Anyone can toilet paper a house or slip a whoopee

cushion onto a chair. Pulling off a truly legendary prank is harder. To

fool the media, crowds, and even the military, you need patience,

planning, and more than a little genius. But when everything comes

together into one big victimless laugh, it’s a thing of beauty. Here

are history’s greatest hoaxes, each one proof that with effort and a

little luck, you can fool a lot of the people, all of the time.

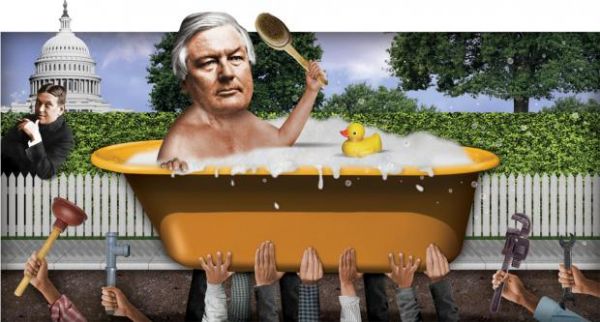

1. The Birth of the Bathtub!

December

20 gets no respect. On the calendar, it’s just another winter day best

known for not being Christmas. But in 1917, writer H. L. Mencken set

out to change that. When readers of the

New York Evening Mail

opened the paper in late December, they found Mencken’s 1,800-word

essay “A Neglected Anniversary,” detailing the arrival of the bathtub in

the United States. Mencken meticulously cataloged the tub’s rocky

debut in 1842, explaining how the bathroom fad had caught on only after

Millard Fillmore installed one in the White House. By the 20th

century, Mencken explained, the momentous anniversary had fallen into

obscurity. “Not a plumber fired a salute,” he lamented. “Not a governor

proclaimed a prayer.”

There’s a good reason why. Mencken had

made the whole thing up. The humorist figured everyone would see

through the ruse, and he later wrote that the article was “harmless

fun” meant to distract readers from World War I. “It never occurred to

me it would be taken seriously,” he wrote.

But printing the piece in the

Evening Mail

gave Mencken’s little joke extra credibility, and he was stunned by

how the story snowballed. Within a few years, it had been referenced in

“learned journals” and cited “on the floor of Congress.” The tale

became so pervasive that the

Boston Herald ran an article in

1926 debunking it under the headline "The American Public Will Swallow

Anything." Three weeks later, the same paper cited Mencken’s bathtub

origin tale as fact.

Mencken tried to set the record straight, but

his efforts were futile. People were more interested in hearing about

President Fillmore’s tub than hearing the truth. Even today, the nugget

resurfaces from time to time: In 2008, the story was featured in a Kia

ad, which hailed Fillmore as “best remembered as the first president

to have a running water bathtub.” Poor guy can’t even be remembered for

something he actually did.

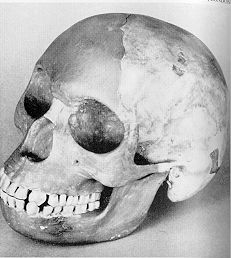

2. Sherlock Holmes Finds the Missing Link

Ever since Darwin published

On the Origin of Species,

scientists have been looking for the missing link—a transitional

fossil that would seal the argument for human evolution. In 1912, an

amateur geologist and archaeologist named Charles Dawson found it. The

skull he pulled from a gravel pit in Piltdown, England, seemed to

conclusively fit the part, and the discovery rocked the scientific

community. Skeptics claimed the fossil was exactly what it looked like:

a human skull cobbled together with an ape jaw to fool gullible

scientists. In the ensuing excitement, believers shouted down deniers,

and in December 1912, the Geological Society of London hosted a

ceremony where Dawson presented his fossil, the Piltdown Man.

The

doubters continued doubting until 1917, when researchers discovered a

similar fossil nearby. The Piltdown faithful were thrilled: the new

find, Piltdown II, seemingly legitimized the old one.

But

the Piltdown Man’s scientific legitimacy gradually eroded over the

next few decades. Other early human skulls began popping up in China

and Africa, and each had an apelike skull with a human jaw: the

opposite of the Piltdown combo.

The jig was finally up in 1953.

After conducting tests on the skull, anthropologist Joseph Weiner and

geologist Kenneth Oakley determined Piltdown Man was no man at all.

Rather, he was a combination of man (the skull), orangutan (the jaw),

and chimp (the teeth). What’s more, fluorine dating showed that the

bones were no more than 100,000 years old, certainly not new but not

missing-link ancient. The head looked older only because the hoax’s

perpetrator had stained it with iron and chromic acid.

While the

hoax was eventually exposed, the prankster behind the caper is still at

large. Dawson is the most likely culprit, but literary sleuths have

turned their suspicions to another man: Sherlock Holmes’s creator, Sir

Arthur Conan Doyle. Not only was Conan Doyle a member of Dawson’s

archaeological society and a frequent visitor to the Piltdown site, he

hinted in his novel

The Lost World that faking bones is no tougher than forging a photograph—the ultimate smoking gun! If only Holmes were on the case.

3. Italy’s Secret Pasta Gardens

Where does spaghetti come from? On April 1, 1957, the BBC news program

Panorama

tackled the question with a segment about a Swiss town’s robust

spaghetti crop, brought on by a warm spring and the disappearance of the

spaghetti weevil. “For those who love this dish, there’s nothing like

real homegrown spaghetti,” anchor Richard Dimbleby said.

Viewers

ate it up. On April 2 the BBC was flooded with hundreds of phone calls

from people eager to grow their own noodles, then a rare treat for

British diners. Keeping the whimsy going, the BBC instructed anyone

interested in a pasta-bearing tree to “Place a sprig of spaghetti in a

tin of tomato sauce and hope for the best.”

4. The World’s Worst Bestseller

Everyone

knows you can’t judge a book by its cover. But the aphorism got an

extra dose of validity in 1969, when Penelope Ashe, a bored Long Island

housewife, wrote the trashy sensation

Naked Came the Stranger.

As

part of her book tour, Ashe appeared on talk shows and made the

bookstore rounds. But Ashe wasn’t what her book jacket claimed. The

author was as fictional as the novel she supposedly wrote—and both were

the work of Mike McGrady, a Newsday columnist disgusted with the lurid

state of the modern bestseller. Instead of complaining, he decided to

expose the problem by writing a book of zero redeeming social value and

even less literary merit. He enlisted the help of 24

Newsday

colleagues, tasking each with a chapter, and instructed them that there

should be “an unremitting emphasis on sex.” He also warned that “true

excellence in writing will be quickly blue-penciled into oblivion.” Once

McGrady had the smutty chapters in hand (which included acrobatic

trysts in tollbooths, encounters with progressive rabbis, and cameos by

Shetland ponies), he painstakingly edited the prose to make it worse.

In 1969, an independent publisher released the first edition of

Naked Came the Stranger, with the part of Penelope Ashe played by McGrady’s sister-in-law.

To

the journalist’s dismay, his cynical ploy worked. The media was all

too fascinated with the salacious daydreams of a “demure housewife”

author. And though

The New York Times wrote, “In the category

of erotic fantasy, this one rates about a C,” the public didn’t mind. By

the time McGrady revealed his hoax a few months later, the novel had

already moved 20,000 copies. Far from sinking the book’s prospects, the

press pushed sales even higher. By the end of the year, there were more

than 100,000 copies in print, and the novel had spent 13 weeks on the

Times’s

bestseller list. As of 2012, the tome had sold nearly 400,000 copies,

mostly to readers who were in on the joke. But in 1990, McGrady told

Newsday he couldn’t stop thinking about those first sales: “What has

always worried me are the 20,000 people who bought it before the hoax

was exposed.”

5. Bipedal Beavers, Unicorns, and Other Moon Monsters

Much

like submarines, submarine sandwiches, and the U.S. Constitution, the

ethics of journalism were still evolving in the early 19th century. One

rule that hadn’t totally sunk in yet: Don’t ply your readers with

outright fabrications. The newspapers of the day routinely manufactured

stories to generate sales, but none was as outrageous as the New York

City rag

The Sun’s “Great Moon Hoax,” a series of six articles published in 1835 about the discovery of civilization on the moon.

The

articles claimed that a British astronomer named John Herschel had

used a powerful new telescope to spot plants, unicorns, bipedal

beavers, and winged humans there. The articles even went a step further,

claiming that our angelic moon brethren collected fruit, built temples

from sapphire, and lived in total harmony. The hoax was debunked

immediately. Soon after the first installment ran in

The Sun, its uptown competition, the

New York Herald, slammed the story under the headline "The Astronomical Hoax Explained."

But

the American public preferred a universe dotted with angels, unicorns,

and bedazzled architecture. The story created such a buzz that papers

around the world rushed to reprint it, while a theater company in New

York worked out a dramatic staging. Before long,

The Sun was

making extra coin selling pamphlets of the whole series and

lithographic prints that depicted life on the moon. It took five years

for the story’s writer, Richard Adams Locke, to finally confess to

making it all up. As he wrote in the

New World, his intention

was to satirize “theological and devotional encroachments upon the

legitimate province of science.” But in all this, the thing we can’t

believe is that no New York team has embraced the moon beaver as its

mascot.

6. A Math Whiz Horse!

Is

a hoax still a hoax if the perpetrator doesn’t know it? Wilhelm von

Osten would likely say no. At the turn of the 20th century, the German

math teacher was determined to prove the intelligence of animals. After

trying (and failing) to teach a cat and a bear how to add, he finally

found a sufficiently studious beast. With years of training, a horse

named Hans could add, subtract, multiply, and read German.

Von

Osten held regular displays of his star pupil’s intelligence. Hans

would calculate sums and convert fractions by tapping a hoof to

indicate numbers. He became a national sensation, made headlines in the

United States, and earned the nickname Clever Hans. To prove that the

horse’s skills were real, Von Osten allowed a group of experts to

examine his equine genius. They found nothing fishy, and Germany

embraced Hans as a marvel until psychology student Oskar Pfungst came

along.

Unsatisfied with the work of the experts, Pfungst examined

Hans and figured out how the horse was doing its calculator act. Von

Osten was sending him subconscious signals. Each time Hans was

presented with a math question, he’d tap away until a subtle cue on his

owner’s face told him to stop. The cues were so subtle that Von Osten

didn’t even know he was giving them. Indeed, the horse got problems

right only when they were simple enough for Von Osten to solve, and his

percentages plummeted when he wasn’t allowed to face his master. When

Pfungst exposed the truth, Von Osten denied it, insisting that Hans

really was clever, and he continued to parade his horse before happy

crowds. Today, animal psychologists know to write off these cues as the

“Clever Hans effect.”

7. The Supergroup That Never Got To Rock

Music fans got exciting news in 1969 when

Rolling Stone

reviewed the first album by the Masked Marauders, a supergroup

featuring Bob Dylan, Mick Jagger, John Lennon, and Paul McCartney. Due

to legal issues with their respective labels, the stars’ names wouldn’t

appear on the album cover, but the review extolled the virtues of

Dylan’s new “deep bass voice” and the record’s 18-minute cover songs.

One of the album’s highlights was an extended jam between bass guitar

and piano, with Paul McCartney playing both parts! The writer earnestly

concluded, “It can truly be said that this album is more than a way of

life; it is life.” For anyone paying attention, the absurd details

added up to a clear hoax. The man behind the gag, editor Greil Marcus,

was fed up with the supergroup trend and figured that if he peppered

his piece with enough fabrication, readers would pick up on the joke.

They

didn’t. After reading the review, fans were desperate to get their

hands on the Masked Marauders album. Rather than fess up, Marcus dug in

his heels and took his prank to the next level. He recruited an

obscure San Francisco band to record a spoof album, then scored a

distribution deal with Warner Bros. After a little radio promotion, the

Masked Marauders’ self-titled debut sold 100,000 copies. For its part,

Warner Bros. decided to let fans in on the joke after they bought the

album. Each sleeve included the

Rolling Stone review along with

liner notes that read, “In a world of sham, the Masked Marauders,

bless their hearts, are the genuine article.”

8. How April Fools’ Day Didn’t Get Its Name

As

Joseph Boskin would tell you, the origins of April Fools’ are murky.

In fact, the Boston University professor and pop culture historian was

trying to say just that in a 1983 interview with reporter Fred

Bayles. But each time Boskin told Bayles that no one is quite sure how

the holiday started, the interviewer pushed him for a more concrete

answer. Eventually, the academic got fed up with the aggressive

questioning and decided to concoct a story worth printing.

Off

the top of his head, Boskin began regaling Bayles with a tale from the

days when Constantine ruled Rome. Jesters, he said, petitioned the

emperor to allow one of their own the chance to rule for just one day.

On April 1, Constantine relented. A jester, King Kugel—Boskin named

him for the Jewish pudding dish—took over and proclaimed that April 1

would always serve as 24 hours of silliness.

Boskin later said he

made the story so absurd that Bayles would have to catch on. No dice.

The AP ran Bayles’s story about King Kugel, and soon Boskin was

fielding calls from news outlets across the country. He initially kept

up the ruse, but a few weeks later, the truth slipped out during one

of his lectures about the media’s willingness to believe rumors. The

editor of the school paper was in the class, and the campus

Daily Free Press ran a headline declaring “Professor Fools AP.”

Once

the truth was out, the AP was predictably embarrassed, but the story

has a happy ending. Bayles, no longer an eager reporter, is now a

professor of journalism at BU, where he can speak from personal

experience about the media’s gullibility.

9. Virginia Woolf Ships Out

Before

Virginia Woolf and E. M. Forster were literary titans and before John

Maynard Keynes was the father of modern economics, they were part of a

crowd of friends that informally called themselves the Bloomsbury

Group. Comprising writers, artists, and thinkers, the group basically

functioned as a fraternity for geniuses. So it’s fitting that the

group’s lasting legacy is a piece of tomfoolery.

In 1910, the

HMS Dreadnought

was the fiercest, strongest ship in the Royal Navy. To the poet

William Horace de Vere Cole, it seemed like the perfect place for the

Bloomsbury Group to stage a high-concept prank. Cole, Woolf, her

brother Adrian Stephen, and three pals decided to sneak aboard the

Dreadnought,

disguised as the emperor of Abyssinia and his entourage. Why risk the

wrath of the Royal Navy? Because it was funny! The group sent a phony

telegram to the ship’s commander, letting him know that a delegation

was en route, then they simply showed up at the ship.

Amazingly,

it worked. Dressed in caftans, turbans, and gold chains and with their

faces painted black, the “Abyssinians” were welcomed aboard the

Dreadnought

with an honor guard, a red carpet, and a naval band. Despite the

intentionally amateurish costumes, including at least one mustache

that began falling off in the rain, the Abyssinians stayed in character

for the entire tour. When they spoke, it was either to exclaim “Bunga,

bunga!” in excitement or ramble in an invented language of Latin,

Swahili, and gobbledygook. At one point, they were forced to decline a

meal, relaying through Stephen, who was acting as translator, that the

food had not been prepared to their specifications. In reality, they

didn’t eat because they were afraid their makeup would come off.

The

tour ended without the crew suspecting a thing. But then someone

called reporters. British papers had a field day with the story. Sailors

were heckled with cries of “Bunga, bunga” in the streets, and King

Edward himself made his displeasure with the incident known. In the face

of such humiliation, the navy was forced to take action. According to

contemporary accounts, the navy got its revenge by caning two of the

male hoaxers. Woolf was spared the lash because she was a woman, even

though a lady’s mere presence on the ship was one of the greatest

sources of the navy’s embarrassment.

Eventually, though, the Royal Navy developed a sense of humor about the incident. When the

Dreadnought

rammed and sank a German submarine during World War I, its crew

received a congratulatory telegram from superiors. The text? “BUNGA

BUNGA.”

10. A Bordello of Barks

Joey

Skaggs is a professional prankster who plays the media like his

instrument. He’s made waves posing as an outraged gypsy hell-bent on

renaming the gypsy moth. He launched Walk Right!—a fictional group

dedicated to enforcing proper walking etiquette through militant

tactics. But perhaps the best illustration of his life’s work is the

brothel for dogs that he opened in 1976. The prank started when Skaggs

ran an ad in

The Village Voice offering dog owners a chance to

buy their pets a night with alluring companions, including Fifi, the

French poodle. To Skaggs’s surprise, he began getting calls from people

wanting to drop $50 for his service.

It didn’t take much for the

media to bite, and when reporters showed up with questions, Skaggs

reeled them in by staging a night at his “cathouse for dogs.” The stunt

worked; TV stations issued breathless reports of the wanton acts of

canine carnality. The ASPCA launched an investigation, a veterinarian

publicly condemned the brothel, and the New York Health Department

raised concerns about Skaggs’s licensing.

Skaggs eventually

admitted the whole thing was a goof, but not everyone believed him. To

this day, a television producer for WABC New York argues that the

brothel was real and that Skaggs’s hoax claims are just a clumsy

attempt to cover his trail. Of course, WABC has good reason to insist

that Skaggs was running a genuine poodle prostitution ring: The station

won an Emmy for its coverage of the story.

11. MIT Blows Up Harvard!

MIT

students derive great pleasure from tormenting their rivals at

Harvard. Our favorite prank of theirs occurred during the 1982

Harvard-Yale football game when a weather balloon emblazoned with the

letters “MIT” began emerging from the ground near the 50-yard line. In

the preceding days, a group of MIT students had snuck into Harvard

Stadium and wired a vacuum motor to blow air into the balloon until it

exploded, proving once again why you don’t mess with engineers.

12. Greasing the Wheels

Back

in the late 19th century, college teams took trains to get to road

games, and Auburn took full advantage of the situation. For a few

seasons, students ran grease along the train tracks before Georgia Tech

games, making it impossible for the train to stop anywhere near the

station. Year after year, the poor football team ended up lugging its

gear a number of miles back to the station, giving the players more of a

warm-up than they bargained for and tilting the games in Auburn’s

favor.

13. Card Talk

Tricking

opposing fans into holding up placards that spell out a hidden message

is a prank older than time. It was perfected with the Great Rose Bowl

Hoax of 1961, during which students altered the placards given to

University of Washington fans so that the giant banner they formed read

“Caltech” on live television. The math and science school, which sits

just a few miles from the Rose Bowl, wasn’t even involved in the game.

14. The Elusive Northwest Tree-Dwelling Octopus

According

to the species’s official website, the Pacific Northwest tree octopus

is native to the rainforests of Washington State’s Olympic Peninsula.

It spends most of its time frolicking on treetops and snacking on frogs

and rodents. But today, the arboreal cephalopod faces extinction

thanks to rampant predation by the Sasquatch.

That last detail

gives away the joke to most people. But not everyone is so discerning.

The octopus’s meticulous creator—known online as Lyle Zapato—doesn’t

just throw hoaxes onto the web—he brilliantly links back to dozens of

external sites listing everything from short stories about tree

octopuses to videos of a baby tree octopus hatching to recipes for

cooking them. And he throws in just enough legitimate links to throw

readers off his scent. In fact, every statement is laboriously

cross-referenced; most Wikipedia pages would be lucky to have this many

sources.

Taken together, Zapato’s labyrinth of sites can trick

even savvy web surfers into thinking this tree-dwelling octopus exists.

A 2006 study by the University of Connecticut showed that 25 out of 25

web-proficient middle-schoolers fell for the hoax. Even when

researchers told them that tree octopuses don’t exist, the students

couldn’t identify the clues on the site to prove that it wasn’t

factual. The plight of the Pacific Northwest tree octopus is just one

of Zapato’s many causes; he maintains an elaborate site dedicated to

promoting the Bureau of Sasquatch Affairs and one that alleges that the

nation of Belgium doesn’t exist (the deceptive branding of Belgian

waffles fits into his conspiracy theory). Of course, whether you look

at it as art or entertainment, Zapato’s handiwork is a reminder not to

believe everything you read on the Internet.

Ever since Darwin published On the Origin of Species,

scientists have been looking for the missing link—a transitional

fossil that would seal the argument for human evolution. In 1912, an

amateur geologist and archaeologist named Charles Dawson found it. The

skull he pulled from a gravel pit in Piltdown, England, seemed to

conclusively fit the part, and the discovery rocked the scientific

community. Skeptics claimed the fossil was exactly what it looked like:

a human skull cobbled together with an ape jaw to fool gullible

scientists. In the ensuing excitement, believers shouted down deniers,

and in December 1912, the Geological Society of London hosted a

ceremony where Dawson presented his fossil, the Piltdown Man.

Ever since Darwin published On the Origin of Species,

scientists have been looking for the missing link—a transitional

fossil that would seal the argument for human evolution. In 1912, an

amateur geologist and archaeologist named Charles Dawson found it. The

skull he pulled from a gravel pit in Piltdown, England, seemed to

conclusively fit the part, and the discovery rocked the scientific

community. Skeptics claimed the fossil was exactly what it looked like:

a human skull cobbled together with an ape jaw to fool gullible

scientists. In the ensuing excitement, believers shouted down deniers,

and in December 1912, the Geological Society of London hosted a

ceremony where Dawson presented his fossil, the Piltdown Man.

First

Citizens Bank in Hull, Georgia, has several account holders with the

same name. But instead of double checking account numbers, they

deposited one man’s $31,000 into the account of an 18-year-old with the

same name. The teenager must have felt like he won the lottery, because

that’s how he acted. He withdrew $20,000 in cash and spent $5,000 with

his bank card. It was March 17, ten days after the deposit, before the

original depositor complained to the bank. Only then did the bank

discover the error.

First

Citizens Bank in Hull, Georgia, has several account holders with the

same name. But instead of double checking account numbers, they

deposited one man’s $31,000 into the account of an 18-year-old with the

same name. The teenager must have felt like he won the lottery, because

that’s how he acted. He withdrew $20,000 in cash and spent $5,000 with

his bank card. It was March 17, ten days after the deposit, before the

original depositor complained to the bank. Only then did the bank

discover the error.