Word

of the manuscript spread. In 1931, John M. Manly, a Chaucer expert at

the University of Chicago—who’d been “dabbling” with the manuscript for

years—published a paper that erased Newbold’s findings: Those

irregularities at the edge of the letters weren’t shorthand; they were

simply cracks in the ink.

But Manly’s discovery only fueled the

public’s desire to understand the mysterious manuscript. Before long,

experts from every field had joined the effort: Renaissance art

historians, herbalists, lawyers, British intelligence, and teams of

amateurs. Even William Friedman, who had led the team that solved

Japan’s “unbreakable” Purple cipher in World War II and had since

become head cryptanalyst at the National Security Agency, took a crack

at it. He never got close to solving it.

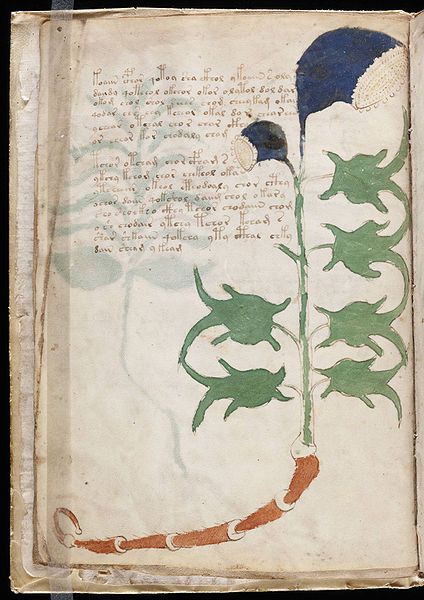

There are lots of

questions surrounding the Voynich manuscript, but the most essential

is: What is it? Because of the numerous illustrations of plants, many

believe the manuscript may be an herbalist’s textbook, written in some

kind of cipher or code—and the two terms are not synonymous.

Technically, a code can only be cracked if you have—or can figure

out—the guide to that code. A cipher is a more flexible algorithm, say,

where one letter is substituted for another. (For a simple example,

There

are a number of ways to crack a cipher, but one common technique is

frequency analysis. You count all the characters, find which are most

common, and match that against a similar pattern in a known language.

More elaborate ciphers might require different kinds of frequency

analysis or other mathematical methods.

What

Friedman saw—and what makes the Voynich so compelling—is that the text

isn’t random. There are clear patterns. “There’s a set number of

characters, an ‘alphabet’ with letters that repeat,” says Elonka Dunin, a

Nashville video game designer and author of

The Mammoth Book of Secret Codes and Cryptograms who

created her own page-for-page replica of the Voynich (just for fun!).

But she has doubts that the book is a cipher. “Ciphers back then were

just not that sophisticated. With modern computers, we can crack these

things quite quickly.” But a computer hasn’t yet, and that’s a red flag.

Back

in 1959, Friedman came to the same conclusion. Never able to crack the

code, he believed the text was “an early attempt to construct an

artificial or universal language of the a priori type”—in other words, a

language made up from scratch. Some agree. But others think the words

might be a language of another kind. Which brings us to Bax.

It took a split second

for Bax's Google results to confirm that kaur was a name in Indian

herbal guides for black hellebore. It was a match! “I almost jumped up

and down,” he says. “All of the months and months of work were starting

to show some cracks in the armor of the manuscript.” That night, he

couldn’t sleep. He kept going over the research in his head, expecting

to come up with a mistake.

If he was right—if certain words were

identifiable as plant names—then his findings agreed with Friedman: The

book was not a cipher. But unlike Friedman, Bax didn’t think the

language was made up. He was convinced that it resembled a natural

language. He’s not alone. One study of the Voynich, published in 2013

by Marcelo Montemurro and Damián Zanette, noted that statistical

analysis of the manuscript showed that the text has certain

organizational structures comparable to known languages. The most

commonly used words are relatively simple constructions (think the or

a), while more infrequent words, those that might be used to convey

specific concepts, have structural similarities, the way many verbs and

nouns do in other languages.

However,

there are quirks. In most languages, certain word combinations recur

frequently; but according to Zandbergen, that rarely happens in the

Voynich. The words tend to have a prefix, a root, and a suffix, and

while some have all three, others have only one or two. So you can get

words that combine just a prefix and a suffix—

uning, for

example. Further, there are no two-letter words or words with more than

10 characters, which is strange for a European language. That’s enough

to put some people off the idea that it could be a natural language.

When

Bax started working with the text, he treated it like Egyptian

hieroglyphics. He borrowed an approach used by Thomas Young and

Jean-François Champollion, who in 1822 used the proper names of

pharaohs—easy to identify because they were marked with a special

outline—to work backward, assigning sound values to the symbols and then

extrapolating other words from these. This was something that, Bax

says, no one had systematically attempted on the Voynich.

The

first proper name Bax identified was a word next to an illustration of

a group of stars resembling Pleiades. “People before us suggested that

that particular word is probably related to Taurus,” he says. “If you

assume it says

Taurus, the first sound must be a ta, or somewhere in that region—ta, da,

Taurus, Daurus.”

The process seems insanely daunting at first: “On the basis of one

word alone, that’s just complete imagination,” he says. “But then you

take that possible

ta sound and you look at other possible proper nouns through the manuscript and see if you can see a pattern emerging.”

Bax worked for a year and a half, deciphering crumbs of letter-sound correspondences. Eight months after he confirmed

hellebore,

he published a paper online detailing his method. He cautiously

announced the “provisional and partial” decoding of 10 words, including

juniper, hellebore, coriander, nigella sativa, Centaurea, and the constellation

Taurus.

"University

of Bedfordshire professor cracks code to mysterious 15th-century

Voynich manuscript," the local paper blared. Quickly, news

organizations around the world joined in.

Nothing major happens

in the long saga of the Voynich without media hype. The last time it

had happened, in 2004, a British computer scientist named Gordon Rugg

had published a paper showing that the whole thing might be an

elaborate hoax created expressly to separate a wealthy buyer from a lot

of money. And where there’s media controversy, there’s contention among

Voynich obsessives. Rugg says his theory was like “someone grabbing

the football and walking off the pitch in the middle of a really fun

game.”

Bax’s

proclamation came with its share of controversy, too. People in the

Voynich world have seen a lot of so-called cracks over the years, none

of which have panned out, so when the news stories appeared on Bax’s

paper, Dunin, the video game designer, just laughed. “The media just

picks it up uncritically and says, ‘He must have solved it.’ He

didn’t,” she says. “He’s saying, ‘I saw this, and this looked

intriguing,’ and that’s perfectly valid. But it’s not a crack.” Others

criticized his methods: Some had issues with the idea that the first

word on a page is a plant name, because many of those words start with

one of only two letters. Some found it weird that his translation has

three different characters that stand for the letter

r.

Bax

doesn’t claim he’s cracked the code. “I’m prepared to see that some of

the interpretations I’ve suggested are revised or even thrown out,” he

says. “That’s the way you make progress on something like this. But

I’m pretty convinced that a lot of it is solid.”

He’s determined

to prove it, by stoking more dialogue within the obsessive community.

In addition to the Voynich Wikipedia page, there’s an entire Wiki

devoted to the book’s oddities and the efforts to crack it. Mailing

lists started in the early 1990s are still going strong. Reddit, too,

has taken an interest, and when Bax did an AMA after publishing his

paper, it got 100,000 pageviews. Bax himself has set up

a website to

document his efforts. He actively encourages participation, fielding

comments from visitors eager to help him decode the book.

One such

volunteer is Milan-based Marco Ponzi, who had been researching Tarot

card history when he found Bax’s paper. Ponzi began commenting on Bax’s

website, suggesting there might be parallels between certain diagrams

in the volume and images that appear in the Tarot. “Since Stephen is so

rigorous and so kind, I feel encouraged to propose new ideas,” he

says. “I don’t know if I have contributed anything really useful, but

it is very fun.”

“Marco

is bringing his expertise in medieval art, iconography, and Italian

manuscripts—which I don’t have,” says Bax. “This is one of the beauties

of doing it through the web.” Indeed, it’s become an international

collaboration. Bax has asked other readers to add their own

observations in the comments section, and spends a lot of time

responding to queries and participating in the discussion. In the

future, he hopes to host conferences and seminars about the book, and to

set up a site where he can crowdsource efforts to decode other Voynich

sections. If the method works, he expects that the manuscript could be

decoded within four years.

What will be revealed when—and if— it

is? Bax believes the manuscript is a treatise on the natural world,

written in a script invented to record a previously unwritten language

or dialect—possibly a Near Eastern one—created by a small community

that later disappeared. “If it did turn out to be from a group of

people who have disappeared,” he says, “it could unlock a whole area of

a particular country or a group that is completely unknown to us.”

Other

theories put forth that the secrets locked inside the Voynich’s vellum

pages could reveal a coming apocalypse—or merely the details of

medieval hygiene. Some people think the script could be the observations

of a traveler who was trying to learn a language like Arabic or

Chinese, or a stream-of-consciousness recording of someone in a trance.

The most bizarre theories involve aliens or a long-lost underground

race of lizard people.

It’s possible that the book will never

tell us anything. To Zandbergen, whether it has huge secrets to reveal

doesn’t matter at all. He just wants to know why the book was written.

Whether it’s the work of a hoaxer, an herbalist, or a lizard person,

the Voynich is important all the same. “It’s still a manuscript from

the 15th century. It has historical value,” he says. But until the

truth is revealed—and probably even after—people will keep trying to

crack the Voynich. After all, who doesn’t love a good puzzle?

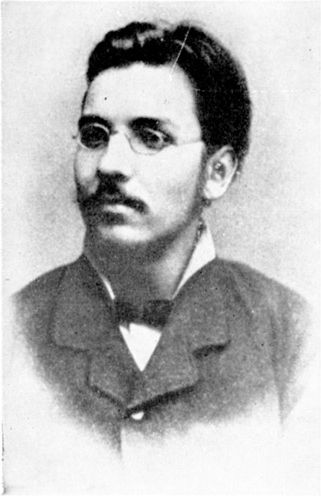

The

story starts with a London-based book dealer named Wilfrid Voynich,

who discovered the book in 1912. From the beginning, Voynich was

evasive about how he acquired the tome—he claimed he’d been sworn to

secrecy about its origin, and the story he recounted changed often. In

the one he told most frequently, he’d been at “an ancient castle in

Southern Europe” when he found this “ugly duckling” buried in a “most

remarkable collection of precious illuminated manuscripts.”

The

story starts with a London-based book dealer named Wilfrid Voynich,

who discovered the book in 1912. From the beginning, Voynich was

evasive about how he acquired the tome—he claimed he’d been sworn to

secrecy about its origin, and the story he recounted changed often. In

the one he told most frequently, he’d been at “an ancient castle in

Southern Europe” when he found this “ugly duckling” buried in a “most

remarkable collection of precious illuminated manuscripts.”