Patients with Locked-in Syndrome

In the Dalton Trumbo novel Johnny Got His Gun,

a horribly wounded soldier loses his arms, legs, and face. He keeps his

wits, but is unable to communicate for a long time. When he can finally

let those around him know that he is still conscious, they ask him what

he wants. When he gives his answer, he is denied his only request. That

nightmare is a possibility for many people thanks to new technology.

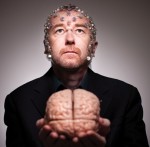

Neuroscientist Adrian Owen works to communicate with patients who are

thought to be in a vegetative state, but may be victims of Locked-In

Syndrome. Owen looks at brain function during fMRI scanning and tries to

discern whether increased activity in parts of the brain are attempts

to answer questions or communicate. He has had some success with several

patients.

In the Dalton Trumbo novel Johnny Got His Gun,

a horribly wounded soldier loses his arms, legs, and face. He keeps his

wits, but is unable to communicate for a long time. When he can finally

let those around him know that he is still conscious, they ask him what

he wants. When he gives his answer, he is denied his only request. That

nightmare is a possibility for many people thanks to new technology.

Neuroscientist Adrian Owen works to communicate with patients who are

thought to be in a vegetative state, but may be victims of Locked-In

Syndrome. Owen looks at brain function during fMRI scanning and tries to

discern whether increased activity in parts of the brain are attempts

to answer questions or communicate. He has had some success with several

patients.Owen’s discovery1, reported in 2010, caused a media furore. Medical ethicist Joseph Fins and neurologist Nicholas Schiff, both at Weill Cornell Medical College in New York, called it a “potential game changer for clinical practice”2. The University of Western Ontario in London, Canada, soon lured Owen away from Cambridge with Can$20 million (US$19.5 million) in funding to make the techniques more reliable, cheaper, more accurate and more portable — all of which Owen considers essential if he is to help some of the hundreds of thousands of people worldwide in vegetative states. “It’s hard to open up a channel of communication with a patient and then not be able to follow up immediately with a tool for them and their families to be able to do this routinely,” he says.On the surface, allowing such patients to have a say in their own future seems to be the humane thing to do. But how can we assess a patient’s intellectual ability and competence with such new technology? And how can we judge a patent’s mental health under such grim circumstances? And even if those questions are put to rest, what is the right thing to do? This is not just a theoretical argument. Tony Nicklinson, who can only communicate by moving his eyes, will petition a court next week to allow his doctor to legally end his life. Adrian Owen’s communication technique may uncover other patients with the same wish. But he is not ready to ask them yet.

Many researchers disagree with Owen’s contention that these individuals are conscious. But Owen takes a practical approach to applying the technology, hoping that it will identify patients who might respond to rehabilitation, direct the dosing of analgesics and even explore some patients’ feelings and desires. “Eventually we will be able to provide something that will be beneficial to patients and their families,” he says.

Still, he shies away from asking patients the toughest question of all — whether they wish life support to be ended — saying that it is too early to think about such applications. “The consequences of asking are very complicated, and we need to be absolutely sure that we know what to do with the answers before we go down this road,” he warns.

No comments:

Post a Comment