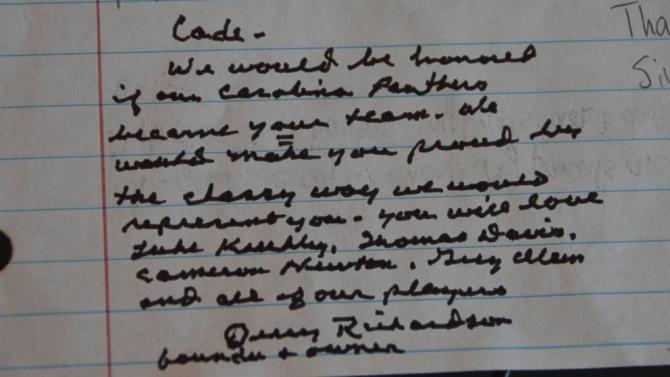

A specimen of the new scorpion

species Eramoscorpius brucensis, which lived about 430 million years

ago, making it among the earliest scorpions.

The species probably lived

in water, but it had feet that would have allowed it to scuttle about on

A new scorpion species found fossilized in the rocks of a

backyard could turn the scientific understanding of these stinging

creatures on its head.

The fossils suggest that ancient scorpions crawled

out of the seas and onto land earlier than thought, according to the

researchers who analyzed them. In fact, some of the oldest scorpions had

the equipment needed to walk out of their watery habitats

and onto land, the researchers said. The fossils date back some 430

million to 433 million years, which makes them only slightly younger

than the oldest known scorpions, which lived between 433 million and 438

million years ago.

The new species "is really important, because

the combination of its features don't appear in any other known

scorpion," said study leader Janet Waddington, an assistant curator of

paleontology at the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto.

Backyard fossils

The new species fell into Waddington's hands almost by happenstance.

Museum curators frequently get calls about fossils, most of which are

run-of-the-mill, she told Live Science. But a woman who called about an

"insect" in her backyard stone wall had something very exciting on her

hands.

"When she showed me this fossil, I just about fell on the floor, it was so amazing," Waddington said.

The fossil was no insect, but rather a scorpion

— and a new species at that. Over the years, more specimens trickled

in, mostly from patio stones and rock quarries, and one from a

mislabeled fossil at a national park on Canada's Bruce Peninsula. Now,

Waddington and her team have 11 examples of the new species, ranging in

length from 1.1 inches (29 millimeters) to 6.5 inches (165 millimeters).

What made the animal, dubbed

Eramoscorpius brucensis, so fascinating was its legs.

Walking in water

Previously, the earliest scorpion fossils found came from rocks that

were originally deposited in the water, leading paleontologists to

believe that the animals evolved on the seafloor, like crabs, and only

later became landlubbers. Ancient scorpions had legs like crabs, with a

tarsus, or foot segment, that was longer than the segment preceding it.

This arrangement, Waddington said, would have meant the creatures walked

on their "tippy-toes," such as crabs do today.

But

E. brucensis

was different. This species had a tarsus segment that was shorter than

the segment before it, which would have made it possible for the animal

to set its tarsus flat against the ground. In other words, this scorpion

had feet.

"They could have walked on their feet, which is really

important because it meant that they could have supported their own

weight," Waddington said. Without the need for water to buoy them up,

the animals could have walked on land.

The fossils also show that the scorpions' legs were solidly attached at

the body, without the exaggerated "hinge" seen in scorpions that would

have needed water to stay upright. What's weird, Waddington said, is

that all the other features of these scorpions seem aquatic. They are

found in marine rocks, and their digestive systems appear to require

water (in today's land scorpions, digestion begins outside of their

bodies, a process that requires adaptations these ancient scorpions lack).

Waddington said she and her team suspect that the fossils they've

collected are not the bodies of dead scorpions at all. Instead, they may

be molts, exoskeletons left behind as the scorpions grow. Scorpions are

incredibly vulnerable during molting, Waddington said, and in deep

water, ancient squidlike animals would have loved a helpless scorpion

snack. The scorpions that could haul themselves out of the water onto

the shore to escape predators would have had a survival advantage. The

rocks that house the scorpion fossils often feature ripples that would

have been created when wind blew thin films of water over land,

suggesting a shoreline lagoon habitat.

What that means is that the first adaptations that scorpions developed

for life on land could have appeared much earlier than researchers

thought.

"Our guys are really, really old," Waddington said. "They're vying for the second-oldest [scorpions] known."

The researchers reported their findings today (Jan. 13) in the journal Biology Letters.