year-old featured in The Hazards of Helen,

wasn’t the most famous or the most glamorous. But with the women’s

suffrage movement reaching a fever pitch, her no-nonsense handling of

everyday affairs in a man’s world turned her into a fan favorite. What

made her truly revolutionary -even as she faded into obscurity with the

rest of the silent film stars- was what she did behind the scenes.

y 20-year-old featured in The Hazards of Helen,

wasn’t the most famous or the most glamorous. But with the women’s

suffrage movement reaching a fever pitch, her no-nonsense handling of

everyday affairs in a man’s world turned her into a fan favorite. What

made her truly revolutionary -even as she faded into obscurity with the

rest of the silent film stars- was what she did behind the scenes.

Each weekly installment found Helen facing fresh danger, from thieves to runaway trains. In The Wild Engine

(1915), Helen got a job at a railroad, only to have the superintendent

of the company berate the underling who hired her. “Women cannot use

their heads in case of emergency, and if you employ her, I shall hold

you entirely responsible!” Suffice to say, an emergency soon tests the

theory. When an engine goes haywire and sets on a collision course with a

passenger train, Helen jumps on a motorcycle and zooms off to stop it.

She keeps the trains from colliding, of course, but she also rides the

motorcycle off a bridge and into the river to enhance the action. The

film ends with the superintendent changing his stance on Helen’s hiring

-a simplistic story, simplistically told, but one that presents a

radical message by 1915 standards.

Each weekly installment found Helen facing fresh danger, from thieves to runaway trains. In The Wild Engine

(1915), Helen got a job at a railroad, only to have the superintendent

of the company berate the underling who hired her. “Women cannot use

their heads in case of emergency, and if you employ her, I shall hold

you entirely responsible!” Suffice to say, an emergency soon tests the

theory. When an engine goes haywire and sets on a collision course with a

passenger train, Helen jumps on a motorcycle and zooms off to stop it.

She keeps the trains from colliding, of course, but she also rides the

motorcycle off a bridge and into the river to enhance the action. The

film ends with the superintendent changing his stance on Helen’s hiring

-a simplistic story, simplistically told, but one that presents a

radical message by 1915 standards.

Action

films soon became the exclusive domain of male protagonists, and over

the years, “women’s pictures” came to mean melodramas. And while

American cinema had its share of strong women like Bette Davis and Ida

Lupino, by the ’30s the female action star had essentially ceased to

exist.

Action

films soon became the exclusive domain of male protagonists, and over

the years, “women’s pictures” came to mean melodramas. And while

American cinema had its share of strong women like Bette Davis and Ida

Lupino, by the ’30s the female action star had essentially ceased to

exist.

No comments:

Post a Comment