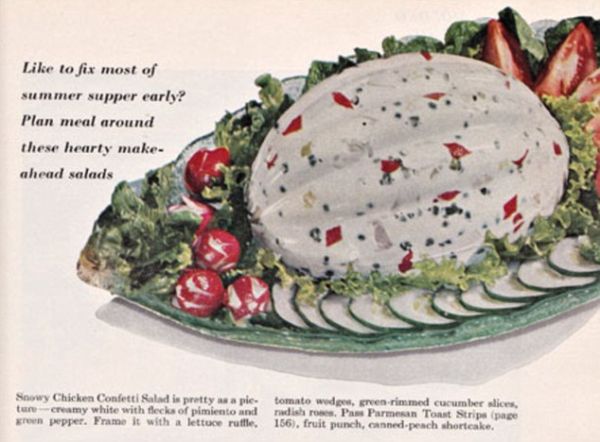

French researchers try to date the Codex Borbonicus, one of the most treasured Mesoamerican historical documents

Detail from the Codex Borbonicus – the goddess Chalchiuhtlicue, symbol of Venus.

It was May 1826 and France was celebrating the first anniversary of

the coronation of Charles X. French troops had occupied Spain;

Mexico

had gained its independence and Latin America was in turmoil. But,

sitting in his office in the library of the National Assembly,

deputy-curator Pierre-Paul Druon was feeling pleased. For the past 30

years this former Benedictine monk had labored to track down rare works

and add them to the 12,000 items inherited from the French Revolution

and now entrusted to parliament. Never before had he had the opportunity

to acquire such a treasure, even if the source of the Nahuatl

manuscript he purchased for 1,300 gold francs at auction was unknown and

two of its pages were missing. He was, nevertheless, convinced of its

worth.The document, in its present state, is 14 meters long, comprising 36

fan-folded sheets, each 39 sq cm. It details the cycles of two

calendars, one divinatory, the other solar, used by the Aztecs before

the

Spanish conquest led by Hernán Cortés in 1519. It represents several hundred brightly colored figures and creatures, each of particular significance.

Here “lords of the night” and “numbers”, accompanied by glyphs, “day

signs” and ritual birds, surround the deities who preside over the 20

13-day weeks in the “book of destinies”. There Cipactonal and his wife,

Oxomoco, the first couple on Earth, celebrate the festival of the “new

fire”, which marks the moment when the two systems coincide, every 52

years. Then come the religious ceremonies associated with the 18 20-day

months that make up a year.

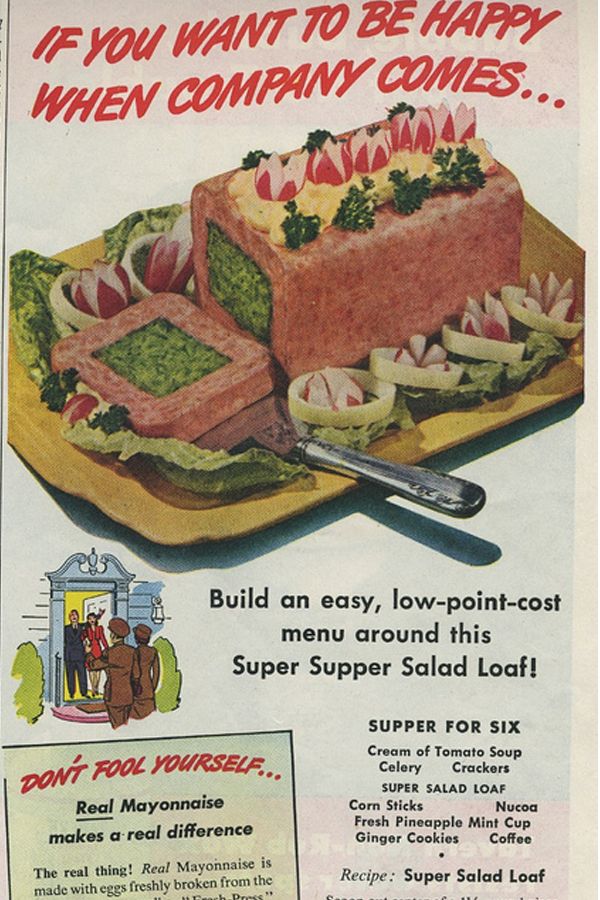

Here again, priests wearing flayed human skins, desiccated hands

falling loose at their wrists, present scepters and shields to

sacrificial victims who will be skinned to hail new growth. Elsewhere

they dance round the ritual xocotl tree, in an end-of-year offering to

the flowers.

This extraordinary document, referred to as the

Codex Borbonicus

in reference to the Palais Bourbon, seat of the lower house of the

French parliament, is one of France’s national treasures. It is one of

six documents – an original parchment dating from the trial of Joan of

Arc, a ninth-century Bible, two Rousseau manuscripts and the

Serment du Jeu de Paume

(Tennis Court oath) – that have not been allowed out of the country

since the 1960s. Does it predate Cortés? Or, as suggested by the

catalog of a 2008 exhibition at Quai Branly, is it a colonial-era

manuscript, resulting from the clash between Meso-American and western

cultures?

Now, 188 years after the manuscript’s first public appearance,

specialists from the Natural History Museum in Paris, the National

Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS) and the arts ministry are trying

to answer that question.

In May 2013 an “exceptional” decision by MPs authorized the experts

to analyze the materials used in the Codex in an attempt to date it.

This is a technical and scientific challenge in itself, because the

research must be carried out in a strong room under the parliament, at a

constant temperature of 18C.

Detail from the Codex Borbonicus, showing Quetzalcoatl, the mythical Aztec feather serpent.

Interest in the Codex goes beyond conservation. Pre-Columbian

documents describing the beliefs and rites of Mesoamerican

civilizations, between central Mexico and Costa Rica, are extremely

rare. Very few survived the Spanish inquisition. From 1525, in order to

speed up conversion of the “Indians”, their temples were demolished and

their “idolatrous” books banned. In 1562, for example, 27 “demoniac”

documents were burned at Mani, Yucatan, and their owners put to death.According to historical accounts, when Cortés and his companions

entered the Aztec capital Tenochtitlan on 8 November 1519, they found

libraries containing thousands of works on many subjects. Now only about

20 pre-Columbian Mesoamerican documents remain. Only five of these,

belonging to the Borgia group, are categorically genuine. The majority

of them have been shown to be of Mayan or Mixtecan origin. None were

produced by the Aztec empire or in its main language, Nahuatl.

What does remain are roughly 500 “colonial” manuscripts, some drafted by

tlacuilos,

or indigenous scribes, between the 16th and 18th century on the

instructions of the authorities in New Spain. The aim was to gain a

better understanding of the history and customs of the native peoples

the Spanish sought to govern and convert. Some of these documents – such

as the Florentine Codex begun in 1547 under the supervision of the

Franciscan missionary Bernardino de Sahagún – were designed with the

help of scholars familiar with the Nahuatl language and were real

encyclopedias. They were packed with information on the Aztecs, the

“people of the Sun” who came from the north and for 200 years leading up

to 1521 took possession of the Mexican plateau. They took their

spiritual lead from Huitzilopochtli (held by some to mean “left-handed

hummingbird”), a deity who demanded that his people wage war to provide

human sacrifices, thus feeding the sun with blood to sustain its daily

journey.

Where does the Codex Borbonicus fit in? The commonly accepted explanation is that the French stole it from the library at the

Escorial palace,

outside Madrid, when Napoleon’s army invaded Spain in 1808. But there

is no proof of this and the year of its purchase by the French

parliament, 1826, coincides with unrest in Latin America, which may

explain why the manuscript came up for sale in Europe.

Analysis of the Codex’s contents is more helpful. According to

several specialists, such as anthropologist Ernest Théodore Hamy who

made a facsimile copy in 1899, it is pre-Columbian and may date back to

1507. But other experts maintain that it is a copy of a pre-colonial

original. They cite its size – larger than other known codices, which

were designed to be portable – the grid pattern on some pages and empty

spaces set aside for comments in Spanish. Some go so far as to claim

that a particular scene represents the crucifixion. If it is a copy, it

would have been produced just after the Spanish conquest, but using

traditional techniques. Pointing out the differences in style and color

between the first and second part of the codex, some commentators have

suggested that it is a composite work, either finished after the

conquest or a marriage of two distinct works.

However, on two points there is consensus: the Codex Borbonicus was

the work of Aztecs, perhaps even based in their capital; and it is

essential to an understanding of how all the Mesoamerican civilizations

of that period represented time.

Jointly funded by the

Foundation for Cultural Heritage Sciences

(FSP) and France’s National Assembly, the new research program hopes

to find out whether the whole manuscript was produced using traditional

methods. If not, it may contain traces of materials imported from Europe

by the Spanish. “It is impossible to date the Codex directly,” says

Fabien Pottier, a PhD student working on the subject. “We’re interested

in knowing whether it was made just before or just after Cortés arrived

in 1519, which means a window of between 20 and 40 years at the most.

None of the known dating techniques, even using carbon-14, is accurate

enough for that.”

Instead, the Patrimex system is being used. There is only one in

France

and it all fits into a van and is mobile for “analyzing monuments or

objects which cannot be moved”, says FSP general-secretary Emmanuel

Poirault.

Work started on the manuscript at the beginning of September. The

Patrimex hyperspectral imaging system operates in a series of spectral

bands ranging from the visible to infra-red and will photograph the

Codex in 900 bands. With digital processing, researchers should be able

to discover the characteristic spectrum of each organic dye and the

paper itself, probably

amate. This was made with fig-tree bark

coated with gypsum. By comparing individual pages, and others made using

traditional techniques but artificially aged in a laboratory, the

scientists hope to settle the question of European input.

“Of course people could always say that even if they had no part in

making the document itself, the Spanish influenced the process simply by

being present,” says José Contel, from Toulouse University. Would this

be a recognition of failure? “Not at all,” says Elodie Dupey Garcia, a

CNRS researcher currently in Mexico City. “In the last few years we have

begun to realize that in Mesoamerican civilizations there is a symbolic

side to every technique, over and above its practical value,” she

explains. “They deliberately used pigments obtained from hard-to-find

plants or animals (such as cochineal for scarlet, or Mayan indigo)

despite having ready access to a whole range of mineral dyes. Organic

pigments have a special texture and brilliance that suited the aesthetic

standards of the Aztecs – a beautiful color should be bright. So

confirming that the Codex Borbonicus, the only Aztec manuscript we have

that might be pre-Columbian, was really made in the traditional way

would be really great news. Much more important than finding out it was

produced just before or just after Cortés reached Mexico.”