Researchers now have stronger evidence of granite on Mars and a new

theory for how the granite -- an igneous rock common on Earth -- could

have formed there, according to a new study. The findings suggest a much

more geologically complex Mars than previously believed.

"We're providing the most compelling evidence to date that Mars has

granitic rocks," said James Wray, an assistant professor in the School

of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences at the Georgia Institute of Technology

and the study's lead author.

The research was published November 17 in the Advance Online Publication of the journal Nature Geoscience. The work was supported by the NASA Mars Data Analysis Program.

For years Mars was considered geologically simplistic, consisting mostly

of one kind of rock, in contrast to the diverse geology of Earth. The

rocks that cover most of Mars's surface are dark-colored volcanic rocks,

called basalt, a type of rock also found throughout Hawaii for

instance.

But earlier this year, the Mars Curiosity rover surprised scientists by

discovering soils with a composition similar to granite, a

light-colored, common igneous rock. No one knew what to make of the

discovery because it was limited to one site on Mars.

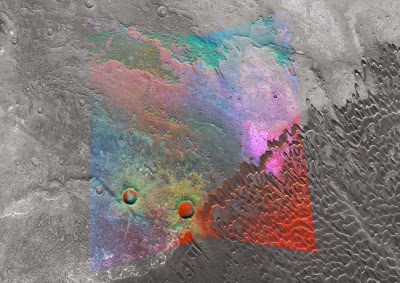

The new study bolsters the evidence for granite on Mars by using remote

sensing techniques with infrared spectroscopy to survey a large volcano

on Mars that was active for billions of years. The volcano is dust-free,

making it ideal for the study. Most volcanoes on Mars are blanketed

with dust, but this volcano is being sand-blasted by some of the

fastest-moving sand dunes on Mars, sweeping away any dust that might

fall on the volcano. Inside, the research team found rich deposits of

feldspar, which came as a surprise.

"Using the kind of infrared spectroscopic technique we were using, you

shouldn't really be able to detect feldspar minerals, unless there's

really, really a lot of feldspar and very little of the dark minerals

that you get in basalt," Wray said.

The location of the feldspar and absence of dark minerals inside the

ancient volcano provides an explanation for how granite could form on

Mars. While the magma slowly cools in the subsurface, low density melt

separates from dense crystals in a process called fractionation. The

cycle is repeated over and over for millennia until granite is formed.

This process could happen inside of a volcano that is active over a long

period of time, according to the computer simulations run in

collaboration with Josef Dufek, who is also an associate professor in

the School of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences at Georgia Tech.

"We think some of the volcanoes on Mars were sporadically active for

billions of years," Wray said. "It seems plausible that in a volcano you

could get enough iterations of that reprocessing that you could form

something like granite."

This process is sometimes referred to as igneous distillation. In this

case the distillation progressively enriches the melt in silica, which

makes the melt, and eventual rock, lower density and gives it the

physical properties of granite.

"These compositions are roughly similar to those comprising the plutons

at Yosemite or erupting magmas at Mount St. Helens, and are dramatically

different than the basalts that dominate the rest of the planet," Dufek

said.

Another study published in the same edition of Nature Geoscience by a

different research team offers another interpretation for the

feldspar-rich signature on Mars. That team, from the European Southern

Observatory and the University of Paris, found a similar signature

elsewhere on Mars, but likens the rocks to anorthosite, which is common

on the moon. Wray believes the context of the feldspar minerals inside

of the volcano makes a stronger argument for granite. Mars hasn't been

known to contain much of either anorthosite or granite, so either way,

the findings suggest the Red Planet is more geologically interesting

than before.

"We talk about water on Mars all the time, but the history of volcanism

on Mars is another thing that we'd like to try to understand," Wray

said. "What kinds of rocks have been forming over the planet's history?

We thought that it was a pretty easy answer, but we're now joining the

emerging chorus saying things may be a little bit more diverse on Mars,

as they are on Earth."

This research is supported by the NASA Mars Data Analysis Program under

award NNX13AH80G. Any conclusions or opinions are those of the authors

and do not necessarily represent the official views of the sponsoring

agencies.

No comments:

Post a Comment