Most stories have the moral at the end. But we’ll put it right up front: If it seems too good to be true, it probably is.

NIGHT DEPOSIT

One

evening in February 1871, George Roberts, a prominent San Francisco

businessman, was working in his office when two men came to his door.

One of them, Philip Arnold, had once worked for Roberts; the other was

named John Slack. Arnold produced a small leather bag and explained that

it contained something very valuable; as soon as the Bank of California

opened in the morning, he was going to have them lock it in the vault

for safekeeping.

Arnold and Slack made a show of not wanting to

reveal what was in the bag, but eventually told Roberts that it

contained “rough diamonds” they’d found while prospecting on a mesa

somewhere in the West. They wouldn’t say where the mesa was, but they

did say it was the richest mineral deposit they’d ever seen in their

lives: The site was rich not only in diamonds, but also in sapphires,

emeralds, rubies, and other precious stones.

The story sounded

too good to be true, but when Arnold dumped the contents of the bag onto

Robert’s desk, out spilled dozens of uncut diamonds and other gems.

PAY DIRT

If

someone were to make such a claim today, they’d probably get laughed

out of the room. But things were different in 1871. Only 20 years had

passed since the discovery of gold at Sutter’s Mill in California spiked

the greatest gold rush in American history. Since then other huge gold

deposits had been discovered in Colorado, as well as in Australia and

New Zealand. A giant vein of silver had been found in the famous

Comstock Lode in Nevada in 1859, and diamonds had been discovered in

South Africa in 1867- just four years earlier. Gems and precious metals

might be anywhere, lying just below the earth’s surface, waiting to be

discovered. People who’d missed out on the earlier bonanzas were hungry

for word of new discoveries, and the completion of the transcontinental

railroad in 1869 opened up the West and create the expectation that more

valuable strikes were just around the corner. When Arnold and Slack

rolled into town with their tale of gems on a mesa and a bag of precious

stones to back it up, people were ready to believe them.

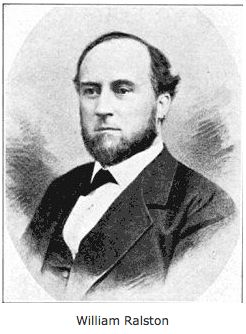

OPEN SECRET

The

next morning the two men went to the Bank of California and deposited

their bag in the bank’s vault. They made another big show of not wanting

anyone to know what was in the bag, and again they let some of the bank

employees have a peek. Soon everyone in the bank knew what was in it,

including the president and founder, William Ralston. He had made a

fortune off the Comstock Lode, and had his eye out for the next big

find. Ralston didn’t keep the men’s secret, and neither did George

Roberts: Soon all of San Francisco, the city built by the Gold Rush of

1849, was buzzing with the tale of the two miners and their discovery.

Arnold and Slack left town for a few weeks, and when they returned,

they claimed they’d made another trip to their diamond field. And they

had another big bag of gems to prove it. Ralston knew a good thing when

he saw it and immediately began lining up the cream of San Francisco’s

investment community to buy the mining claim outright. While Arnold

played hard to get, Slack agreed to sell his share of the diamond field

for $100,000, the equivalent of several million dollars today. Slack

received $50,000 up front and was promised another $50,000 when he

brought more gems from the field.

Arnold and Slack left town

again, and several weeks later returned with yet another bulging sack of

precious stones. Ralston immediately paid Slack the remaining $50,000.

BIG TIME

Ralston

didn’t know it, but he was being had. The uncut gems were real enough,

but the story of the diamond field was a lie. Arnold and Slack had

created a fake mining claim in Colorado by sprinkling, or “salting” it

with diamonds and other gems where miners would be able to find them. It

was a common trick designed to make otherwise worthless land appear

valuable. What made this deception different was its scale and the

caliber of people who were taken in by it. Ralston was a prominent and

successful banker; he and his associates were supposed to be shrewd

investors.

DUE DILIGENCE

To the

investor’s credit, they did take some precautions that they thought

would protect them from fraud: Before any more money changed hands, they

insisted on having a sample of the stones appraised by the most

respected jeweler in the United States— none other than New York City’s

Charles Tiffany. If the appraisal went well, they planned to send a

mining engineer out to the diamond field to verify first, that it

existed, and second, that it was as rich as Arnold and Slack claimed.

These precautions should have been enough, but through a combination of

poor judgment and bad luck, they both failed miserably.

MAKE NO MISTAKE

In

October 1871, Ralston brought a sample of the gems to New York so

Tiffany could look them over. Ralston was already hard at work drumming

up potential investors on the East Coast, and present at the appraisal

were one U.S. Congressman and two former Civil War generals, including

George McClellan, who’d run for president against Abraham Lincoln in

1864. Horace Greeley, editor of the New York Times, was also there.

Tiffany’s

expertise was actually in cut and polished diamonds— he knew almost

nothing about uncut stones, and neither did his assistant. But he didn’t

let anyone else in the room know that. Instead, he made a solemn show

of studying the gems carefully through an eyepiece, and then announced

to the assembled dignitaries, “Gentlemen, these are beyond question

precious stones of enormous value.”

The investors accepted the claim at face value -the appraiser, after all was Charles Tiffany.

Two days later, Tiffany's assistant pegged the value of the sample at

$150,000, which, if true (it wasn’t), meant the total value of all the

stones found so far was $1.5 million (in today’s money, $21 million) …or

more.

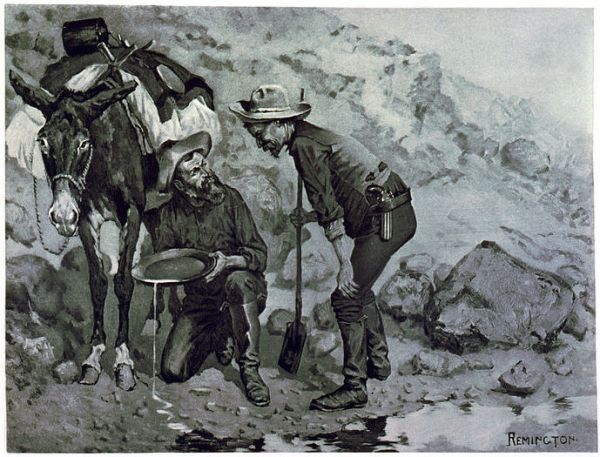

IN THE FIELD

Now

that the gems had been verified as authentic, it was time to send an

independent expert out to the diamond field to confirm that it was

everything Arnold and Slack said it was. As he’d done when he brought

the stones to Tiffany, Ralston went with the most qualified expert he

could find. He hired a respected mining engineer named Henry Janin to do

the job. Janin had inspected more than 600 mines and had never made a

mistake. His first goof would prove to be a doozy.

Janin, Arnold,

Slack, and three of the investors traveled by train to Wyoming, just

over the border from Colorado. Then they made a four-day trek by

horseback into the wilderness, crossing back into Colorado. At Arnold

and Slack’s insistence, Janin and the investors rode blindfolded to keep

them from learning the location of the diamond field.

The men

arrived at the mesa on June 4, 1872, and began looking in a location

suggested by Arnold. A few minutes was all it took: One of the investors

screamed out loud and held up a raw diamond that he’d discovered

digging in some loose dirt. “For more than an hour, diamonds were found

in profusion,” one of the investors later wrote, “together with

occasional rubies, emeralds, and sapphires. Why a few pearls weren’t

thrown in for good luck I have never yet been able to tell. Probably it

was an oversight.”

SEEING IS BELIEVING

SEEING IS BELIEVING

Janin

was completely taken in by what he saw. In his report to Ralston, he

estimated that a work crew of 20 men could mine $1 million worth of gems

a month. He collected a $2,500 fee for his efforts, plus an option to

buy 1,000 shares in the planned mining company for $10 a share. He used

the $2,500 and somehow came up with another $7,500 to buy all 1,000

shares; then he staked a mining claim on 3,000 acres of surrounding

land, just in case it had precious stones, too.

One of the

secrets of pulling off a scam is knowing when to get out. It was at this

point that Arnold and Slack decided to make their exit. Slack had

already cashed out for $100,000; Arnold now sold his stake for a

reported $550,000, and both men skipped town.

EMPIRE BUILDER

As

Arnold and Slack made their getaway, William Ralston was hard at work

putting together a $10 million corporation called the San Francisco and

New York Mining and Commercial Company. He’d already lined up 25 initial

investors who contributed $80,000 apiece, and now he was preparing to

raise another $8 million. New York newspaper publisher Horace Greeley

had already bought into the company; so had British financier Baron

Ferdinand Rothschild.

A Rothschild investing in a

diamond field? The house of Rothschild was a world-renowned banking firm

and experienced at spotting good investments. With Tiffany and

Rothschild involved, the excitement surrounding the diamond field grew

to a fever pitch. No one but Arnold and Slack knew where the mine was,

but so what? When rumors began spreading that it was somewhere in

Arizona Territory, fortune seekers by the hundreds began making their

way there in hopes of finding strikes of their own.

LOCATION, LOCATION, LOCATION

The

stage was now set for the swindle to grow much bigger, which meant that

a lot more people would have lost a lot more money. That it didn’t

happen was due purely to chance: when Arnold and Slack picked the

location of the “diamond field,” they unknowing chose an area where a

team of government geologists had been conducting surveys for five

years.

The leader of the geological team was a man named Clarence

King. When he learned of the diamond strike, he couldn’t believe what

he was hearing. He’d been all over the territory and had already filed a

report stating that there were no deposits of precious gems of any kind

anywhere in the area. If the story were true, he and his team of

experts had missed a significant diamond field that two untrained miners

had been able to find on their own. His professional reputation was on

the line: If there really was a diamond field and word of it got back to

Washington, D.C. he would be exposed as incompetent and funds for the

survey would be cut off.

TOO GOOD TO BE TRUE?

King

arranged to meet the engineer Henry Janin over dinner to get a

firsthand account of the diamond field story. As he listened to Janin

describe his trip to the site, he started to smell a rat. Janin reported

finding diamonds, rubies, and sapphires next to each other, and as a

geologist, King knew that was impossible. The natural process by which

diamonds are created are so different from those that create rubies and

sapphires that they are never founding the same deposits.

Because

Janin had been blindfolded on the trip to the site, he couldn’t tell

King where it was. But King was so familiar with the area that after

quizzing Janin, he was able to figure out which mesa he was talking

about. The next day he and some members of his team set out to visit the

site themselves.

ON THE SPOT

They

arrived at the site a few days later. It was fairly late in the day, so

they set up camp and then started exploring the area. As had been

Janin’s experience, it didn’t take long for them to find raw diamonds,

rubies, and other gems. By the time King was ready to turn in for the

night, he’d found so many precious stones that even he had a

touch of diamond fever. He went to bed wondering if the field was really

genuine, and maybe even hoping a little that it was. That hope vanished

early the next morning.

* Shortly after sunrise, another member

of the party found a diamond that was partially cut and polished.

Nature is capable of many things, but it takes a jeweler to cut and

polish a diamond- the stone had been planted there by human hands.

*

King noticed that wherever he found diamonds, he found other precious

stones in the same place, and always in roughly the same quantities,

something that does not happen in nature.

* Upon close

examination, the team also noticed that the crevices in which the gems

were found had fresh scratch marks, as if the gems had been shoved into

place with tools.

* When precious stones were found in the earth,

it was always in places that had been disturbed by foot traffic. When

they went to areas that were undisturbed, they never found anything.

DIGGING DEEP

King

knew that if the field was real, diamonds would also be found in the

ground as well as on the surface. As a final test, he and his men went

to an undisturbed area where they thought diamonds might occur naturally

and dug a trench ten feet deep. Then they carefully sifted through all

of the dirt that had been removed from the trench, and found not a

single precious stone in any of it. There was no question about it: the

find was a hoax. Arnold and Slack had planted the gems.

As soon

as King got to a telegraph station, he sent word to Ralston in San

Francisco that he’ been conned. Ralston was shocked and angry. He closed

the company and returned the unspent capital to the original 25

investors. Then, because his reputation was on the line, he refunded the

rest of their investment out of his own pocket, which cost him about

$250,000. It turns out that Ralston’s bad judgment wasn’t limited to

diamonds: He poured millions into the building of San Francisco’s Palace

Hotel and other money-losing schemes, which contributed to the Bank of

California’s collapse in 1875. His body was found floating in the San

Francisco Bay the following day, though the cause of death remains a

mystery.

THE HOAX EXPOSED

THE HOAX EXPOSED

The

Great Diamond Hoax of 1872, as it came to be known, received widespread

newspaper coverage not just in America but also in Europe. As reporters

in the United States and abroad researched the story, details of how

the hoax had been perpetrated began to emerge.

* Arnold had once

been a bookkeeper for the Diamond Drill Company of San Francisco, which

used industrial-grade diamonds in the manufacture of drill bits. He

apparently stole his first batch of not-so-precious gems from work, then

bought cheap, uncut rubies and sapphires from other sources and added

them to the mix. None of the people he duped had been able to tell

industrial-grade diamonds and second-rate gems from the real thing.

*

When Ralston and the other early investors paid Slack the first

installment of $50,000 for his share of the mine, he and Arnold made the

first of two trips to London, where they bought $28,000 worth of

additional uncut stones from diamond dealers there. Most of the gems

were used to salt the claim in Colorado; the few that were left over

were the ones Tiffany and his assistant had foolishly valued at

$150,000.

AFTERMATH

Philip

Arnold and John Slack made off with $650,000, which in 1872 should have

set them up for life. Neither of them fared very well, though. Arnold

moved to Kentucky and bought a 500-acre farm. When the law eventually

tracked him down, he paid a reported $150,000 to settle the claims

against him, then used the remaining money to start his own bank. Six

years after the diamond hoax, he was injured in a shootout with another

banker; he died from pneumonia six months later at the age of 49.

Less

is known about Slack. He apparently blew through his share of the loot

and had to go back to work, first as a coffin maker in Missouri and then

as a funeral director in New Mexico. When he died there in 1896 at the

age of 76, he left an estate valued at only $1,600.

Uncovering

and exposing the fraud gave Clarence King’s career a huge boost; in 1879

he became the first director of the U.S. Geological Survey. But he was a

better geologist than he was a businessman, as he learned to his dismay

in 1881 when he quit working for the government and took up ranching.

He failed at that, then went on to fail at mining and banking. He died

penniless in 1901 at the age of 59.

FOOL’S GOLD

So

did anyone come out ahead from the experience? Apparently only Henry

Janin, the mining engineer who’d vouched for the authenticity of the

diamond field. He suffered a blow to his reputation when the hoax was

exposed, but by then he’d already sold his $10,000 worth of shares to

another investor for $40,000. Janin was never implicated in the scam; as

far as anyone knows, his good fortune was just a case of dumb luck.

The

next morning the two men went to the Bank of California and deposited

their bag in the bank’s vault. They made another big show of not wanting

anyone to know what was in the bag, and again they let some of the bank

employees have a peek. Soon everyone in the bank knew what was in it,

including the president and founder, William Ralston. He had made a

fortune off the Comstock Lode, and had his eye out for the next big

find. Ralston didn’t keep the men’s secret, and neither did George

Roberts: Soon all of San Francisco, the city built by the Gold Rush of

1849, was buzzing with the tale of the two miners and their discovery.

The

next morning the two men went to the Bank of California and deposited

their bag in the bank’s vault. They made another big show of not wanting

anyone to know what was in the bag, and again they let some of the bank

employees have a peek. Soon everyone in the bank knew what was in it,

including the president and founder, William Ralston. He had made a

fortune off the Comstock Lode, and had his eye out for the next big

find. Ralston didn’t keep the men’s secret, and neither did George

Roberts: Soon all of San Francisco, the city built by the Gold Rush of

1849, was buzzing with the tale of the two miners and their discovery.