Especially if you’re a diplomat, soldier or spy, says one ex-spook

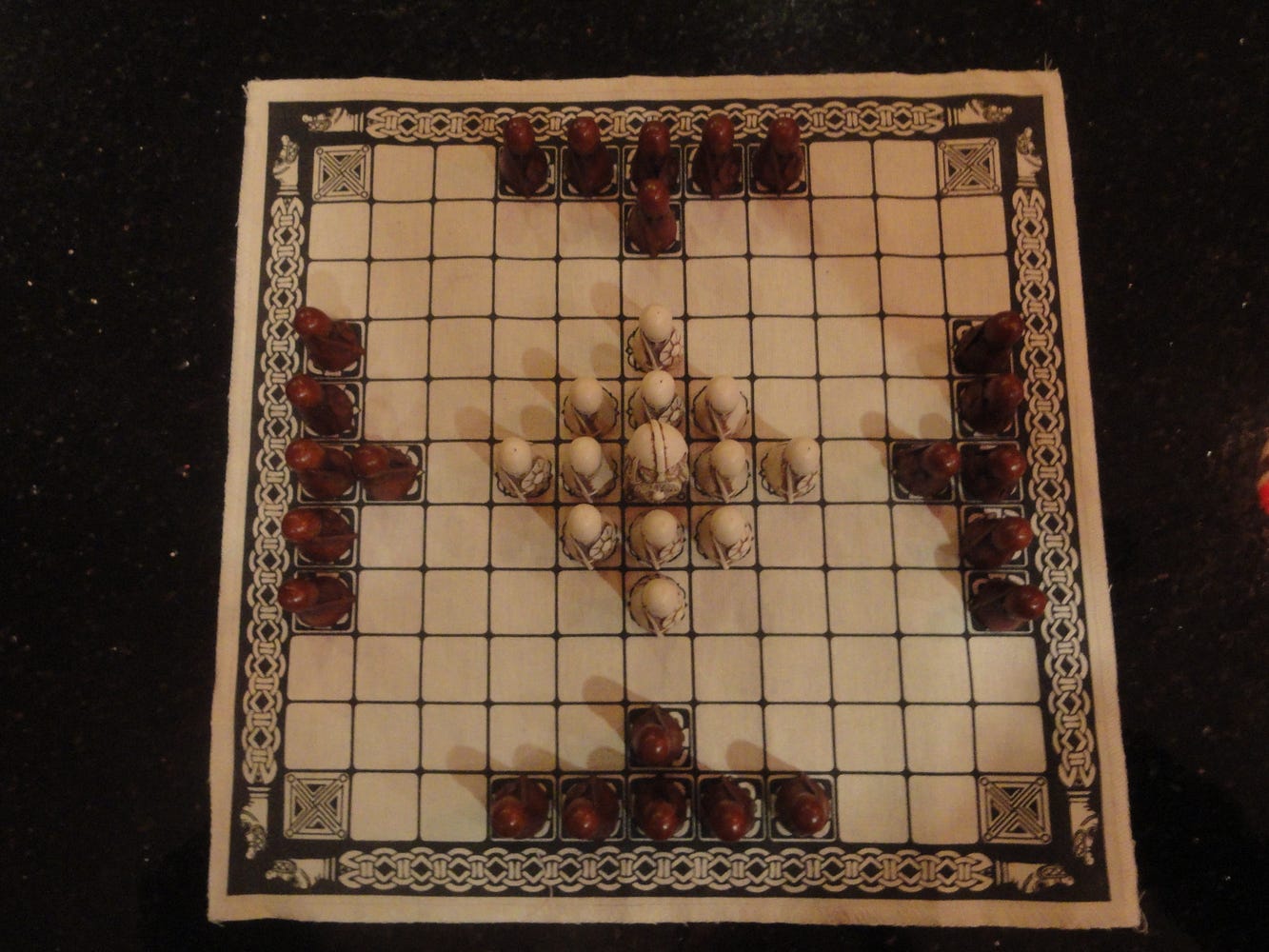

Viking

warriors storm into the torch-lit camp of a rival clan. Outnumbered,

the ambushed Norsemen are far from their boats. Their one goal: flee to a

nearby castle while keeping their king alive.

At

first glance, Hnefatafl (prounounced “nef-ah-tah-fel”) might just look

like a knock-off version of chess with Norse helms and impressive

beards, but the game is at least 600 years older—already well-known by

400 A.D.—and is perhaps a lot more relevant to the conflicts of the 21st

century.

“I love the

asymmetry in this game. To win in this game, you absolutely have to

think like your opponent,” emails Kristan Wheaton, a former Army foreign

area officer and ex-analyst at U.S. European Command’s Intelligence

Directorate. “Geography, force structure, force size and objectives are

different for the two sides. If you can’t think like your opponent, you

can’t win. I don’t know of a better analogy for post-Cold War conflict.”

The

game is similar to chess, but with several important differences.

Instead of two identical and equal opponents facing each other,

Hnefatafl is a game where one side is surrounded and outnumbered—like a

Viking war party caught in an ambush.

The game might seem

unbalanced. The attacking black player has 24 total pieces—known as

“hunns”—to white’s meager and surrounded 12 hunns. But white has several

advantages.

White

has an additional unique unit, a king, which must be surrounded on four

horizontal sides to be captured. Hunns require being surrounded on two

sides, and that’s pretty hard by itself. White’s goal is also simple:

move the king to one of four corner squares known as “castles.” Black’s

goal is to stop them.

Other

rules? All pieces move like chess rooks. Black makes the first move.

Black cannot occupy a castle, which would end the game in short order.

But black can block off several castles by moving quickly, forming the equivalent of a medieval shield wall.

“If

the king goes as hard as he can as early as he can for the corner and

the other side is not really on its toes, the non-king side typically

loses in just a few turns,” adds Wheaton, who now teaches intelligence

studies at Mercyhurst University. “Among experienced players, however,

this rarely happens.”

If

lines are solid, they have to be flanked. Thus, it’s in black’s

interest to force a symmetrical battle to force a likely win. If white

can avoid engaging in a battle on black’s terms, then white’s chances of

winning improve.

This

was especially true at the time period this game was played, when

battles were largely skirmishes and sieges, and before heavy cavalry

arrived on the scene. Two warring sides would sit opposite each other,

hacking away until the loser was either exhausted or flanked.

“Hnefatafl

seems to teach a number of lessons to young Viking warriors,” Wheaton

explains. “For example, it takes two soldiers to ‘kill’ an enemy

(elementary battle tactics?), the king is the most important piece on

the board (reinforcing the social order?), and, surrounded and cut off,

it is easier (in novice games) for the smaller force to win (morale

booster?). Someone analyzing the Vikings might learn a good bit about

how they fight and what they value (and what they fear) by playing this

game.”

That’s how,

Wheaton notes, the game gives insight for generals, diplomats and spies

tasked with fighting, besting—or at least—understanding what an enemy or

rival thinks.

Hnefatafl

is a Viking’s worst case scenario: Outnumbered, cut off from their

boats—and on the verge of being massacred. Understanding the game played

by Viking war parties on the way to raid England of its booty meant

understanding something about the way the Vikings saw themselves. The

total time spent playing the game may have been more than any individual

warrior spent sacking the Anglo-Saxons, for instance.

“I

think the games cultures play can help intelligence professionals

understand something about the way cultures think about strategy. Much

of the language of strategy gets re-cast as the language of the game,”

Wheaton adds.

“There

is no U.S. military officer who would not know what his or her boss

meant if the boss said, ‘we are going to do an end-run on them’ and no

U.S. official would misunderstand ‘It’s fourth and 10 and we have to

punt.’ These kinds of games produce a common strategic language that

cuts across bureaucratic lines. The military and the State Department

may not understand each other but they both understand American

football.”

More than that, understanding the games people play might help you learn more about how they operate.

Maybe Wheaton is overthinking it … or maybe not. “[Barack Obama’s] got the personality of a sniper,” journalist Michael Lewis said after watching one of Obama’s pick-up basketball games for a Vanity Fair profile.

A commentary on drones, perhaps? George W. Bush used his co-ownership

of the Texas Rangers baseball team to boost his business credentials

during his first presidential campaign. And what about Vladimir Putin?

He has a black belt in judo.

“I

don’t want to make more of this than it deserves,” Wheaton wrote, “but

it seems logical to me, if I am very interested in a senior leader of a

foreign country, to ask, ‘What game does he like to play?’”

No comments:

Post a Comment