How Charles Dickens fueled a world of spontaneous combustion truthers.

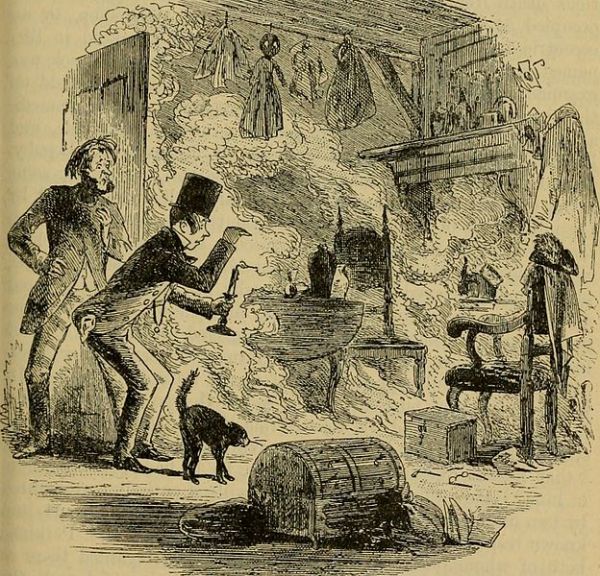

The first thing they noticed was the smell—like

someone frying rancid meat. The two men sat in their flat in central

London, awaiting their midnight appointment with the old, alcoholic Mr.

Krook, who lived downstairs. As they chatted uneasily, ominous sights

and smells kept distracting them. Black soot swirled through the room. A

pungent yellow grease stained the windowsill. And that smell!

At

last, after midnight, they descended the stairs. Mr. Krook’s

shop—crammed with dirty rags, bottles, bones, and other hoarded

trash—was unpleasant even in daytime. But tonight they sensed something

positively evil. Outside Krook’s bedroom near the back of the shop, a

cat leaped out and snarled. When they entered Krook’s room, the odor

choked them. Grease stained the walls and ceiling as if it were painted

on. Krook’s coat and cap lay on a chair; a bottle of gin sat on the

table. But the only sign of life was the cat, still hissing. The men

swung their lantern around, looking for Krook, who was nowhere to be

seen.

Then they saw the pile of ash on the floor. They stared for a

moment, before turning and running. They burst onto the street,

shouting for help. But it was too late: Old Krook was gone, a victim of

spontaneous combustion.

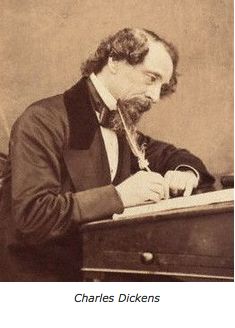

When Charles Dickens published this scene in December 1852—an installment from his serialized novel

Bleak House—most

readers swallowed it as fact. After all, Dickens wrote realistic

stories, and he took great pains to render scientific matters like

smallpox infections and neurological disorders accurately. So even

though Krook was fictional, the public trusted that Dickens had

portrayed spontaneous combustion with his customary precision.

Most

of the public, anyway. A few readers were outraged by the scene. After

all, scientists had been laboring to debunk old nonsense like

clairvoyance, mesmerism, and the idea that people sometimes burst into

flames. And key discoveries about heat, electricity, and other phenomena

provided strong support for their view, showing that the human body,

far from being otherworldly, was subject to all physical laws of nature.

But the science was still behind. And there were enough mysteries for

old wives’ tales to retain a foothold. This only made both sides more

desperate to prove their case, and within two weeks skeptics began

challenging Dickens in print, inciting one of the strangest

controversies in literary history.

Leading the charge was George Lewes, a Victorian-era Richard

Dawkins—always ready to attack superstitions. Lewes had studied

physiology as a young man, so he understood the body. He also had a foot

in the literary world as a critic and playwright and as George Eliot’s

longtime lover. In fact, he counted Dickens as a friend.

But you wouldn’t know that from Lewes’s response to the story. Writing in the newspaper

The Leader,

he acknowledged that artists have a license to bend the truth, but

protested that novelists can’t just ignore the laws of physics. “The[se]

circumstances are beyond the limits of acceptable fiction,” he wrote,

“and give credence to a scientific impossibility.” He accused Dickens

of cheap sensationalism and “of giving currency to a vulgar error.”

Dickens swung back. Since he published a new installment of

Bleak House

each month, he had time to slip a rejoinder into the next episode. As

the action picks back up with the inquest into Krook’s death, Dickens

mocks his critics as eggheads too blind to see plain evidence: “Some of

these authorities (of course the wisest) hold with indignation that the

deceased had no business to die in the alleged manner,” Dickens wrote.

To them, “going out of the world by any such by-way [was] wholly

unjustifiable and personally offensive.” But common sense eventually

triumphs, and the coroner in the story declares, “These are mysteries we

can’t account for!”

In

private letters to Lewes, Dickens continued his defense, mentioning

several historical cases of spontaneous combustion throughout history.

He leaned especially hard on the case of an Italian countess who had

reportedly combusted in 1731. She bathed in camphorated spirits of wine

(a mixture of brandy and camphor); the morning after one such bath,

her maid walked into her room to find the bed unslept on. As with Mr.

Krook, soot hung suspended in the air, along with a yellow haze of oil

on the windows. The maid found the countess’s legs—just her

legs—standing several feet from the bed. A pile of ashes sat between

them, along with her charred skull. Nothing else seemed amiss, except

for two melted candles nearby. And because a priest had recorded this

tale, Dickens considered it trustworthy.

He wasn’t the only author

to write about spontaneous combustion. Mark Twain, Herman Melville,

and Washington Irving all had characters erupt as well. Much like the

“nonfiction” accounts they drew from, most of the victims were old,

sedentary alcoholics. Their torsos always burned completely, but their

extremities often survived intact. Eerier still, beyond the occasional

scorch mark on the floor, the flames never consumed anything but the

victim’s body. The strangest part? Dickens and others did have some

science backing them up.

Spontaneous combustion was

linked to one of the most important discoveries in medical history,

one that revolutionized our understanding of how the body worked—the

discovery of oxygen. After chemists isolated oxygen for the first time

in the late 1700s, they noticed that it played a role in both burning

and breathing. With that, many scientists declared that breathing was

nothing but slow combustion—a constant burning—inside us.

If slow

fires burned inside us all the time, why couldn’t they suddenly flare

up? Especially in alcoholics, whose very organs were dripping with gin

or rum. (Plus, not to put too fine a point on it, we all pass flammable

gases several times each day.) As for what sets the fires off, perhaps

it was fevers or raging hot tempers.

Lewes,

however, wouldn’t back down. He dismissed Dickens’s sources as

“humorous, but not convincing,” noting that several were more than a

century old. It didn’t help that Dickens enlisted the support of a

celebrity doctor who promoted the fad pseudoscience of phrenology as

well. Lewes also pointed out, rightly, that no factual accounts of

spontaneous combustion had been written by eyewitnesses: They were all

collected secondhand, from a cousin’s friend or a landlord’s

brother-in-law.

Most damning of all, Lewes cited recent

experiments in physiology that revealed how the liver metabolizes

booze, breaking it down for elimination. As a result, the organs of an

alcoholic aren’t soaking in alcohol. Even if they were, science had

shown that the body is roughly 75 percent water, so it couldn’t catch

on fire by itself. Not to mention, it was obvious to doctors by then

that fevers don’t burn nearly hot enough to ignite anything.

Not

surprisingly, Dickens dug in. His relationship with science had always

been ambivalent: He couldn’t deny the marvels that science had wrought,

but he was fundamentally romantic and thought science killed the

imagination and undermined Christian life. He also detested society’s

growing dependence on data and reductionism. Artistically, Dickens

considered the scene with Krook so central to the novel (which involves

a ruinous court case that consumes the lives and fortunes of everyone

involved) that he couldn’t stand it being picked apart. And the more

defensive Dickens got, the more disgusted Lewes became. They bickered

for 10 months, before mutually dropping the matter when the final

installment of

Bleak House appeared in September 1853.

History,

of course, has judged Lewes the winner here: Outside of the tabloids,

no human being has ever spontaneously combusted. In reality,

practically every “spontaneous combustion” case has found the person to

be near a fire source like candles or cigarettes. They likely

accidentally lit themselves on fire, and clothing, fat tissue, methane

gas, and (if it’s built up from alcoholism) acetone kindled the

unfortunate blaze. Still, Lewes and other scientists didn’t understand

as much as they assumed. For instance, they believed that the combustion

of energy inside us took place inside the lungs and not, as we now

know, inside cells themselves.

Dickens’s popularity no doubt

delayed the death of spontaneous combustion in the popular mind. (One

medical text was still discussing claims of spontaneous combustion as

late as 1928.) But Dickens was certainly right about one thing: that in

human affairs, spontaneous combustion does happen. Friendships and

reputations can ignite instantly and leave little in their wake.

Dickens and Lewes eventually patched things up and seemingly never

spoke of the matter again. But for much of 1853 the fires burned

awfully hot.

Most

of the public, anyway. A few readers were outraged by the scene. After

all, scientists had been laboring to debunk old nonsense like

clairvoyance, mesmerism, and the idea that people sometimes burst into

flames. And key discoveries about heat, electricity, and other phenomena

provided strong support for their view, showing that the human body,

far from being otherworldly, was subject to all physical laws of nature.

But the science was still behind. And there were enough mysteries for

old wives’ tales to retain a foothold. This only made both sides more

desperate to prove their case, and within two weeks skeptics began

challenging Dickens in print, inciting one of the strangest

controversies in literary history.

Most

of the public, anyway. A few readers were outraged by the scene. After

all, scientists had been laboring to debunk old nonsense like

clairvoyance, mesmerism, and the idea that people sometimes burst into

flames. And key discoveries about heat, electricity, and other phenomena

provided strong support for their view, showing that the human body,

far from being otherworldly, was subject to all physical laws of nature.

But the science was still behind. And there were enough mysteries for

old wives’ tales to retain a foothold. This only made both sides more

desperate to prove their case, and within two weeks skeptics began

challenging Dickens in print, inciting one of the strangest

controversies in literary history.