Of

the three eating utensils we normally use, only forks have a modern

origin. Knives and spoons are prehistoric- but as recently as 1800,

forks weren’t commonly used in America. Some food for thought…

KNIVES, BUT NO FORKS

Of

the three eating utensils we normally use, only forks have a modern

origin. Knives and spoons are prehistoric- but as recently as 1800,

forks weren’t commonly used in America. Some food for thought…

KNIVES, BUT NO FORKS

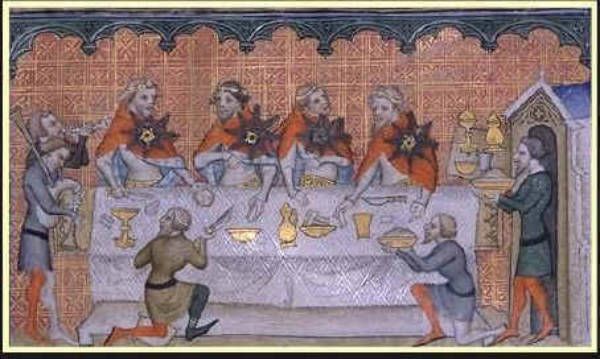

Centuries

ago, few people had ever heard of a “place setting.” When a large piece

of meat was set on the table (sometimes on a platter, sometimes

directly on the table), diners grabbed the whole thing with their free

hand… then pulled out a knife and sliced off a piece with their other

hand. Most eating was done with fingers: Common people ate with all

five, while nobles -who understood sophisticated table manners- ate with

only three (thumb, forefinger, and middle).

At that time, there

were no utensils. In fact, most men owned just one multipurpose blade,

which, in addition to carving food, was used for fighting, hunting, and

butchering animals. But wealthy nobles had always been able to afford a

different knife for each purpose, and by the Middle Ages, they had

developed a setting of

two knives, for very formal dining. One

knife was thrust into a large piece of meat to hold it in place on a

plate, while the second was used to cut off a smaller piece, which the

eater speared and placed in is mouth.

FORKS

One

of the drawbacks of cutting a piece of meat while holding it in place

with a knife is that the meat has a tendency to “rotate in place like a

wheel on an axle,” Henry Petroski writes in

The Evolution of Useful Things.

“Frustration with knives, especially in their shortcoming in holding

meat steady for cutting, eventually led to the development of the fork.”

The name comes from

furca, the Latin word for a farmer’s pitchfork.

The

first fork commonly used in Europe was a miniature version of the big

carving fork used to spear turkeys and roasts in the kitchen. It had

only two “tines” or prongs, spaced far enough apart to hold meat in

place while cutting it; but apparently it wasn’t something you stuck in

your mouth and ate with -that was still the knife’s job.

A FOOLISH UTENSIL

Those

first table forks probably originated at the royal courts of the Middle

East, where they were in use as early as the seventh century. About

1100 AD they appeared in the Tuscany region of Italy, but they were

considered “shocking novelties,” and were ridiculed and condemned by

clergy, who insisted that “only human fingers, created by god, were

worthy to touch god’s bounty.” Forks were “effeminate pieces of finery,”

as one historian puts it, used by sinners and sissies but not by

decent, God-fearing folk.

“An Italian historian recorded a dinner at which a Venetian noblewoman used a fork of her own design,” Charles Panati write in The Extraordinary Origins of Ordinary Things,

“and incurred the rebuke of several clerics present for her ‘excessive

sign of refinement.’ The woman died days after the meal, supposedly from

the plague, but clergymen preached that her death was divine

punishment, a warning to others contemplating the affectation of a

fork.”

FORK YOU

Early French Forks

Thanks

to these derogatory associations, more than 250 years passed before

forks finally came into wide use in Italy. In the rest of Europe they

were virtually unheard of. Catherine de Medici finally brought them to

France in the 1500s when she became queen. And in 1608 an Englishman

named Thomas Coryate traveled to Italy and saw people eating with forks;

the sight was so peculiar that he made note of it in his book Crudities Hastily Gobbled Up in Five Months:

The

Italians… do always at their meals use a little fork when they cut

their meat… Should [anyone] unadvisedly touch the dish of meat with his

fingers from which all at the table do cut, he will give occasion of

offense unto the company, as having transgressed the laws of good

manners, insomuch that for his error he shall be at least browbeaten if

not reprehended in words… The Italian cannot by any means indure to have

his dish touched with fingers, seeing all men’s fingers are not alike

clean.

Coryate brought some forks with him to England

and presented one to Queen Elizabeth, who was so thrilled by the

utensil that she had additional ones made from gold, coral, and crystal.

But they remained little more than a pretentious fad of the royal

court.

Fork Use 1624

Forks

became more popular during the late 17th century, but it wasn’t until

the 18th century that they were widely used in continental Europe as a

means of conveying food “from plate to mouth.” The reason: French nobles

saw forks as a way to distinguish themselves from commoners. “The fork

became a symbol of luxury, refinement, and status,” writes Charles

Panati. “Suddenly, to touch food with even three bare fingers was

gauche.” A new custom developed- when an invitation to dinner was

received, a servant frequently was sent ahead with a fine leather case

containing a knife, fork, and spoon to be used at dinner later.

MAKING A NEW POINT

Édouard Manet's Oysters 1862

But

before this revolution took place, the fork had to be redesigned. The

first forks were completely useless when it came to scooping peas and

other loose food into the mouth- the gap between the tines was too

large. So cutlery makers began adding a third tine to their forks, and

by the early 18th century, a fourth. “Four appears to have been the

optimum [number],” Henry Petroski writes in The Evolution of Useful Things.

“Four tines provide a relatively broad surface and yet do not feel too

wide for the mouth. Nor does a four-tined fork have so many tines that

it resembles a comb, or function like one when being pressed into a

piece of meat.”

COMING TO AMERICA

One of

the last places the fork caught on in the Western world was colonial

America. In fact, forks weren’t even commonly used until the time of the

Civil War; until then, people just ate with knives or their fingers. In

1828, for example, the English writer Francis Trollope wrote of some

general, colonels, and majors aboard a Mississippi steamboat who had

“the rightful manner of feeding with their knives, tip the whole blade

seemed the enter the mouth.” And as late as 1864, one etiquette manual

complained that “many persons hold forks awkwardly, as if not accustomed

to them.”

No comments:

Post a Comment