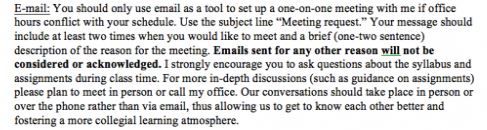

Pictured above is a screenshot from a course syllabus produced by Dr. Spring-Serenity Duvall, a professor of media and gender studies

at Salem College in North Carolina. During the Spring semster of 2014,

she prohibited students from emailing her unless they were requesting an

appointment to speak with her face-to-face.

Pictured above is a screenshot from a course syllabus produced by Dr. Spring-Serenity Duvall, a professor of media and gender studies

at Salem College in North Carolina. During the Spring semster of 2014,

she prohibited students from emailing her unless they were requesting an

appointment to speak with her face-to-face.Dr. Duvall is no Luddite. She's simply tired of students asking her questions that she already answered in class or in the syllabus, or addressing her in an overly familiar manner. She explains what she changed:

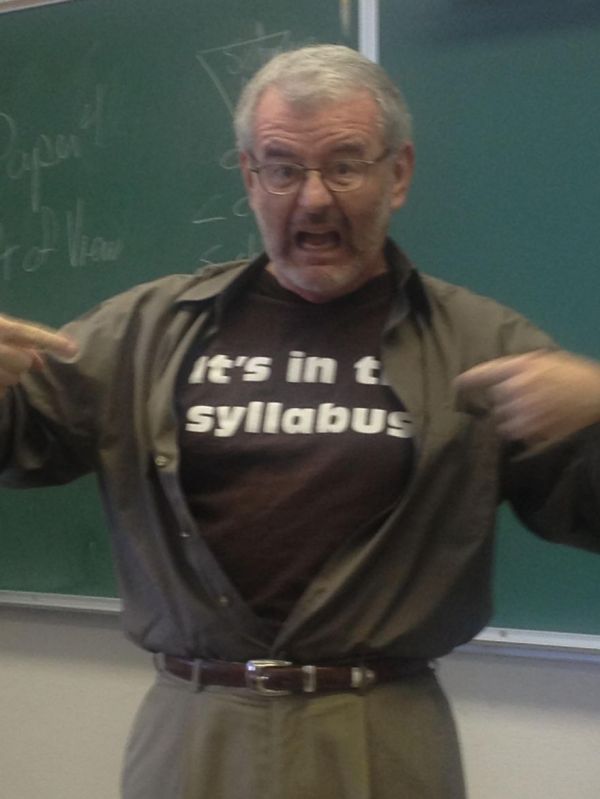

In a fit of self-preservation, I decided: no more. This is where I make my stand! In my senior-level gender and media course, I instituted a no-email policy and (here’s the hard part) stuck to it religiously. I explained to my students that there were a few very solid reasons for this policy:Did it work? Yes!

1. They needed to read and know the syllabus and pay attention in class, rather than use email as a crutch to ask superficial questions. Taking these small yet seemingly impossible steps would make them more aware and engaged in the class.

2. Reading assignment instructions carefully and asking questions about the assignments in class or in office hours would force them to begin working on papers early, thus eliminating last-minute emails about instructions.

3. More of our conversations would take place in person – whether in my office or in class – rather than via email, thus allowing us to get to know each other better and fostering a more collegial atmosphere.

I am happy to report it was an unqualified success. It’s difficult to convey just how wonderful it was for students to stop by office hours more often, to ask questions about assignments in the class periods leading up to due dates, and to have students rise to the expectation that they know the syllabus. Their papers were better, they were more prepared for class time than I’ve ever experienced.

It is also difficult to tally the time I saved by not answering hundreds of brief, inconsequential emails throughout the semester. I can say that the difference in my inbox traffic was noticeable and welcome.

In an interview, Dr. Duvall explains that, like many professors, she suffers from "syllabus creep." That's "where the syllabus just gets longer and longer and you try to account for everything." The longer a syllabus gets, the less likely a student is to read the whole thing.

And course syllabi are getting a lot longer. Slate's Rebecca Shuman offers an explanation of why syllabi are now often 20 or more pages long:

First, the helicopter generation—raised on both suffocating parental pressure and the teach-to-the-test mandates of No Child Left Behind—started coming to college. Everyone needed A’s, and everyone needed to know exactly what needed to be done to get one. When that wasn’t abundantly clear, that made schools vulnerable to lawsuits.

Second, syllabi went from print to online, thus freeing the entire professoriate to capitulate to the aforementioned demands for everything from grading rubrics to the day-by-day breakdown of late assignment policies, without worrying about sacrificing trees or intimidating the class with a first-day handout they could barely lift, much less peruse in a mere 75 minutes.

Third, the skyrocketing percentage of hired-gun adjuncts—as opposed to tenure-track faculty, who have both a modicum of security and a minuscule say in university governance—meant that a substantial number of instructors were taking on courses a matter of weeks (sometimes days) before they began. Thus, they relied heavily on extensive syllabi already in existence.

No comments:

Post a Comment