At Xmas Time

I

"What shall I write?" asked Yegor,

dipping his pen in the ink.

Vasilissa had not seen her daughter for four

years. Efimia had gone away to St. Petersburg

with her husband after her wedding, had written

two letters, and then had vanished as if the earth

had engulfed her, not a word nor a sound had come

from her since. So now, whether the aged mother

was milking the cow at daybreak, or lighting the

stove, or dozing at night, the tenor of her

thoughts was always the same: "How is Efimia?

Is she alive and well?" She wanted to send

her a letter, but the old father could not write,

and there was no one whom they could ask to write

it for them.

But now Xmas had come, and Vasilissa could

endure the silence no longer. She went to the

tavern to see Yegor, the innkeeper's wife's

brother, who had done nothing but sit idly at home

in the tavern since he had come back from military

service, but of whom people said that he wrote the

most beautiful letters, if only one paid him

enough. Vasilissa talked with the cook at the

tavern, and with the innkeeper's wife, and finally

with Yegor himself, and at last they agreed on a

price of fifteen copecks.

So now, on the second day of the Xmas

festival, Yegor was sitting at a table in the inn

kitchen with a pen in his hand. Vasilissa was

standing in front of him, plunged in thought, with

a look of care and sorrow on her face. Her

husband, Peter, a tall, gaunt old man with a bald,

brown head, had accompanied her. He was staring

steadily in front of him like a blind man; a pan

of pork that was frying on the stove was sizzling

and puffing, and seeming to say: "Hush, hush,

hush!" The kitchen was hot and close.

"What shall I write?" Yegor asked

again.

"What's that?" asked Vasilissa,

looking at him angrily and suspiciously.

"Don't hurry me! You are writing this letter

for money, not for love! Now then, begin. To our

esteemed son-in-law, Andrei Khrisanfltch, and our

only and beloved daughter Efimia, we send

greetings and love, and the everlasting blessing

of their parents."

"All right, fire away!"

"We wish them a happy Xmas. We are

alive and well, and we wish the same for you in

the name of god, our Father in heaven--our Father

in heaven--"

Vasilissa stopped to think, and exchanged

glances with the old man.

"We wish the same for you in the name of god, our Father in Heaven--" she repeated and

burst into tears.

That was all she could say. Yet she had

thought, as she had lain awake thinking night

after night, that ten letters could not contain

all she wanted to say. Much water had flowed into

the sea since their daughter had gone away with

her husband, and the old people had been as lonely

as orphans, sighing sadly in the night hours, as

if they had buried their child. How many things

had happened in the village in all these years!

How many people had married, how many had died!

How long the winters had been, and how long the

nights!

"My, but it's hot!" exclaimed Yegor,

unbuttoning his waistcoat. "The temperature

must be seventy! Well, what next?" he asked.

The old people answered nothing.

"What is your son-in-law's

profession?"

"He used to be a soldier, brother; you

know that," replied the old man in a feeble

voice. "He went into military service at the

same time you did. He used to be a soldier, but

now he is in a hospital where a doctor treats sick

people with water. He is the door-keeper

there."

"You can see it written here," said

the old woman, taking a letter out of her

handkerchief. "We got this from Efimia a

long, long time ago. She may not be alive

now."

Yegor reflected a moment, and then began to

write swiftly.

"Fate has ordained you for the military

profession," he wrote, "therefore we

recommend you to look into the articles on

disciplinary punishment and penal laws of the war

department, and to find there the laws of

civilisation for members of that department."

When this was written he read it aloud whilst

Vasilissa thought of how she would like to write

that there had been a famine last year, and that

their flour had not even lasted until Xmas,

so that they had been obliged to sell their cow;

that the old man was often ill, and must soon

surrender his soul to god; that they needed

money--but how could she put all this into words?

What should she say first and what last?

"Turn your attention to the fifth volume

of military definitions," Yegor wrote.

"The word soldier is a general appellation, a

distinguishing term. Both the commander-in-chief

of an army and the last infantryman in the ranks

are alike called soldiers--"

The old man's lips moved and he said in a low

voice:

"I should like to see my little

grandchildren!"

"What grandchildren?" asked the old

woman crossly. "Perhaps there are no

grandchildren."

"No grandchildren? But perhaps there are!

Who knows?"

"And from this you may deduce," Yegor

hurried on, "which is an internal, and which

is a foreign enemy. Our greatest internal enemy

is Bacehus--"

The pen scraped and scratched, and drew long,

curly lines like fish-hooks across the paper.

Yegor wrote at full speed and underlined each

sentence two or three times. He was sitting on a

stool with his legs stretched far apart under the

table, a fat, lusty creature with a fiery nape and

the face of a bulldog. He was the very essence of

coarse, arrogant, stiff-necked vulgarity, proud to

have been born and bred in a pot-house, and

Vasilissa well knew how vulgar he was, but could

not find words to express it, and could only glare

angrily and suspiciously at him. Her head ached

from the sound of his voice and his unintelligible

words, and from the oppressive heat of the room,

and her mind was confused. She could neither

think nor speak, and could only stand and wait for

Yegor's pen to stop scratching. But the old man

was looking at the writer with unbounded

confidence in his eyes. He trusted his old woman

who had brought him here, he trusted Yegor, and,

when he had spoken of the hydropathic

establishment just now, his face had shown that he

trusted that, and the healing power of its waters.

When the letter was written, Yegor got up and

read it aloud from beginning to end. The old man

understood not a word, but he nodded his head

confidingly, and said:

"Very good. It runs smoothly. Thank you

kindly, it is very good."

They laid three five-copeck pieces on the table

and went out. The old man walked away staring

straight ahead of him like a blind man, and a look

of utmost confidence lay in his eyes, but

Vasilissa, as she left the tavern, struck at a dog

in her path and exclaimed angrily:

"Ugh--the plague!"

All that night the old woman lay awake full of

restless thoughts, and at dawn she rose, said her

prayers, and walked eleven miles to the station to

post the letter.

II

Doctor Moselweiser's hydropathic establishment

was open on New Year's Day as usual; the only

difference was that Andrei Khrisaufitch, the

doorkeeper, was wearing unusually shiny boots and

a uniform trimmed with new gold braid, and that he

wished every one who came in a happy New Year.

It was morning. Andrei was standing at the

door reading a paper. At ten o'clock precisely an

old general came in who was one of the regular

visitors of the establishment. Behind him came

the postman. Andrei took the general's cloak, and

said:

"A happy New Year to your

Excellency!"

"Thank you, friend, the same to you!"

And as he mounted the stairs the general nodded

toward a closed door and asked, as he did every

day, always forgetting the answer:

"And what is there in there?"

"A room for massage, your

Excellency."

When the general's footsteps had died away,

Andrei looked over the letters and found one

addressed to him. He opened it, read a few lines,

and then, still looking at his newspaper,

sauntered toward the little room down-stairs at

the end of a passage where he and his family

lived. His wife Efimia was sitting on the bed

feeding a baby, her oldest boy was standing at her

knee with his curly head in her lap, and a third

child was lying asleep on the bed.

Andrei entered their little room, and handed

the letter to his wife, saying:

"This must be from the village."

Then he went out again, without raising his

eyes from his newspaper, and stopped in the

passage not far from the door. He heard Efimia

read the first lines in a trembling voice. She

could go no farther, but these were enough. Tears

streamed from her eyes and she threw her arms

round her eldest child and began talking to him

and covering him with kisses. It was hard to tell

whether she was laughing or crying.

"This is from granny and granddaddy,"

she cried-- "from the village--oh, Queen of

Heaven!-- Oh! holy saints! The roofs are piled

with snow there now--and the trees are white, oh,

so white! The little children are out coasting on

their dear little sleddies--and granddaddy

darling, with his dear bald head is sitting by the

big, old, warm stove, and the little brown

doggie--oh, my precious chickabiddies--"

Andrei remembered as he listened to her that

his wife had given him letters at three or four

different times, and had asked him to send them to

the village, but important business had always

interfered, and the letters had remained lying

about unposted.

"And the little white hares are skipping

about in the fields now--" sobbed Efimia,

embracing her boy with streaming eyes.

"Granddaddy dear is so kind and good, and

granny is so kind and so full of pity. People's

hearts are soft and warm in the village-- There is

a little church there, and the men sing in the

choir. Oh, take us away from here, Queen of

Heaven! Intercede for us, merciful mother!"

Andrei returned to his room to smoke until the

next patient should come in, and Efimia suddenly

grew still and wiped her eyes; only her lips

quivered. She was afraid of him, oh, so afraid!

She quaked and shuddered at every look and every

footstep of his, and never dared to open her mouth

in his presence.

Andrei lit a cigarette, but at that moment a

bell rang up-stairs. He put out his cigarette,

and assuming a very solemn expression, hurried to

the front door.

The old general, rosy and fresh from his bath,

was descending the stairs.

"And what is there in there?" he

asked, pointing to a closed door.

Andrei drew himself up at attention, and

answered in a loud voice:

"The hot douche, your Excellency."

After

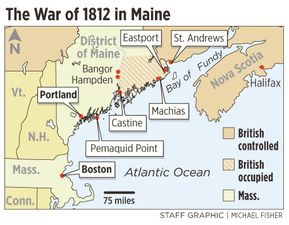

Napoleon abdicated in 1814, Britain began a series of offensives

designed to bring about victory over the Americans in the War of 1812.

Among them was an

After

Napoleon abdicated in 1814, Britain began a series of offensives

designed to bring about victory over the Americans in the War of 1812.

Among them was an  Naval

expeditions under Sir John Sherbrooke (left) and his subordinates

captured the coastal towns of Eastport, Machias and Castine, then sailed

inland up the Penobscot River, capturing Hampden and Bangor. Sherbrooke

declared that Maine east of the Penobscot was now a British colony

named New Ireland.

Naval

expeditions under Sir John Sherbrooke (left) and his subordinates

captured the coastal towns of Eastport, Machias and Castine, then sailed

inland up the Penobscot River, capturing Hampden and Bangor. Sherbrooke

declared that Maine east of the Penobscot was now a British colony

named New Ireland.