by Edgar B. Herwick III

Samoset speaks English to the British colonist

By the 1830s, almost all of the large hardwood trees in Massachusetts had been cut down.

Jesse "Little Doe" Baird, vice chair of the Mashpee Wampanoag tribe explains that this was a huge problem for the growing state.

“The

local economies depended on cash and needed a product to bring in that

cash. And that product - at the time - was fuel and the fuel was wood.”

One of the few places in the state that still had virgin hard wood was the land set aside for the Mashpee Indians.

The

tribe generally did not have a cash economy so it’s not like they were

trying to cut wood produce wood and sell wood for cash, they made a

living off the land itself.

For years, white men had been

encroaching on the Mashpee’s land, cutting – and taking their wood. And

for years, the Mashpee had been writing to Massachusetts officials about

this – and a host of other issues - usually in their native language.

"One

of the problems obviously is that generally people are not going to be

able to read or understand that language," Baird said. "But even if they

could you have a group of people asking the group people that are

responsible for their condition to fix their condition."

And so,

the Mashpee decided it was time to fix it themselves. Enter William

Apess, a Pequot Indian – and an ordained Methodist minister. He’d heard

about the struggles in Mashpee and had a notion that he could help.

"He

had a different approach in terms of how to speak to the white man of

the day," Mashpee Wampanoag tribal historic preservation officer Romana

Peters said.

Peters pointed out that Apess had the ear of white

men and high places, and had the political acumen to present the

Mashpee’s case in terms that officials couldn’t ignore.

"Things

like we shared a desire for liberty, we fought together during the

Revolutionary war both wanting liberty and freedom and that’s no less

than Mashpee Indians are asking for now," Peters said.

And so a

tribal council was convened on May 21, 1833. Apes and the Mashpee

leaders drew up a document that has come to be known by some as the

Mashpee Indian Declaration of Independence. Not only did the Mashpee

declare the right to govern themselves, they also drew a line in the

sand. As of July 1, outsiders would no longer be permitted to cut wood

on their land.

Predictably, when July 1 came, so did the white

men. Despite the warnings, two men from Barnstable piled up their horse

drawn cart with freshly cut virgin hard wood. That’s when they were met

by six Mashpee – including Apess – who proved to be as good as their

word.

"The cart was dumped over, they said, ‘You’re not going to

take the wood,' and so the wood was dumped out and the men left with

their cart."

As a result, the six Mashpee men were arrested. But

the “wood riot” - as it came to be known – proved to be a turning

point. It garnered much attention in the press and finally opened up a

dialogue with Massachusetts’ officials that eventually earned the

Mashpee an unprecedented level of control over their own land - and

governance.

"It definitely was a huge step in the right

direction for people to be able to practice self-determination and not

be under a different set of laws simply because of the color of their

skin and their different life-style," Peters said.

Peters points out, it’s a path of self-determination that the Mashpee - and other tribes – are still carving out - even today.

"Each

President issues a new policy on how to treat American Indians.

Sometimes it’s been assimilation; sometimes it’s been extermination.

Right now, since the Clinton administration, tribes across the country

have been deemed sovereign nations, so you see the evolution of this and

people being more ready to be sovereign once again."

The Mashpee Declaration of Independence, drafted and signed 181 years ago this week.

by Eddie Deezen.

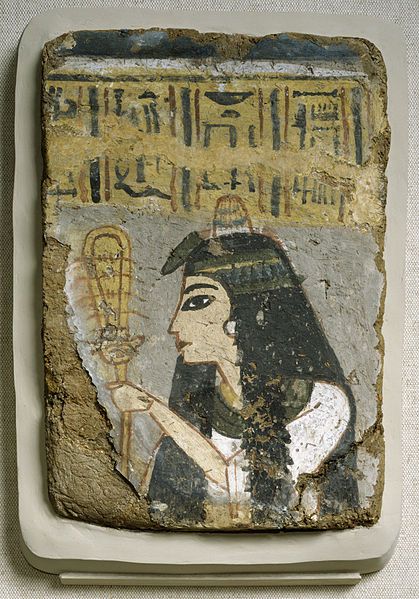

by Eddie Deezen. But

unlike today's modern women, they weren't trying to impress that cute

guy at work or the guy at that important job interview. And the Egyptian

women weren't trying to catch the eye of the burly construction foreman

working on the pyramids or the local pharoah either. Their sights were

aimed a little higher. They were trying to impress the gods.

But

unlike today's modern women, they weren't trying to impress that cute

guy at work or the guy at that important job interview. And the Egyptian

women weren't trying to catch the eye of the burly construction foreman

working on the pyramids or the local pharoah either. Their sights were

aimed a little higher. They were trying to impress the gods.