by Kira Lerner

In 2013, Kelli Jo Griffin took her four young

children with her when she went to vote in the municipal election in her

town of Montrose, Iowa. Her oldest daughter had just learned about

elections and voting in school and Griffin thought the outing would be a

good experience for them to experience democracy in action.

But a few weeks later, Griffin received a call from a state Division

of Criminal Investigation officer who was sitting in a car outside her

house, asking her to verify the signature on the ballot. “He assured me I

was not in trouble but he was just in the area doing some signature

verification,” Griffin said. Confused, she contacted her local police

station after the officer had left — that part of voting was not

included in the elementary school democracy lesson.

Griffin later learned that the county attorney had decided to

press charges

for perjury. Suddenly, she was facing time in prison for attempting to

cast a ballot as a former convicted felon. Griffin had served a period

of probation almost five years earlier for delivering a small amount of

cocaine, a low-level drug offense, and was unaware that her voting

rights had been permanently revoked.

“My fear was that I was going to be taken away from my children,”

Griffin told ThinkProgress. “And who was going to watch them if that

happened?”

If Griffin had attempted to vote before January 2011, she would have

been in the clear. On that day — the first of his term — newly elected

Republican Gov. Terry Branstad

issued an executive order

reversing former Gov. Tom Vilsack (D)’s 2005 order which had restored

the right to vote to felons who had been disqualified in the state, a

total of 110,000 people at the time. Branstad’s order made Iowa one of

the

most difficult states in the nation for felons to vote.

Griffin was one of 68 former felons who were investigated by

then-Secretary of State Matt Schultz (R) for voting despite the

revocation of their rights. Schultz claimed the state had a massive

voter fraud problem but uncovered an

infinitesimal number of cases of potential fraud.

Griffin was ultimately acquitted of voter fraud by a jury. But even

though she avoided jail time, she still can’t vote for the rest of her

life. Now she’s the lead plaintiff in the

Iowa ACLU’s lawsuit

challenging Iowa’s practice of felon disenfranchisement. The suit

claims that citizens convicted of most felonies are not guilty of an

“infamous crime”

— an “egregious” or “heinous” crime, according to the state

constitution, which could challenge the integrity of an election like

bribery or corruption — so they should have their voting rights restored

automatically after their sentence is up. Under Iowa law, those who

commit infamous crimes have their voting rights revoked for life.

Last year, the

Iowa Supreme Court reinstated

voting rights to Iowans who had been convicted of aggravated

misdemeanor — the court found that this type of crime could never be

infamous — and

left the door open for another lawsuit to challenge the law regarding felonies.

“Our lawsuit argues that Kelli’s type of conviction, which is for a

nonviolent drug offense, the lowest level of felony, can’t by definition

be infamous,” ACLU attorney Rita Bettis told ThinkProgress. “It doesn’t

implicate the integrity of elections and there’s no element of deceit

in having a substance abuse issue.”

If the case is successful, everyone who has been convicted of the

same category of crimes as Griffin will also have their voting rights

restored. It’s difficult to put a number on the people who could be

affected because the court could draw the line in a number of places,

Bettis said. The court could grant voting rights to only nonviolent

offenders, or it could extend rights to as many as 14,000 people — the

total number of Iowans who have had their sentences discharged since

Gov. Branstad’s 2011 order. The ACLU argues a very small number of those

14,000 committed what it defines as infamous crimes.

And an equally

small number have already attempted to reinstate their rights by applying to the governor. The

AP found in 2012

that less than a dozen Iowans had successfully made it through the

process of restoring their rights with the governor. In 2013, the

governor restored rights to

21 Iowans out of the thousands being discharged from prison or parole.

“I hope that not only me but thousands of people who have already

fulfilled their conviction to the court system are able to vote,”

Griffin said.

“I hope [the lawsuit] also educates people about voting,” she added.

“There are so many people who have the right to vote and choose not to. A

lot of them now are coming to me now and saying I don’t want to vote

because I don’t know if I can. Me doing this lawsuit is going to

hopefully help people know, yes you can vote.”

Even though Griffin escaped the state’s charges against her and is no

longer facing the prospect of prison time, she is still barred from

voting — a concept she said many of the jurors in her case did not

understand. “If people who sat through my trial were still confused

about the voting laws afterwards, what do people who didn’t have any

kind of education on it think?” she said.

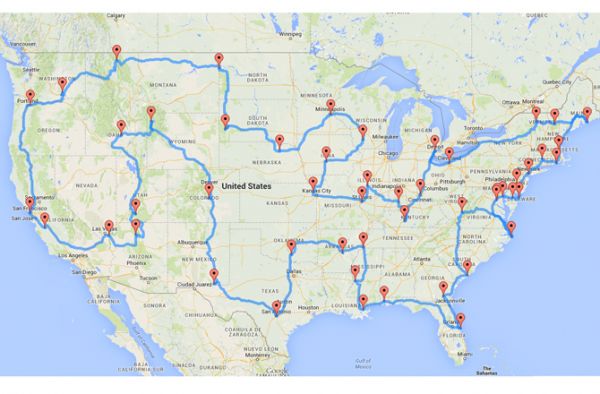

Iowa is one of three U.S. states that permanently disenfranchise

people convicted of felonies. Iowa, Kentucky, and Florida require felons

to apply to the governor to have their voting rights restored. On the

other side of the spectrum, only two states — Vermont and Maine — grant

full voting rights to prisoners. More than 30 states prohibit people on

probation and parole from voting.

Iowa’s recent moves under Gov. Branstad are a step backward compared

to most of the country, which is shifting toward expanded voting rights

for formerly incarcerated Americans.

According to the National Conference of State Legislatures,

28 states passed new laws expanding felon voting rights between 1996

and 2008. During that time, seven states repealed lifetime

disenfranchisement laws, at least for some ex-offenders, and 12 states

simplified the process for regaining voting rights by making changes

like eliminating a waiting period or streamlining the paperwork process.

Virginia is one of the most recent states to

address its felon disenfranchisement problem.

Both former Gov. Bob McDonnell (R) and current Gov. Terry McAuliffe (D)

made significant changes to the rights restoration process. In May

2013, McDonnell granted “automatic restoration” to people convicted of

nonviolent felonies and last April, McAuliffe reduced the mandatory

waiting period for offenders with violent offenses to apply for rights

restoration from five years to three years and

removed drug offenses from the violent crime categorization. Still, the process isn’t easy, and Virginia is currently tied with Kentucky for the

second-highest

number of disenfranchised citizens in the country, at 450,000. The

General Assembly has repeatedly rejected proposals to amend the

constitution to allow for automatic restoration and last year the

Republican-controlled House eliminated proposed funding for rights

restoration work.

In Florida, the state which disenfranchises the most U.S. citizens, voting rights groups are pushing for a

constitutional amendment on the ballot in 2016, which would allow automatic restoration for state residents who complete their sentences.

Many states still have significant progress to make — in the 2008

election, 5.3 million Americans, or one in 40 adults, were unable to

vote due to a felony conviction,

according to the Sentencing Project. Nationally,

2.2 million

— or one in every 13 — black adults is disenfranchised, and black

adults are four times more likely to lose their voting rights than the

rest of the adult population.

Before Iowa Gov. Vilsack’s 2005 executive order, one in four African

American men of voting age was permanently disenfranchised in the state.

And until recently, Iowa had the highest percentage of African American

citizens incarcerated —

Wisconsin recently overtook it in the “shame category,” Bettis said.