In proposing that Incans practiced brain surgery—something even the

best European and American doctors struggled with—and positing that

ancient American civilizations were as advanced as ancient Egypt and

Rome, Squier was gambling with his reputation. At the time, there was a

pervasive prejudice against Amerindian tribes, who had long been

dismissed as loin-clothed savages wielding crude tools. This was

tangible proof otherwise. And Squier was willing to do anything—cross

colleagues, forgo his dignity, sacrifice his marriage—to make the rest

of the world understand.

The Guano Problem

The funny thing

is, Squier hadn’t traveled to South America to learn more about

ancient neurosurgery or to combat stereotypes. No, Squier had come to

South America to settle something far more serious: an argument about

bird poop.

Throughout the 1800s, farmers used natural fertilizers

to grow crops. The best fertilizers came from islands off South

America, where mountains of guano had piled up over eons. Guano proved

so important to global health and economics—millions of dollars were at

stake, not to mention the health of millions of hungry people—that

Chile, Bolivia, and Peru actually went to war over bird excrement in

1879.

For

most of the 1800s, the U.S. imported thousands of tons of guano per

year, and with the outbreak of the Civil War in the 1860s, securing

fertilizer to help guarantee a steady supply of food became a necessity.

But a number of international incidents (one involving Confederate

pirates seizing Peruvian ships and destroying guano cargo) had angered

Peru, and the government was threatening to cut off the pipeline. The

situation forced Abraham Lincoln to address the United States’ guano

deficit head on. He dispatched a delegation to Peru in July 1863, and

Squier, who had served as a diplomat in Central America, was a natural

choice.

Squier spent five months untangling the legal claims in

Peru. Having succeeded, he then sent his wife, Miriam, home to New York

and set out to explore his real interest, the country’s buried

artifacts and vine-choked ruins. Over the next 18 months, he traveled

everywhere from the coast of Peru to the peaks of the Andes deep in the

interior. He saw mountain fortresses, llamas, and statues and

artifacts of every kind. The trip culminated with a visit to Señora

Zentino, which was when the idea of ancient neurosurgery grabbed him.

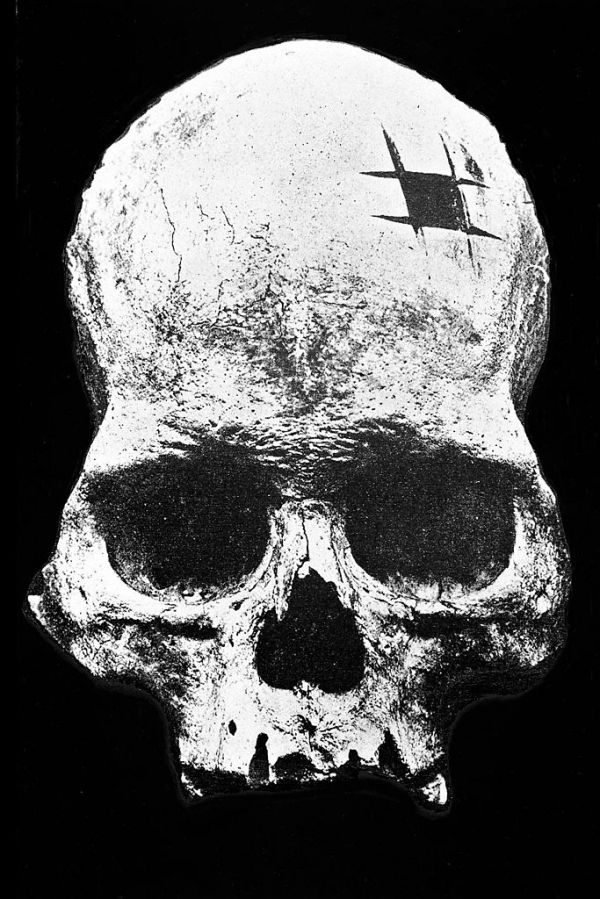

Squier

saw the holes as evidence of trepanation—a procedure in which surgeons

cut out a pocket of the skull to relieve internal pressure and remove

sharp fragments of bone. Western doctors had been trepanning skulls as

far back as ancient Greece, and it had a brutal reputation. Medieval

doctors plugged patients’ ears with lint so they couldn’t hear their

own heads being sawed open. Few people who endured trepanation

survived. By 1700, most clinics had abandoned the procedure. As one

British surgeon declared in 1839, any doctor who proposed trepanning

someone “ought to be trepanned in turn.”

Squier’s

claim, then, seemed iffy—if the best European surgeons couldn’t pull

off trepanations, how could so-called primitive jungle tribes? But

Squier was convinced. After returning to New York in 1865, he showed

the skull to colleagues and outlined his theory. In the debate that

followed, some sided with Squier, while others derided the idea.

Undeterred,

Squier appealed to the highest scientific authority around, French

neurologist Paul Broca. Broca had recently achieved worldwide fame by

discovering the first-known language center in the brain, now called

Broca’s area. The Frenchman shared Squier’s passion for archaeology,

especially for skulls, and in 1867, he snapped up Squier’s offer to

examine the Incan skull.

Broca’s conclusions were unequivocal:

Squier was correct. The shape of the hole could not have been natural

or accidental, and he confirmed that new bone had grown around the rim.

Broca’s medical eye also found signs of inflammation, further evidence

that the patient had survived.

Broca forced scientists in Europe

to confront the possibility that ancient people had developed their own

sophisticated medical practices. Soon, other archaeologists started to

notice trepanned skulls in their collections, some potentially dating

back 10,000 years. Most of the holes were small and circular, but some

gaped as wide as five inches across. Many had rims completely smoothed

over by new bone growth, indicating that the patients had lived for

years after. Skulls with multiple trepanations even turned up. One

unlucky Incan fellow had seven separate holes in his head, all

perfectly healed. But as archaeologists embraced Squier’s theory, a

bigger mystery emerged: Why were civilizations performing trepanations

in the first place?

Trepanation: A How-To Guide

Before

they could tackle why, archaeologists needed to understand how. Over

the years, Incan pots with images of trepanations had turned up.

Additionally, evidence from rural Kenya, New Guinea, and similarly

remote areas showed that other tribes were also proficient in the

practice.

The procedure looked something like this: Imagine a

young warrior hit in the head with a slingshot stone, which left a

crater of mangled bone. A surgeon would clamp the young man’s head

between his knees, crack open a coconut, and pour the juice on the

scalp. The doctor, meanwhile, would dab fresh-cut leaves on the wound

to dull the pain.

Then he’d get to work,

using a shark tooth or something sharp to cut into the skull, grooving

it round and round the depressed fracture, carefully working the

incision deeper. Throughout the process, the warrior would gulp alcohol

or consume tobacco to quell the discomfort. He would feel almost

nothing after the initial pain: just the friction of the shark tooth

against his skull. At last, the warrior would experience a slight

sucking sensation as a plug of skull bone came free. With bamboo

fashioned into forceps, the surgeon would pick out the bone splinters

and wash the wound with coconut milk. He’d sew up the scalp with a

needle and thread made of bat bones and banana fibers. A dressing of

leaves and a plaster of pepper, lime, and betel nut might seal the

wound. Finally, the patient would be instructed to eat soft foods for a

week and minimize the movement of his head.

As

with today’s procedures, managing pain and infection were the biggest

concerns, but surgeons had measures to combat these. The coca leaves

helped anesthetize the skull. Similarly, wild plants like balsam killed

bacteria, as did washing wounds with coconut milk. In fact, ancient

surgeons did a remarkable job with sterilization: In one study of 66

trepanned skulls, just three showed any signs of infection. These

surgeons had a better track record than their counterparts in

industrialized countries. In one survey from London in the 1870s, 75

percent of neurosurgical patients died, mostly due to infections.

Compare that to the New Guinea tribes, where surgeons lost just 30

percent of their patients.

THE SPIRIT THEORY

Why ancient

cultures performed neurosurgery remains controversial. After years of

studying skull holes, Broca concluded that doctors had trepanned skulls

primarily to release spirits trapped inside the brain. Moreover, he

hypothesized that they operated mostly on children, a claim he based on

a macabre experiment. Using sharp glass, Broca managed to open the

skull of a recently deceased 2-year-old in four minutes. Cutting a

similar hole in an adult skull required 50 minutes, and his hand ached.

Broca concluded that ancient surgeons lacked the patience and tools to

cut through adult skulls and therefore must have limited the procedure

to children, who grew up with holes in their heads.

But most

scientists doubt Broca’s conclusion, partially because few trepanned

child skulls have ever turned up. Broca’s theory that trepanation

released evil spirits, however, proved enormously influential. This

idea played into stereotypes of ancient people. And, in truth, many

tribes—despite wildly different supernatural beliefs—probably did

trepan people to treat epilepsy and hallucinations, maladies often

associated with spirits.

Squier and other archaeologists always

doubted the spirit theory, however. They promoted an alternative: that

ancient neurosurgeons were removing bone fragments from injuries

sustained during combat. Modern research has provided strong evidence

for this, especially among the Inca. For one thing, far more males than

females had trepanation holes, likely because most warriors were

males. For another, the holes were usually located on the left side of

the skull—where a right-handed assailant would aim a slingshot or smash

his club.

From a modern medical perspective, the idea makes

sense: Doctors today still trepan people to reduce pressure on the

brain after injury. The practice is meant to reduce swelling and the

buildup of blood and other fluids, which can kill brain cells.

In

the end, Squier bested Broca in the debate over why ancient

neurosurgeons cut open skulls. But while Broca continued to have a

glorious career, Squier’s unraveled not long after his discovery—as if

the skull really were cursed.

Sad State of Squier's Affairs

It

all started when Squier sent his wife, Miriam, home from Peru after

the guano affair. Alone and resentful, Miriam accepted a job editing

magazines for publisher Frank Leslie, and the two became inseparable.

After his divorce in 1866, Leslie moved in with her and Squier. This

seemed suspicious enough, but things really turned nasty in 1867 when

the trio took a trip to Liverpool. Squier had some outstanding debts in

England, and, humiliatingly, the police arrested him the moment he

stepped ashore. An “anonymous” tipster—likely Leslie—had wired ahead to

alert his creditors. With Squier out of the way, Leslie and Miriam’s

affair began in earnest.

In May 1873, Miriam finally divorced

Squier after publicly accusing him of sleeping with two prostitutes.

Free of her husband, Miriam married Leslie in July 1874—a betrayal that

broke Squier’s spirit. Just one month later, he had deteriorated to

the point that a judge temporarily committed him to an insane asylum.

Squier died at his brother’s home in Brooklyn in 1888. He was 67.

It

was a sad, sordid end for one of America’s greatest archaeologists.

Still, Squier did accomplish his life’s goal. He hadn’t thought much of

Lincoln’s assignment in 1863, grumbling that guano “has contributed

more towards the corruption of [Peru] than any one other thing.” But

his trip to South America—and his willingness to take seriously a

funny-looking hole in an old skull—revolutionized our understanding of

ancient medicine, showing the world that, sometimes, a hole in the head

is a sign of sophistication.