If you thought recycling was just a modern phenomenon championed by environmentalists and concerned urbanites - think again.

"For the first time we are revealing the extent of this phenomenon, both

in terms of the amount of recycling that went on and the different

methods used," said Ran Barkai, an archaeologist and one of the

organizers of the four-day gathering at Tel Aviv University that ended

Thursday.

Just as today we recycle materials such as paper and plastic to

manufacture new items, early hominids would collect discarded or broken

tools made of flint and bone to create new utensils, Barkai said.

The behavior "appeared at different times, in different places, with

different methods according to the context and the availability of raw

materials," he told The Associated Press.

From caves in Spain and North Africa to sites in Italy and Israel,

archaeologists have been finding such recycled tools in recent years.

The conference, titled "The Origins of Recycling," gathered nearly 50

scholars from about 10 countries to compare notes and figure out what

the phenomenon meant for our ancestors.

Recycling was widespread not only among early humans but among our

evolutionary predecessors such as Homo erectus, Neanderthals and other

species of hominids that have not yet even been named, Barkai said.

Avi Gopher, a Tel Aviv University archaeologist, said the early

appearance of recycling highlights its role as a basic survival

strategy. While they may not have been driven by concerns over pollution

and the environment, hominids shared some of our motivations, he said.

"Why do we recycle plastic? To conserve energy and raw materials,"

Gopher said. "In the same way, if you recycled flint you didn't have to

go all the way to the quarry to get more, so you conserved your energy

and saved on the material."

"I think it was just something you picked up unconsciously and used to

make something else," Barsky said. "Only after years and years does this

become systematic."

That started happening about half a million years ago or later, scholars said.

For example, a dry pond in Castel di Guido, near Rome, has yielded bone

tools used some 300,000 years ago by Neanderthals who hunted or

scavenged elephant carcasses there, said Giovanni Boschian, a geologist

from the University of Pisa.

"We find several levels of reuse and recycling," he said. "The bones

were shattered to extract the marrow, then the fragments were shaped

into tools, abandoned, and finally reworked to be used again."

At other sites, stone hand-axes and discarded flint flakes would often

function as core material to create smaller tools like blades and

scrapers. Sometimes hominids found a use even for the tiny flakes that

flew off the stone during the knapping process.

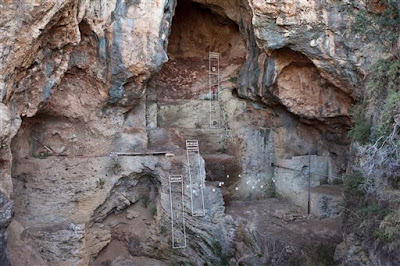

At Qesem cave, a site near Tel Aviv dating back to between 200,000 and

420,000 years ago, Gopher and Barkai uncovered flint chips that had been

reshaped into small blades to cut meat - a primitive form of cutlery.

Some 10 percent of the tools found at the site were recycled in some

way, Gopher said. "It was not an occasional behavior; it was part of the

way they did things, part of their way of life," he said.

He said scientists have various ways to determine if a tool was

recycled. They can find direct evidence of retouching and reuse, or they

can look at the object's patina - a progressive discoloration that

occurs once stone is exposed to the elements. Differences in the patina

indicate that a fresh layer of material was exposed hundreds or

thousands of years after the tool's first incarnation.

Some participants argued that scholars should be cautious to draw

parallels between this ancient behavior and the current forms of

systematic recycling, driven by mass production and environmental

concerns.

"It is very useful to think about prehistoric recycling," said Daniel

Amick, a professor of anthropology at Chicago's Loyola University. "But I

think that when they recycled they did so on an `ad hoc' basis, when

the need arose."

Participants in the conference plan to submit papers to be published

next year in a special volume of Quaternary International, a

peer-reviewed journal focusing on the study of the last 2.6 million

years of Earth's history.

Norm Catto, the journal's editor in chief and a geography professor at

Memorial University in St John's, Canada, said that while prehistoric

recycling had come up in past studies, this was the first time experts

met to discuss the issue in such depth.

Catto, who was not at the conference, said in an email that studying

prehistoric recycling could give clues on trading links and how much

time people spent at one site.

Above all, he wrote, the phenomenon reflects how despite living

millennia apart and in completely different environments, humans appear

to display "similar responses to the challenges and opportunities

presented by life over thousands of years."

No comments:

Post a Comment